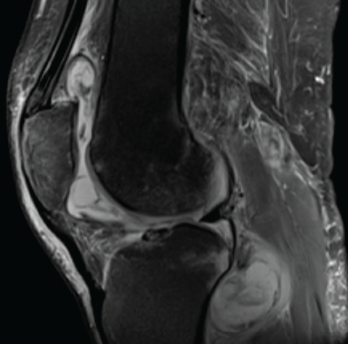

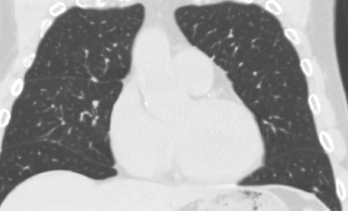

Figure 1. Magnetic resonance imaging of the patient’s left knee shows joint effusion, synovial thickening, and periarticular muscle and soft tissue edema.

Tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors (TNFi’s) have emerged as an integral part of therapeutic strategies for several rheumatic diseases. TNF-α is a pro-inflammatory cytokine implicated in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), seronegative spondyloarthropathies and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It also plays a central role in the immune response to mycobacterial infection.

Many biologic agents, particularly TNFi’s, are associated with an increased risk of tuberculosis; however, the risk of non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections among patients treated with a TNFi has not been studied extensively.

We present this report on a patient with sarcoidosis receiving TNFi therapy who developed a disseminated non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection.

Case History

A 69-year-old man presented to the clinic with symptoms of progressively worsening left knee pain, stiffness and swelling over six months. He was unable to bear weight on the affected leg and was wheelchair bound. He had previously been diagnosed with both neurosarcoidosis and osteoarthritis. He had initially been treated with glucocorticoid monotherapy. Because he deteriorated clinically, 400 mg of intravenous (IV) infliximab every six weeks and 500 mg of mycophenolate mofetil twice a day orally were added to his medical regimen.

His knee had initially been evaluated by his primary care provider; plain radiographs of the knees demonstrated osteoarthritis. Subsequently, he was referred to a sports medicine specialist and an orthopedic surgeon for further evaluation. Oral analgesics, intra-articular steroid injection and physical therapy provided him with no relief, and he was referred to our division for further evaluation.

In our clinic, he was afebrile; his blood pressure was 152/82 mmHg, and his heart rate was 66 bpm. His left knee was swollen, and both passive and active movements were limited by pain.

Laboratory tests on his initial presentation demonstrated leukocytosis; his white blood cell count was 13,200/uL with 86% neutrophils. His complete metabolic panel and urinalysis were unremarkable. Rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated protein antibodies and anti-double stranded DNA antibodies were not detected on immunological studies. Tests for Borrelia and Coccidioides IgG and IgM antibodies were negative.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left knee joint revealed a moderate joint effusion with diffuse synovial thickening, and periarticular muscle and soft tissue edema (see Figure 1, above).

Synovial fluid aspirate demonstrated 8,935 nucleated cells (70% mononuclear) with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare growth in modified Middlebrook 7H9 broth, a liquid growth medium used to culture Mycobacterium.

Infliximab was stopped, and the patient was treated with ethambutol and azithromycin.

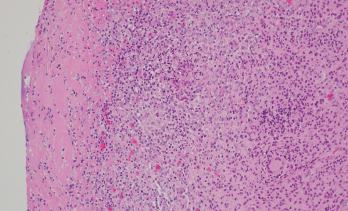

Over the next month, the patient noticed low-grade fever, malaise, night sweats and unintentional weight loss of 10 lbs. He underwent open synovectomy of the left knee. The synovial tissue demonstrated an active granulomatous synovitis (see Figure 2, and synovial cultures grew Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC).

Figure 2. Synovium with granulomatous inflammation consisting of aggregates of histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells, with surrounding lymphocytes and plasma cells. Sections contain no identifiable organisms or crystal deposition. (GMS and AFB immunohistochemical stains were negative.) H&E, 100x.

Source: Picture and description by Mary Hansen Smith MD, University of Arizona, Department of Pathology.

Rifampin was added to his antibiotic regimen. Further evaluation included a high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the chest, which demonstrated sub-centimeter scattered nodules (see Figure 3). Given the nodularity, a diagnosis of disseminated MAC

was established.

The patient’s neurosarcoidosis initially remained in remission, but two years later, he developed a cervical cord lesion. The patient was started back on infliximab monotherapy while continuing to receive treatment with azithromycin, ethambutol and rifampin.

After three doses of infliximab, the patient developed increasing spasticity in the bilateral lower extremities, decreased ability to move his legs and weakness of the right arm. The patient was transitioned from infliximab to rituximab.1 The patient received four weekly doses of 375 mg/m2 of rituximab without discernable benefit. Later, he received radiation to the cervical spine for refractory neurosarcoidosis, but continued to experience a decline in strength.

The patient then started treatment with 300 mg of IV ocrelizumab and 250 mg of IV methylprednisolone. He was continued on triple therapy (i.e., azithromycin, ethambutol and rifampin) to prevent recurrence. The patient continues to follow up with his pulmonologist and neurologist, who are monitoring his response to therapy.

Discussion

Individuals being treated with immunosuppressive agents are more susceptible to fungal and mycobacterial infections. The currently available evidence suggests an increased risk of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection with the use of TNFi’s.2,3 However, the occurrence of non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections with the use of biologics is not well established.

In a case-control study, of 30,772 patients receiving a TNFi, 158 (0.51%) developed targeted fungal and/or mycobacterial infections. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections were identified in 11% of these patients. The study also looked at the odds ratio for patients taking different TNFi’s compared with etanercept to evaluate how likely a patient would be treated for a fungal or mycobacterial infection. For adalimumab vs. etanercept, the odds ratio was 1.05 (0.69–1.62), infliximab vs. etanercept 1.08 (0.66–1.77), and for certolizumab vs. etanercept 0.78 (0.07–8.21). Thus, the study did not see a statistically significant difference between different TNFi’s when compared to etanercept.4

Figure 3. High-resolution computed tomography of the chest demonstrated sub-centimeter, scattered nodularity consistent with disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex.

A retrospective cohort study involving 42,180 rheumatoid arthritis patients suggested the occurrence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis varied with different biologic therapies. The hazard ratio for adalimumab was 1.52 (1.18–1.96), etanercept 1.16 (0.9–1.41) and rituximab 0.08 (0.02–0.31) using conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs-exposed patients as a reference group.5

Another retrospective cohort study involving 951 patients evaluated the occurrence of tuberculosis in RA patients on biologics. The findings suggested a higher Mycobacterium tuberculosis risk for patients receiving etanercept and adalimumab, but not for those receiving golimumab, abatacept, tocilizumab or tofacitinib.6

A retrospective study was conducted to identify the occurrence of non-tuberculous mycobacterial and tuberculosis cases among 8,418 patients with inflammatory diseases who received anti-TNF therapy. The occurrence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial disease was found to be fivefold higher in those receiving a TNFi than in those not receiving a TNFi and tenfold more elevated than in the general population. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial cases occurred more frequently among patients taking a TNFi, and interestingly, these patients were more likely to have chronic lung disease and gastroesophageal reflux disease.7

The currently available evidence suggests an increased risk of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection with the use of TNFi’s. However, the occurrence of non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections with the use of biologics is not well established.

The study of non-tuberculous mycobacterial diseases is a recent development. The diagnosis may be delayed given the atypical and subtle presentations of non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections.

In our patient, reactivation of MAC in the lung in the setting of TNFi therapy led to disseminated disease with the active involvement of a single joint. This is an undescribed and uncommon finding as far as we were able to identify in the literature.

Many existing guidelines and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate the importance of screening all patients for latent Mycobacterium tuberculous infections before initiating a TNFi.8,9 Doing so involves taking a close history of tuberculosis risk factors and the use of at least one diagnostic test for tuberculosis (i.e., interferon-γ release assay or tuberculin skin test). Despite the health risks associated with non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections and its unpredictable presentation, screening for these infectious processes before initiating TNFi has not been standardized in practice.

Identifying the risk of non-tuberculous mycobacterial disease is challenging. During screening, physicians should consider obtaining sputum for culture if patients have a chronic unexplained cough or chest radiograph/computerized tomography scan suggestive of infiltrate or bronchiectasis.

Finally, pulmonary or infectious disease referral for confirmation of diagnosis should be considered.

Bradley Bohman, MD, is a third-year post-graduate in the internal medicine residency program at the University of Arizona, Tucson.

Bradley Bohman, MD, is a third-year post-graduate in the internal medicine residency program at the University of Arizona, Tucson.

Jawad Bilal, MBBS, is an assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology at the University of Arizona, Tucson.

Jawad Bilal, MBBS, is an assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology at the University of Arizona, Tucson.

References

- Zella S, Keiphof J, Haghikia A, et al. Successful therapy with rituximab in three patients with probable neurosarcoidosis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2018 Oct 26;11:1756286418805732.

- Dobler CC. Biologic agents and tuberculosis. Microbiol Spectr. 2016 Dec; 4(6).

- Ai JW, Zhang S, Ruan QL, et al. The risk of tuberculosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tumor necrosis factor-α antagonist: A metaanalysis of both randomized controlled trials and registry/cohort studies. J Rheumatol. 2015 Dec;42(12):2229–2237.

- Salt E, Wiggins AT, Rayens MK, et al. Risk factors for targeted fungal and mycobacterial infections in patients taking tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016 Mar;68(3):597–603.

- Liao TL, Lin CH, Chen YM, et al. Different risk of tuberculosis and efficacy of isoniazid prophylaxis in rheumatoid arthritis patients with biologic therapy: A nationwide retrospective cohort study in Taiwan. PLoS One. 2016 Jun;11(4):e0153217.

- Lim CH, Chen HH, Chen YH, et al. The risk of tuberculosis disease in rheumatoid arthritis patients on biologics and targeted therapy: A 15-year real world experience in Taiwan. PLoS One. 2017 Jun 1;12(6):e0178035.

- Winthrop KL, Baxter R, Liu L, et al. Mycobacterial diseases and antitumour necrosis factor therapy in USA. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Jan;72(1):37–42.

- Diel R, Hauer B, Loddenkemper R, Manger B, Krüger K. [Recommendations for tuberculosis screening before initiation of TNF-α-inhibitor treatment in rheumatic diseases.] [article in German.] Z Rheumatol. 2009 Jul;68(5):411–416.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tuberculosis associated with blocking agents against tumor necrosis factor-α—California, 2002–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004 Aug 6;53(30):683–686.