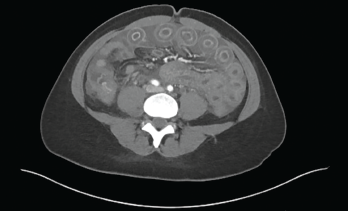

Figure 1: Computed Tomography of the Abdomen

Our patient was a 33-year-old, 5’2″ Asian woman with a past medical history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The diagnosis was based on serologies positive for anti-nuclear antibodies (ANAs), as well as antibodies to Sm, RNP and SSA. Her illness included neuropsychiatric and cutaneous involvement. She also had a diagnosis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

She presented with two weeks of abdominal bloating and one week of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and non-bloody diarrhea. Her symptoms began two weeks before, with abdominal fullness and bloating, which progressed to acute-onset, diffuse, intermittent, cramping abdominal pain associated with non-bloody emesis and multiple episodes of non-bloody, watery diarrhea. She had not been able to tolerate oral intake for the past few days. She denied fevers, chills, sick contacts or recent travel, but said a sweet potato casserole she ate may have been “bad.”

One week prior to admission, she was seen in student health and was given intravenous fluids and antiemetics. A few days prior to admission, she presented to the emergency department for persistent symptoms. An abdominal ultrasound done in the emergency department was unremarkable, a pregnancy test was negative, and enteric stool pathogen testing was negative. She improved after receiving intravenous fluids and antiemetics and was again sent home.

The patient felt better for one or two days and was able to eat and drink, but then her symptoms returned—this time with more severe abdominal pain and bloating—and she returned to the emergency department.

On further questioning, she reported a similar episode occurred about 11 months before. That episode lasted for a few days and resolved after she was administered intravenous fluids at student health.

Lupus History

Figure 2: Radiograph of the Chest

Our patient was first diagnosed with SLE in 2014. She had acute cutaneous lupus, with biopsy-proven interface dermatitis (i.e., a pattern of skin reaction characterized by an inflammatory infiltrate that appears to obscure the dermo-epidermal junction when observed at low-power examination and referred to as lichenoid tissue reaction) and was initiated on 200 mg of hydroxychloroquine twice a day.

In 2015, she developed neuropsychiatric symptoms—seizures with an elevated immunoglobulin G (IgG) index on her cerebrospinal fluid analysis—as well as oral ulcers and alopecia. Serologies at that time were remarkable for an ANA of 1:1280 in a speckled pattern, anti-Sm, anti-RNP and anti-SSA antibodies, low complements and leukopenia.

She was treated with 1,000 mg of intravenous methylprednisolone daily for three days. Her treatment also included 1,500 mg of mycophenolate mofetil twice a day, 200 mg of hydroxychloroquine twice a day and a slow taper of prednisone.

She self-discontinued all of her medications toward the later part of 2015 due to what she described as medication side effects and a concern for toxicity.

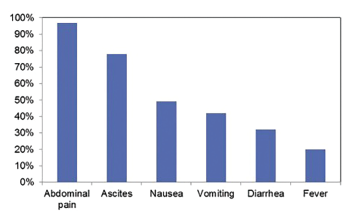

Figure 3: Incidence of Symptoms at Presentation with Lupus Enteritis3

Since 2015 she has had intermittent flares, attributed to SLE, with rashes on her hands and joint pain, predominantly in her hands. Flares tended to be cyclic and related to her menses. She self-managed her symptoms with stress reduction and homeopathic modalities. She had no recent hospitalizations or steroid tapers. She did not think her current symptoms were typical of an SLE flare, and she was taking no medications at the time of presentation.

Review of Systems

The patient had chronic hair loss, difficulty taking a deep breath due to abdominal pain, esophageal reflux, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, anorexia, rash on her hands and an oral ulcer. She denied fevers, chills, weight loss, joint pain or swelling, chest pain, headaches, vision changes, dyspnea, dysuria, hematuria, weakness, leg swelling, seizures, blood clots, miscarriages, recent travel, sick contacts, a history of inflammatory bowel disease or Raynaud’s phenomenon.

At presentation, she was not sexually active and denied sexually transmitted illnesses in the past and no recent exposures. She denied tobacco, alcohol and drug use.

Physical exam: On examination, the patient’s blood pressure was 114/88. Her heart rate was 100 beats per minute, and her respiratory rate was 20 breaths per minute, with an SpO2 of 99% on room air. Her temperature was 36.5ºC (97.7ºF). She weighed 59.6 kg (131 lbs.) and had a BMI of 24.04 kg/m².

General: The patient was alert, awake and oriented to person, place and time. She could carry out normal conversation. She appeared uncomfortable lying in bed. The examination of her head, eyes, ears, nose and throat (HEENT) revealed moist mucous membranes and oral ulceration in the posterior pharynx on her left side. Her neck was supple, without lymphadenopathy, and she demonstrated adequate range of motion. Her lungs were both clear to auscultation. She had no wheezes or crackles. She had a regular heart rate and rhythm, and normal S1 and S2 heart sounds, with no murmurs, rubs or gallops.

She had hypoactive bowel sounds. Her abdomen was soft, distended and diffusely tender, including rebound tenderness. She had no organomegaly.

Her extremities were well perfused, with no edema. Her sensation was grossly intact. No tenderness or swelling was appreciated in any joints of her hands, wrists, elbows, shoulders, hips, knees, ankles or feet.

She had mild hair thinning, no scarring alopecia and no malar rash. Her hands were cool to touch, and she had small, blanching macules on her palmar surface and the sides of her fingers. She had no other rashes.

Blood tests: CBC: Her white blood cell count (WBC) was 10,500 cells/µl, her hemoglobin was 13.9 g/dL, her platelets were 255,000 cells/µl, her absolute neutrophil count was 9,100 cells/µl, and the absolute lymphocyte count was 500 cells/µl. Her liver function tests, creatinine kinase and a lipase were normal. Her albumin was low, at 2.5 g/dL (normal range, 3.9–5.5 g/dL). Her creatinine was 0.97 mg/dL and rose to 1.38 mg/dL on a subsequent check. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 15 mm/hr, and her C-reactive protein was 2.7 mg/dL (upper limit of normal 0.8 mg/dL). A urinalysis showed a specific gravity of 1.06, small blood and 30 mg/dL protein. Urine microscopy showed 2–5 red blood cells. Clostridium difficile testing was negative. Her thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level was 16.2 uIU/mL with a normal free T4 (1.34 uIU/mL). Blood cultures and tests for enteric pathogens were sent.

Imaging: An abdominal ultrasound taken during the patient’s emergency department visit three days earlier showed mild prominence of the right renal collecting system, without visualized obstruction. No other acute sonographic findings of the abdomen were revealed.

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis revealed diffuse gastroenteritis, with wall thickening involving the stomach, duodenum, small bowel and colon (see Figure 1). Mucosal hyperenhancement demonstrated a target-like appearance. Mildly complex ascites and extensive mesenteric fat stranding were apparent. Mild wall thickening of the peritoneum raised the possibility of concomitant peritonitis. The CT showed patent abdominal vasculature, no pneumoperitoneum, pneumobilia or portal venous gas. There was mild, bilateral hydroureteronephrosis, with subtle enhancement of the ureteral urothelium. An X-ray of the chest (see Fig. 2) revealed new, small, bilateral pleural effusions and low lung volumes with mild bibasilar atelectasis.

Diagnosis

At this point our differential diagnoses included mesenteric/portal vein thrombosis, inflammatory bowel disease, small bowel ischemia, lupus/autoimmune enteritis, vasculitis or malignancy.

A gastroenterologist was consulted, and an abdominal ultrasound with duplex was recommended to look for Budd-Chiari syndrome, an angiogram to evaluate the mesenteric vasculature and a push enteroscopy with biopsies of the stomach and small bowel.

Paracentesis revealed a total WBC count of 498 cells/µl: 81% monocytes, 12% lymphocytes, 6% neutrophils and 1% eosinophils. The red blood cell count was 454 cells/µl, glucose 42 mg/dL, lactate dehydrogenase 169 U/L and serum-ascites albumin gradient was <1.1 g/dL. Cultures for bacteria, acid fast bacilli and fungus were negative. Cytology revealed reactive mesothelial cells and chronic inflammation, with no malignancy.

An abdominal ultrasound with duplex revealed a patent main portal vein and middle hepatic vein, with appropriate direction of flow and a moderate volume of abdominopelvic ascites. A right pleural effusion was partially visualized. The trace, right hydroureteronephrosis had improved from the prior exam.

Stool studies were negative. Her anti-dsDNA antibodies were 594 IU/mL (reference range: 0–99 IU/mL), C3 was 35 mg/dL (lower limit of normal: 88 mg/dL) and C4 was 7 mg/dL (lower limit of normal: 16 mg/dL).

A diagnosis of lupus enteritis was made, and our patient was treated with 1,000 mg of intravenous, pulse-dose methylprednisolone per day for presumed lupus enteritis and then intravenous methylprednisolone taper. With this therapy she improved clinically. She was then initiated on mycophenolate mofetil with a slow up-titration plan at discharge and a plan to start hydroxychloroquine in the outpatient setting.

Abdominal Pain in SLE

The incidence of abdominal pain in patients with SLE ranges from 8–40%.1 Common triggers are infections and medication side effects. Symptoms are often masked by treatment with glucocorticoids and/or immunosuppressive medications, which can lead to a delay in diagnosis.

Autopsy studies have shown peritonitis in 60–70% of patients with SLE, but clinically, it is described in only 10% of cases.2

Mortality among SLE patients with acute abdominal pain is 11%.2

When evaluating patients, considerations must be given to SLE-related causes, side effects related to medications (e.g., NSAIDs, steroids, hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine) and non-SLE-related causes (e.g., if ascites is present, rule out infection with paracentesis). Table 1 lists the most common causes of acute abdominal pain in SLE patients. Table 2, from a review article by Brewer and Kamen, shows the anatomic distribution of GI involvement among patients with SLE.2

Table 1: Leading Causes of Acute Abdominal Pain in SLE Patients3

| SLE Related | Non-SLE Related |

|---|---|

| Lupus enteritis | Appendicitis |

| Pancreatitis | Lithiasic cholecystitis |

| Pseudo-obstruction | Peptic ulcer |

| Acalculous cholecystitis | Acute pancreatitis |

| Mesenteric thrombosis | Retroperitoneal hematoma |

| Hepatic thrombosis | Ovarian pathology |

| Medications (NSAIDs, MMF, steroids, HCQ …) | Diverticulitis |

| Colon perforation (vasculitis) | Adhesions, intestinal occlusion |

| Infectious enteritis | |

| Pyelonephritis | |

| CMV colitis |

Key: NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; MMF: mycophenolate mofetil; HCQ: hydroxychloroquine.

Table 2: Anatomic Distribution of GI Involvement among Patients with SLE2

| Organ | Involvement |

|---|---|

| Mouth/pharynx | Oral ulcers |

| Esophagus | Dysphagia Esophageal dysmotility Gastric reflux Bullous epidermolysis Ulcerative esophagitis |

| Stomach | Peptic ulcer disease Gastric enteritis Dyspepsia |

| Pancreas | Acute pancreatitis |

| Liver | Hepatomegaly Type 1 autoimmune hepatitis Steatosis Nodular regenerative hyperplasia |

| Gallbladder | Primary sclerosing cholangitis Autoimmune cholangiopathy Acute acalculous cholangitis |

| Small Intestine | Celiac disease Mesenteric vasculitis Protein-losing enteropathy Cytomegalovirus enteritis Intestinal pseudo-obstruction |

| Colon | Crohn’s disease Bowel perforation Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis Benign pneumoperitoneum |

| Rectum, anus | Ulcerations |

| Other | Appendicitis Primary lupus peritonitis Splenomegaly Ascites |

Lupus Enteritis

According to the BILAG 2004 definition, lupus enteritis is either vasculitis or inflammation of the small bowel with supportive imaging and/or biopsy findings.4 It may also be called mesenteric arteritis, intestinal vasculitis, enteric vasculitis, mesenteric vasculitis, lupus peritonitis or abdominal serositis.

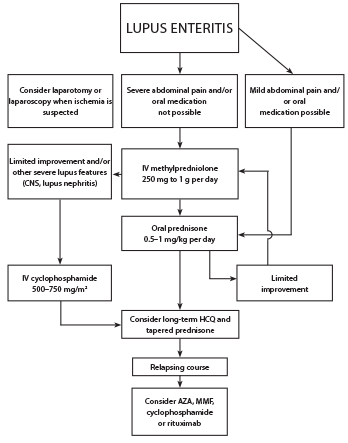

Figure 4: Proposed Treatment Algorithm for SLE Patients with Lupus Enteritis3

Although the pathogenesis of lupus enteritis remains unknown, it has been reported that immune complex-mediated visceral vasculitis may result in bowel wall and mucosal edema.5 The most common clinical manifestations include abdominal pain, ascites, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and fever (see Figure 3,).3

Lab findings in lupus enteritis include anemia (52%), leukocytopenia and/or lymphocytopenia (40%), thrombocytopenia (21%) and hypocomplementemia (88%).3

A retrospective study by Koo et al. found C4 was significantly lower in patients with lupus enteritis.1

A retrospective study and systematic literature review by Janssens et al. found the following lab abnormalities in patients with lupus enteritis: ANA (92%), anti-dsDNA (74%), anti-RNP (28%), anti-SSA (26%) and anti-Sm (24%) antibodies, proteinuria >0.5 g/24h (47%), positive antiphospholipid antibodies (30%). Seven patients in this study met criteria for antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.3

In the same review, the authors found the most common radiographic findings were bowel wall edema (91%); double halo or target sign (71%); dilation of bowel lumen (24%); ascites (78%); mesenteric abnormalities (71%), including engorgement of mesenteric vessels; and increased number of viable vessels (comb sign).3

Table 3 shows the frequency of CT findings in SLE patients with undifferentiated acute abdominal pain.6 The jejunum and ileum are more frequently involved, followed by the colon, duodenum and rectum. Of the cases identified in this review, 15% had endoscopy with normal macroscopic findings in 60%.3 Endoscopic biopsy is of low yield. Therefore, lupus enteritis is generally a diagnosis of exclusion.

Table 3: CT Findings of SLE Patients with Undifferentiated Acute Abdominal Pain6

| CT Findings | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Engorgement of mesenteric vessels | 82 |

| Ascites | 77 |

| Bowel wall thickening | 74 |

| Dilation of intestinal segments (5–13 mm) | 74 |

| Comb sign (engorged mesenteric vessels) | 69 |

| Target sign (bowel wall thickening and enhancement) | 66 |

| Retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy | 61.5 |

| Pleural effusion | 33 |

| Splenomegaly | 33 |

| Hepatomegaly | 25.6 |

| Peritoneal enhancement | 23 |

| Hydronephrosis | 23 |

| Lupus nephritis | 23 |

| Lupus cystitis | 15 |

| Pancreatitis | 10 |

| Venous thrombosis | 10 |

| Splenic infarction | 5 |

| Pneumatosis intestinalis | 2.5 |

| Liver abscess | 2.5 |

Treatment

Corticosteroids are the initial treatment for all patients, with an average duration of four days (range 1–34 days).3 Cyclophosphamide can be considered, especially if there is other severe organ involvement (see Figure 4). Maintenance therapy typically includes hydroxychloroquine, mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine. Most patients have relief of symptoms in less than one week, and recurrence occurs in 23% of patients.3

Dr. Purcell

Emily Purcell, MD, is a second-year rheumatology fellow in the Division of Rheumatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Colin Ligon, MD, MHS, is a rheumatologist at Bon Secours Rheumatology Center, Henrico, Va.

Dr. Derk

Chris T. Derk, MD, MS, is a professor of clinical medicine in the Division of Rheumatology, University of Pennsylvania.

References

- Koo BS, Hong S, Kim YJ, Kim YG, Lee CK, Yoo B. Lupus enteritis: Clinical characteristics and predictive factors for recurrence. Lupus. 2015;24(6):628–632.

- Brewer BN, Kamen DL. Gastrointestinal and Hepatic Disease in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2018; 44(1):165–175.

- Janssens P, Arnaud L, Galicier L, et al. Lupus enteritis: From clinical findings to therapeutic management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013; 8(1):1–10.

- Isenberg DA, Rahman A, Allen E, et al. BILAG 2004. Development and initial validation of an updated version of the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group’s disease activity index for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology. 2005;44(7):902–906.

- Belmont HM, Abramson SB, Lie JT. Pathology and pathogenesis of vascular injury in systemic lupus erythematosus interactions of inflammatory cells and activated endothelium. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39(1):9–22.

- Goh YP, Naidoo P, Ngian GS. Imaging of systemic lupus erythematosus. Part II: Gastrointestinal, renal, and musculoskeletal manifestations. Clin Radiol. 2013;68(2):192–202.

Read a letter to the editor about this article received in March 2021.