A 39-year-old woman presented at the emergency department with three weeks of progressive, constant and pulsatile right-sided headache. She said her headache was worse in the morning and when she would bend forward. She reported associated nausea and vomiting.

On initial assessment, she did not have any focal neurological deficits. Her medical history was significant for tobacco use, alcohol abuse, depression and recent diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. Behçet’s was diagnosed on the basis of many years of recurrent oral ulcers, one year of recurrent genital ulcers, diffuse arthralgia, positive pathergy, history suggestive of prior iritis and pustular skin eruption with an otherwise negative rheumatologic workup. At the time of presentation, she was not on any treatment for Behçet’s disease due to financial limitations.

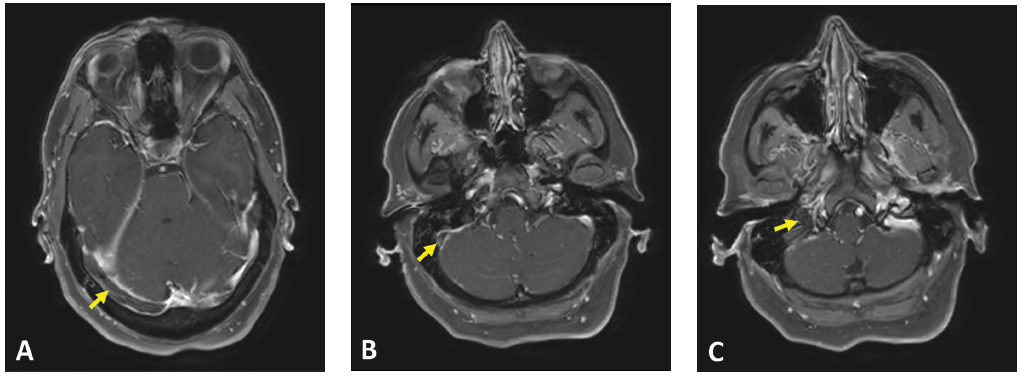

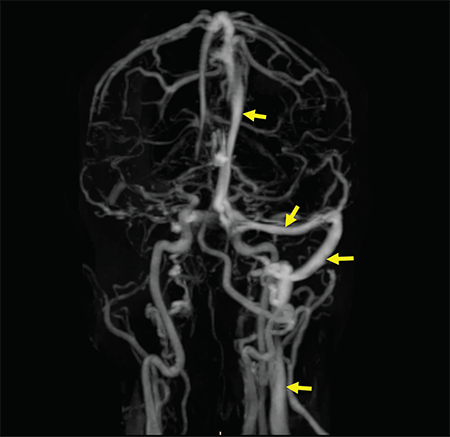

In the emergency department, she was promptly evaluated with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance venography (MRV), and was found to have extensive sinus thrombosis involving the right internal jugular vein, right sigmoid sinus, right transverse sinus and right superior sagittal sinus (see Figures 1 and 2). She did not have any findings suggestive of infarction or hemorrhage.

Her ophthalmologic evaluation did not show any evidence of subclinical uveitis or optic neuritis. The findings of cerebral venous sinus thrombi (CVST) were attributed to Behçet’s disease, and a hypercoagulable workup, including factor V Leiden, prothrombin 20210 mutation and antiphospholipid antibodies, was later unrevealing.

Treatment with anticoagulation and immunosuppression was initiated. She received high-dose prednisone (1 mg/kg) and was started on azathioprine (1 mg/kg; 50 mg twice daily), with resolution of her headache within the first two weeks of treatment. Prednisone was gradually tapered over 12 months without signs or symptoms concerning for relapse. For anticoagulation, she initially received unfractionated heparin and was then transitioned to warfarin to complete a total of eight months of treatment. The duration of anticoagulation was determined on the basis of resolution of the thrombi on subsequent imaging at three and six months.

(click for larger image) Figure 1: Axial T1 contrast MR image showing non-enhancement within the (A) right transverse sinus, (B) right sigmoid sinus and (C) right internal jugular vein. Associated dural enhancement is visualized around the transverse sinus (A) and sigmoid sinus (B).

Behçet Disease

Behçet’s disease was first described by Hulusi Behçet, a Turkish dermatologist, in 1937 and was defined as a syndrome of recurrent oral aphthous ulcers, genital ulcers and uveitis.1 It’s classified as a variable vessel vasculitis (can affect vessels of any size and type), affecting both arteries and veins.2 The definition of Behçet’s disease has been refined over the years and the most widely used diagnostic criteria today are based on the International Study Group Diagnostic Criteria published in 1990. These include recurrent oral ulcerations of at least three incidents in a 12-month period, in addition to two other manifestations of recurrent genital ulcers, eye lesions, skin lesions or a positive pathergy test.1,3

In 2014, classification criteria were revised by the International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease (ICBD), which increased their sensitivity by including neurological and vascular manifestations in addition to oral and genital ulcerations. A score of 4 or more points is estimated to have 93.9% sensitivity and 92.1% specificity.4

When interviewing a patient with Behçet’s disease & new-onset headache, reports of morning headache, a positional component, worsening with Valsalva & refractoriness to therapy should prompt a cerebral venous sinus thrombi workup.

Neuro-Behçet Disease

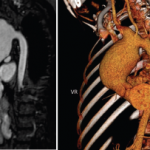

Figure 2: A contrast-enhanced MRV shows a filling defect in the right internal jugular vein, right sigmoid sinus, right transverse sinus and superior sagittal sinus. Normal enhancement of the respective structures is visualized on the left side (arrow).

As a multisystem inflammatory disease, Behçet’s disease can affect any organ or system in the body, including the nervous system. Neurological manifestations in Behçet’s disease are generally divided into parenchymal (intra-axial) and non-parenchymal (extra-axial). A diagnosis of neuro-Behçet disease is considered in patients who fulfill Behçet’s disease diagnostic criteria, do not have an alternative explanation for neurological symptoms and have supportive objective evidence of abnormal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis and/or abnormal MRI imaging.5

The most common presentation of parenchymal neuro-Behçet’s disease is a brainstem syndrome, which can present with ophthalmoparesis, dysarthria, weakness and ataxia. Headache is commonly reported in meningoencephalopathy. Less commonly, patients can present with cerebral hemisphere involvement, mass-like lesions on MRI, seizures and cognitive-behavioral changes.5,6

Non-parenchymal neuro-Behçet’s disease mainly involves CVST. CVST presents with signs of elevated intracranial pressure, namely headache, mental status changes, papilledema and cranial nerve VI palsy. CVST accounts for 10–20% of neuro-Behçet’s disease and is present in 5–6% of patients with Behçet’s disease.7 Although severity and progression of symptoms vary according to size and site of thrombosis, CVST usually presents in a subacute and progressive manner, rather than acute fulminant symptoms with rapid mental status change and seizures. CVST tends to occur earlier in the course of disease compared with parenchymal neuro-Behçet’s disease and occurs more commonly in males. Thrombosis can occur in any number of cerebral sinuses, but is most commonly reported in the superior sagittal and transverse sinus.

Headache in Behçet Disease

Headache is one of the most common symptoms in patients with Behçet’s disease, regardless of neurologic involvement. Prevalence of headache is reported between 44 and 80%. Depending on the population, the headaches are attributable to migraine or tension, rather than neuro-Behcet’s.7

In a cohort of more than 200 patients with Behçet’s disease and headaches, parenchymal and non-parenchymal neurologic involvement was seen in 5.2% and uveal inflammation was seen in 3.9% of the patients.5,6 However, in patients with confirmed neuro-Behçet’s disease, headache remains the most commonly reported presentation.

Determination of initial investigation and management of headache in Behçet’s disease patients relies heavily on obtaining a thorough history and neurological examination. Any reported complaint of headache warrants obtaining a detailed history that includes onset, duration, quality, and alleviating and exacerbating factors. Additionally, concurrent relapse of other features of Behçet’s disease, such as oral or genital ulceration, should heighten suspicion for neuro-Behçet’s disease in a patient presenting with headache. Missed and untreated CVST can lead to venous congestion, cerebral edema and, eventually, brain herniation and death.9

Investigations

In a patient with Behçet’s disease who presents with headache, if CVST is suspected, neuroimaging evaluation with MRI and MRV should be promptly performed to assess for venous sinus and deep vein occlusion, and to rule out other causes of headache, such as mass or hemorrhage.

Lumbar puncture should also be considered to aid with excluding other causes of severe headache, such as infection. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis can be normal, but if abnormal, the most notable findings are elevated opening pressure and lymphocytic predominant elevated cell count. 5,6

Once CVST is confirmed, screening for vascular disease at an extracranial site is recommended by current guidelines.10.11 Many patients with this complication present to tertiary medical centers with a known diagnosis of CVST and on anticoagulation, so it’s not always feasible to perform lumbar puncture.

Although Behçet’s disease is a predisposing factor for development of CVST, other pro-thrombotic factors can often be found in patients with Behçet’s disease. A study of 64 patients with Behçet’s disease and CVST found at least one other associated pro-

thrombotic factor in 31% of the cases, including methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene mutation, hyperhomocysteinemia, protein C deficiency and factor V Leiden mutation. Other environmental pro-thrombotic risk factors, such as smoking status and use of estrogen-containing contraceptive methods, were also reported in 34–36% of cases of CVST in the same study.12

Treatment

The general therapeutic approach in treating Behçet’s disease-associated CVST is to optimize immunosuppression, given that the underlying mechanism is inflammation of the vessel wall.10 This is commonly achieved with high-dose glucocorticoids, pulse dose or 1 mg/kg, followed by a slow taper over several months. Other immunosuppressive therapies used concomitantly as steroid-sparing medications include cyclophosphamide, azathioprine and TNF inhibitors for severe or refractory cases.10,12,13

The EULAR guidelines for management of Behçet’s disease recommend against the use of cyclosporin-A, due to available data from observational studies that suggest cyclosporin-A increases the risk of nervous system involvement in patients with Behçet’s disease due to its neurotoxic effects.10,11 Immunosuppressive therapy has been shown to significantly reduce the risk of CVST recurrence.13,14

Due to a lack of evidence from clinical trials and presumed increased risk of bleeding associated with anticoagulation, no clear consensus exists on the use and duration of anticoagulation for thrombosis in Behçet’s disease.10,15 That said, most experts in the U.S. would likely recommend anticoagulation until the thrombosis resolves, as long as there are no contraindications.

In a retrospective study of 21 Behçet’s disease patients with CVST, except for one patient with hemoptysis and subarachnoid hemorrhage, all received long-term anticoagulation without any adverse effects.13 Similarly, in a prospective, placebo-controlled trial of 64 patients with CVST, over 90% received long-term anticoagulation without severe hemorrhagic complications, and the outcomes of those treated with anticoagulation were not worse than those treated with immunosuppressive therapy.12

Take-Home Messages

- Neuro-Behçet’s disease has protean manifestations, and a high degree of suspicion is needed for prompt diagnosis.

- Headache is a common symptom in Behçet’s disease and often a presenting symptom of neuro-Behçet’s disease.

- When interviewing a patient with Behçet’s disease and new-onset headache, reports of morning headache, a positional component, worsening with Valsalva and refractoriness to therapy should prompt an evaluation for CVST.

- Consider a workup for a hypercoagulable state in patients with Behçet’s disease and CVST.

- Treat with high-dose steroids and immunosuppression, and consider anticoagulation, if not contraindicated, based on the severity of the thrombotic event.

A multidisciplinary approach, including neurology, vascular medicine, hematology and rheumatology, is key in therapeutic decision making. Current guidelines seem flexible and based on expert opinion.

Javaneh Lyons, MD, MSc, is a second-year fellow in adult rheumatology at the University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington.

Javaneh Lyons, MD, MSc, is a second-year fellow in adult rheumatology at the University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington.

Alana Nevares, MD, is an assistant professor in the Division of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology, Robert Larner, MD, College of Medicine, at the University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington.

Alana Nevares, MD, is an assistant professor in the Division of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology, Robert Larner, MD, College of Medicine, at the University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington.

Acknowledgment

The authors extend special thanks to Scott Legunn, MD, and Maria Sayeed, MD, who were the treating rheumatologists at the time of disease onset and established a prompt diagnosis.

References

- Akman-Demir G, Saip S, Siva A. Behçet’s disease. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2011 Jun;13(3):290–310.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Jan;65(1):1–11.

- Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease. Lancet. 1990 May 5;335(8697):1078–1080.

- Davatchi F, Assaad-Khalil S, Calamia KT, et al for the International Team for the Revision of the International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease (ITR-ICBD). The International Criteria for Behcet’s Disease (ICBD): A collaborative study of 27 countries on the sensitivity and specificity of the new criteria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014 Mar;28(3):338–347.

- Saip S, Akman-Demir G, Siva A. Neuro-Behçet syndrome. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;121:1703–1723.

- Al-Araji A, Kidd DP. Neuro-Behçet’s disease: Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and management. Lancet Neurol. 2009 Feb;8(2):192–204.

- Saip S, Siva A, Altintas A, et al. Headache in Behçet’s syndrome. Headache. 2005 Jul–Aug;45(7):911–919.

- Aguiar de Sousa D, Mestre T, Ferro JM. Cerebral venous thrombosis in Behçet’s disease: A systematic review. J Neurol. 2011 May;258(5):719–727.

- Luo Y, Tian X, Wang X. Diagnosis and treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis: A review. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018 Jan 30;10:2.

- Hatemi G, Silman A, Bang D, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of Behçet disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Dec;67(12):1656–1662.

- Hatemi G, Christensen R, Bang D, et al. 2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of Behçet’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Jun;77(6):808–818.

- Saadoun D, Wechsler B, Resche-Rigon M, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis in Behçet’s disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Apr;61(4):518–526.

- Shi J, Huang X, Li G, et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in Behçet’s disease: A retrospective case-control study. Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Jan;37(1):51–57.

- Desbois AC, Wechsler B, Resche-Rigon M, et al. Immunosuppressants reduce venous thrombosis relapse in Behçet’s disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2012 Aug;64(8):2753–2760.

- Tayer-Shifman OE, Seyahi E, Nowatzky J, Ben-Chetrit E. Major vessel thrombosis in Behçet’s disease: The dilemma of anticoagulant therapy—the approach of rheumatologists from different countries. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012 Sep–Oct;30(5):735–740.