Hair dye products are commonly used by both men and women to enhance youth and beauty and to follow fashion trends. As reported in the medical literature, hair dyes and their ingredients are associated with allergic contact dermatitis. A possible association with joint inflammation has also been recognized. There is literature to support that para-phenylenediamine or p-phenylenediamine (PPD), a component of many hair dyes, is proinflammatory and also associated with an increased risk of developing systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). This case illustrates the need to increase awareness about chemicals found in hair dyes and the possible links to inflammatory arthritis and other autoimmune diseases.

Hair dye products are commonly used by both men and women to enhance youth and beauty and to follow fashion trends. As reported in the medical literature, hair dyes and their ingredients are associated with allergic contact dermatitis. A possible association with joint inflammation has also been recognized. There is literature to support that para-phenylenediamine or p-phenylenediamine (PPD), a component of many hair dyes, is proinflammatory and also associated with an increased risk of developing systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). This case illustrates the need to increase awareness about chemicals found in hair dyes and the possible links to inflammatory arthritis and other autoimmune diseases.

Case Presentation

A 50-year-old white man, with a past medical history remarkable for asthma, allergic rhinitis and treated latent tuberculosis, described low back, hand and Achilles tendon pain he’d been experiencing for four months. The pain restricted his recreational activities, including playing guitar and running, but he did get some relief when he took naproxen.

He said he had not experienced psoriasis, skin rash, nail changes, diarrhea, uveitis, urethritis, joint swelling, fever, fatigue or weight loss. A review of systems was otherwise unremarkable.

His sister has a history of psoriatic arthritis.

The physical exam revealed that he had swollen and tender second and third proximal interphalangeal joints and right third metatarsal joint on his right hand, as well as swelling and tenderness in the first interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints on his left hand. He also had right elbow tenderness, with slightly reduced right elbow extension. The range of motion in the rest of his joints was normal. There was no evidence of a skin rash, dactylitis, enthesitis, nail pitting or sacroiliac joint pain.

Lab tests, including those for complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, anti-CCP antibodies, hepatitis B and C, and QuantiFERON-TB gold were unremarkable. However, a rheumatoid factor test was positive at 22 IU/mL (normal: <14 IU/mL).

The patient was hesitant to start on disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) for inflammatory joint pain due to the potential side effects. Thus, the rheumatologist chose to follow him closely to assess disease progression.

Eight months after the initial onset of his symptoms, the patient’s joint pain completely resolved, and he was able to get back to his routine recreational activities. He noticed a correlation between the onset of joint pains and the use of hair dye on his beard. He decided to stop using the hair dye and noticed the joint pain had resolved. He is now able to run and play his guitar.

Discussion

PPD is the most common and most well-known component of hair dyes.1 It was first described by August Hofmann in 1863, and it was formulated at the end of the 19th century for use in hair dyes.2,3 It is favored in hair products due to its long-lasting character and the natural-appearing color imparted to the hair. PPD requires a secondary ingredient, such as a developer or oxidizer, to produce a black color. When exposed to the epidermis or dermis, PPD is oxidized to an allergenic hapten.

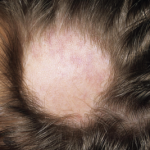

The ingredients in hair dyes are generally thought to have low to moderate acute toxicity, such as allergic contact dermatitis. Contact allergy to PPD can manifest as acute, subacute or chronic dermatitis. Studies involving dermatitis patients show the median prevalence of positive PPD patch test to be 6.2% in North America, 4% in Europe and 4.3% in Asia.4,5 Higher concentrations of PPD are present in darker shades of hair dye products.6 The frequency of induction of contact allergy to PPD by black henna tattooing is estimated to be 2.5% per application. Epicutaneous patch testing is the gold standard test to confirm hair dye contact allergy.

Environmental factors, including microbial agents, vaccines, diet, drug exposure, heavy metals and ultraviolet radiation, are believed to be involved in the pathogenesis of inflammatory arthritis in patients with a genetic susceptibility.7,8 Cigarette smoking is an example of a non-infectious environmental agent associated with the development of rheumatoid arthritis, autoimmune thyroiditis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC).9,10 Silica exposure has been linked to scleroderma, RA, vasculitis and SLE.11 Certain solvents, such as trichloroethylene, mineral spirits and petroleum-based products, have been linked to scleroderma and other connective tissue diseases. Hair dyes have previously been suggested as a possible environmental trigger in the development of autoimmune inflammatory syndromes, including SLE, PBC and RA, but few studies address these compounds specifically.12-15

The development of autoimmune disease following exposure to environmental triggers is postulated to occur through various immunologic mechanisms, such as the alteration of autoantigen structure, altered expression of antigens, stimulatory effects on the immune system, T cell dysregulation, apoptosis-mediated autoimmunity, molecular mimicry and immunological cross-reactivity. These ultimately result in increased production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin 10 (IL-10) and TGF-β, and immune complex formation.16,17

Rubin et al. studied the immune responses in mice repeatedly exposed to PPDs.18 The study revealed increased cellular infiltration after multiple exposures, with the inflammatory response peaking after four weeks. Flow cytometry demonstrated increased proliferation of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the mice.18 A second series of analyses was conducted with hair dyes (as opposed to PPD alone), which produced similar results, with the exception of a higher increase in regulatory T cells (Tregs) than was seen in PPD use alone.18 Thus, hair dye use can induce a proinflammatory immune response, as well as possibly influence the autoantibody profile.

An early case study by Freni-Titulaer et al. indicates a positive association between the use of hair dyes and autoimmune inflammatory syndromes.19 However, a larger study carried out by Petri and Allbritton involving 218 SLE patients from the Hopkins Lupus Cohort found no significant relationship between hair dye use and the development of SLE.20 This study asked the participants to fill out a questionnaire on hair product use.

More recently, Cooper et al. found permanent hair dye use was associated with a small increase in the risk of developing SLE, especially with dark-colored dyes.21 The study examined the association between smoking and hair treatments (e.g., dyes, permanents) and the risk of developing SLE. Two hundred and sixty-five patients were recruited from rheumatology practices, and data were collected by 60-minute, in-person interviews analyzing the experiences that occurred before diagnosis. The study showed a small risk for developing SLE with use of permanent hair dyes (odds ratio [OR] 1.5; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.0–2.2) and with longer duration of use (OR 1.7; 95% CI 1.0–2.7; for six or more years) compared with non-dye users. The study did not show any association with smoking history and risk of developing SLE.

According to a study conducted in Sweden (1980–95), using hair dyes for more than 20 years damaged the immune system, increasing the likelihood of RA developing (exposed cases/referents 17/10; OR 1.9; 95% CI 0.8–4.5).14

In summary, we describe a patient who developed an inflammatory arthritis with concomitant use of hair dye. The timing and history of hair dye exposure was fundamental for the diagnosis. In patients where an association between use of hair dye and inflammatory disease is made, treatment goals include improving symptoms and increasing functional activity. Withdrawal of the causative hair dye was the mainstay treatment for our patient and is essential for all patients where this is suspected. In addition, physical therapy and NSAIDs can be used for the inflammatory joint pain. Anti-rheumatic therapy may be considered if the joint inflammation does not resolve when the offending agent is eliminated. Treatment with a potent topical corticosteroid or short course of oral corticosteroids may be required if there is concomitant skin involvement.

We recommend that manufacturers of hair dye products consider keeping the PPD concentration to the lowest possible amount to achieve the desired results. Restriction to PPD-free hair dyes and vegetable-based hair dye may be the safest solution for those exhibiting PPD sensitization. Hair stylists should be advised to use gloves while applying hair dyes to prevent contact with hands. Reading the ingredient list is imperative, especially if a hypersensitivity or immunologic reaction is suspected.

Conclusion

Efforts have been made to understand the possible link between hair dyes and inflammatory arthritis. Further research is warranted to address the significance of this issue, especially with respect to the safety of hair dye ingredients. We urge rheumatologists to be aware of the link between hair dyes and inflammatory arthritis. Obtaining a detailed history regarding environmental exposures is crucial in patients with inflammatory diseases.

Hrudya Abraham, MD, is a rheumatology fellow in the University of Cincinnati Medical Center Division of Immunology, Allergy and Rheumatology.

Hrudya Abraham, MD, is a rheumatology fellow in the University of Cincinnati Medical Center Division of Immunology, Allergy and Rheumatology.

Eric J. Warm, MD, FACP, is the Richard W. & Sue P. Vilter Professor of Medicine and the program director for internal medicine at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center.

Eric J. Warm, MD, FACP, is the Richard W. & Sue P. Vilter Professor of Medicine and the program director for internal medicine at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center.

Avis Ware, MD, is a professor of medicine and the director of the Rheumatology Clinic in the University of Cincinnati Medical Center Division of Immunology, Allergy and Rheumatology.

Avis Ware, MD, is a professor of medicine and the director of the Rheumatology Clinic in the University of Cincinnati Medical Center Division of Immunology, Allergy and Rheumatology.

References

- Mukkanna KS, Stone NM, Ingram JR. Para-phenylenediamine allergy: current perspectives on diagnosis and management. J Asthma Allergy. 2017;10:9–15. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S90265

- Hefford B. Colour and controversy. Chemistry World. 2012 Oct 2.

- Hofmann AW. Organische Basen. Jahresberichte ueber die Fortschritte der Chemie. [Annual report of progress in chemistry] 1863;3:422. German.

- Thyssen JP, White JM. European Society of Contact Dermatitis. Epidemiological data on consumer allergy to p-phenylenediamine. Contact Dermatitis. 2008 Dec;59(6):327–343.

- Sharma VK, Sethuraman G, Garg T, et al. Patch testing with the Indian standard series in New Delhi. Contact Dermatitis. 2004 Nov–Dec;51(5–6):319–321.

- Vogel TA, Coenraads PJ, Bijkersma LM, et al. p-Phenylenediamine exposure in real life—a case–control study on sensitization rate, mode and elicitation reactions in the northern Netherlands. Contact Dermatitis. 2015 Jun;72(6):355–361.

- D’Cruz D. Autoimmune diseases associated with drugs, chemicals and environmental factors. Toxicol Lett. 2000 Mar 15;112–113:421–432.

- Fournié GJ, Mas M, Cautain B, Savignac M, et al. Induction of autoimmunity through bystander effects. Lessons from immunological disorders induced by heavy metals. J Autoimmun. 2001 May;16(3):319–326.

- Costenbader KH, Karlson EW. Cigarette smoking and autoimmune disease: What can we learn from epidemiology? Lupus. 2006;15(11):737–745.

- Sugiyama D, Nishimura K, Tamaki K, et al. Impact of smoking as a risk factor for developing rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 Jan;69(1):70–81.

- Cooper GS, Wither J, Bernatsky S, et al. Occupational and environmental exposures and risk of systemic lupus erythematosus: Silica, sunlight, solvents. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010 Nov;49(11):2172–2180.

- Smyk D, Rigopoulou EI, Bizzaro N, Bogdanos DP. Hair dyes as risk for autoimmunity: From systemic lupus erythematosus to primary biliary cirrhosis. Auto Immun Highlights. 2012 Jan 13;4(1):1–9.

- Price EJ, Venables PJ. Drug-induced lupus. Drug Saf. 1995 Apr;12(4):283–290.

- Reckner Olsson A, Skogh T, Wingren G. Comorbidity and lifestyle, reproductive factors, and environmental exposures associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001 Oct;60(10):934–939.

- Lundberg I, Alfredsson L, Plato N, et al. Occupation, occupational exposure to chemicals and rheumatological disease. A register based cohort study. Scand J Rheumatol. 1994;23(6):305–310.

- Christen U, Hintermann E, Holdener M, von Herrath MG. Viral triggers for autoimmunity: Is the ‘glass of molecular mimicry’ half full or half empty? J Autoimmun. 2010 Feb;34(1):38–44.

- Alunno A, Bartoloni E, Nocentini G, et al. Role of regulatory T cells in rheumatoid arthritis: Facts and hypothesis. Auto Immun Highlights. 2010 Jul 10;1(1):45–51.

- Rubin IM, Dabelsteen S, Nielsen MM, et al. Repeated exposure to hair dye induces regulatory T cells in mice. Br J Dermatol. 2010 Nov;163(5):992–998.

- Freni-Titulaer LW, Kelley DB, Grow AG, et al. Connective tissue disease in southeastern Georgia: A case-control study of etiologic factors. Am J Epidemiol. 1989 Aug;130(2):404–409.

- Petri M, Allbritton J. Hair product use in systemic lupus erythematosus. A case-control study. Arthritis Rheum. 1992 Jan;35(6):625–629.

- Cooper GS, Dooley MA, Treadwell EL, et al. Smoking and use of hair treatments in relation to risk of developing systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2001 Dec;28(12):2653–2656.