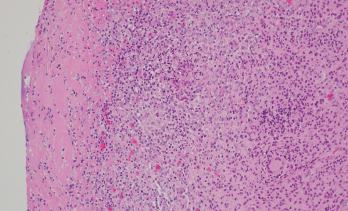

Figure 2. Synovium with granulomatous inflammation consisting of aggregates of histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells, with surrounding lymphocytes and plasma cells. Sections contain no identifiable organisms or crystal deposition. (GMS and AFB immunohistochemical stains were negative.) H&E, 100x.

Source: Picture and description by Mary Hansen Smith MD, University of Arizona, Department of Pathology.

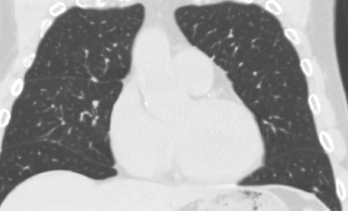

Rifampin was added to his antibiotic regimen. Further evaluation included a high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the chest, which demonstrated sub-centimeter scattered nodules (see Figure 3). Given the nodularity, a diagnosis of disseminated MAC

was established.

The patient’s neurosarcoidosis initially remained in remission, but two years later, he developed a cervical cord lesion. The patient was started back on infliximab monotherapy while continuing to receive treatment with azithromycin, ethambutol and rifampin.

After three doses of infliximab, the patient developed increasing spasticity in the bilateral lower extremities, decreased ability to move his legs and weakness of the right arm. The patient was transitioned from infliximab to rituximab.1 The patient received four weekly doses of 375 mg/m2 of rituximab without discernable benefit. Later, he received radiation to the cervical spine for refractory neurosarcoidosis, but continued to experience a decline in strength.

The patient then started treatment with 300 mg of IV ocrelizumab and 250 mg of IV methylprednisolone. He was continued on triple therapy (i.e., azithromycin, ethambutol and rifampin) to prevent recurrence. The patient continues to follow up with his pulmonologist and neurologist, who are monitoring his response to therapy.

Discussion

Individuals being treated with immunosuppressive agents are more susceptible to fungal and mycobacterial infections. The currently available evidence suggests an increased risk of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection with the use of TNFi’s.2,3 However, the occurrence of non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections with the use of biologics is not well established.

In a case-control study, of 30,772 patients receiving a TNFi, 158 (0.51%) developed targeted fungal and/or mycobacterial infections. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections were identified in 11% of these patients. The study also looked at the odds ratio for patients taking different TNFi’s compared with etanercept to evaluate how likely a patient would be treated for a fungal or mycobacterial infection. For adalimumab vs. etanercept, the odds ratio was 1.05 (0.69–1.62), infliximab vs. etanercept 1.08 (0.66–1.77), and for certolizumab vs. etanercept 0.78 (0.07–8.21). Thus, the study did not see a statistically significant difference between different TNFi’s when compared to etanercept.4

Figure 3. High-resolution computed tomography of the chest demonstrated sub-centimeter, scattered nodularity consistent with disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex.

A retrospective cohort study involving 42,180 rheumatoid arthritis patients suggested the occurrence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis varied with different biologic therapies. The hazard ratio for adalimumab was 1.52 (1.18–1.96), etanercept 1.16 (0.9–1.41) and rituximab 0.08 (0.02–0.31) using conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs-exposed patients as a reference group.5

Another retrospective cohort study involving 951 patients evaluated the occurrence of tuberculosis in RA patients on biologics. The findings suggested a higher Mycobacterium tuberculosis risk for patients receiving etanercept and adalimumab, but not for those receiving golimumab, abatacept, tocilizumab or tofacitinib.6

A retrospective study was conducted to identify the occurrence of non-tuberculous mycobacterial and tuberculosis cases among 8,418 patients with inflammatory diseases who received anti-TNF therapy. The occurrence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial disease was found to be fivefold higher in those receiving a TNFi than in those not receiving a TNFi and tenfold more elevated than in the general population. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial cases occurred more frequently among patients taking a TNFi, and interestingly, these patients were more likely to have chronic lung disease and gastroesophageal reflux disease.7