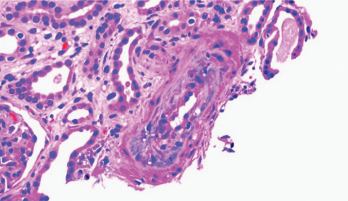

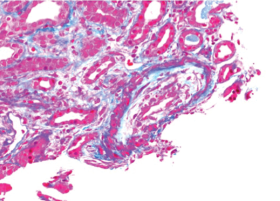

Figure 1. Thickening of the media layer of the vessel with narrowing of the arterial lumen is shown.

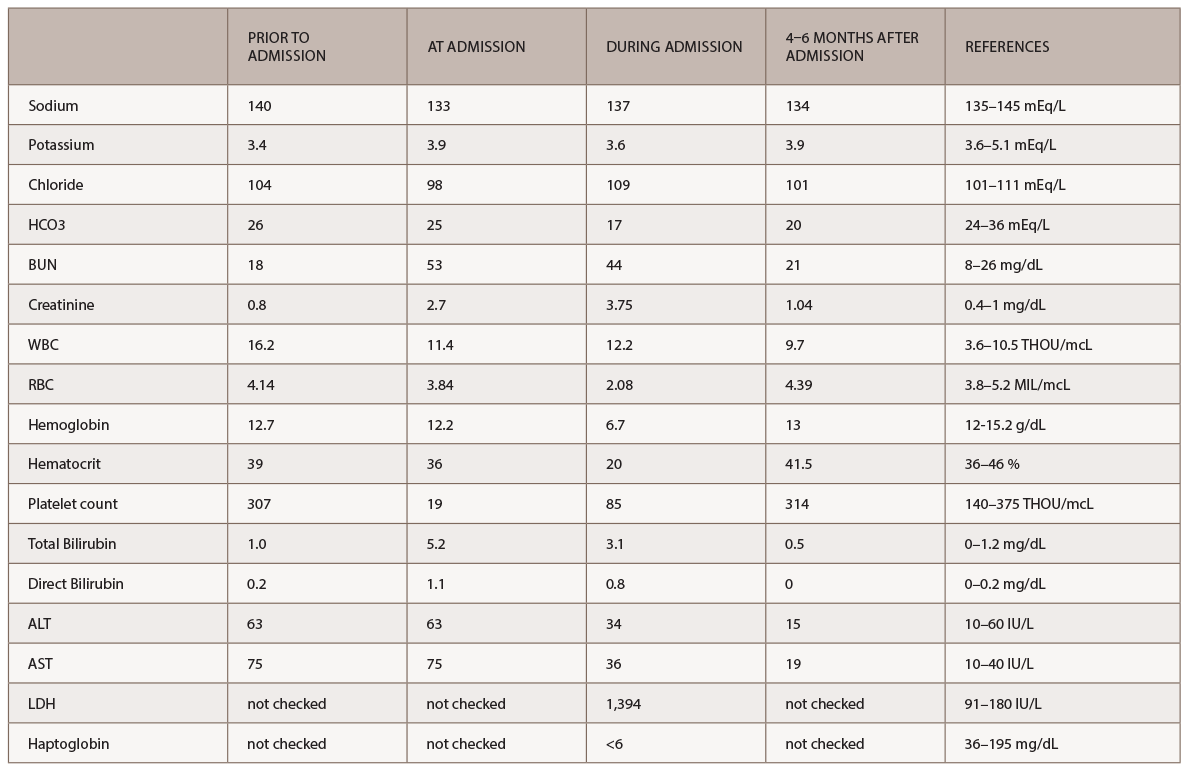

Scleroderma renal crisis (SRC) is a life-threatening complication of systemic sclerosis. SRC occurs in 2–15% of patients with diffuse sclerosis and usually within the first five years from the time of diagnosis.

Risk factors for SRC include, but are not limited to, early diagnosis, corticosteroid or cyclosporine use, and the presence of anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies. Usually, presenting symptoms include acute onset of hypertension and rapid deterioration of renal function.1 About 10% of patients present with normal blood pressure, making diagnosis more challenging and often delaying treatment. The prognosis is poor, with a five-year survival rate of less than 60%.1

Case Presentation

Three months before hospital admission

A 63-year-old woman with a past medical history of gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) presented to her primary care physician with new onset pain and swelling of her hands, a faint rash on her bilateral inner thighs and forearms, and Raynaud’s phenomenon. The patient was referred to a rheumatologist and a dermatologist.

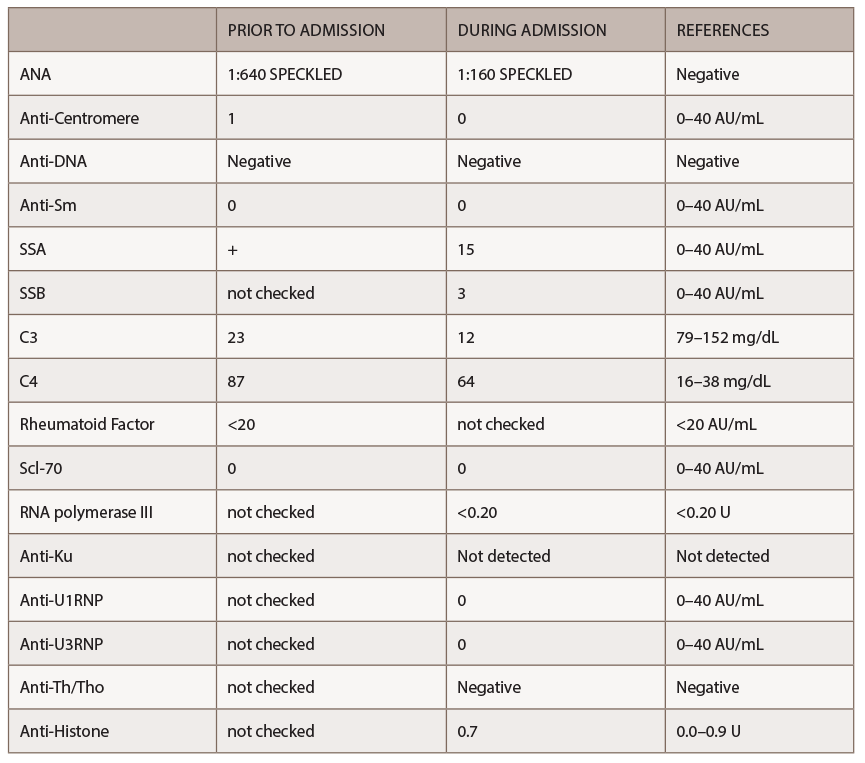

The initial rheumatologic evaluation, which was completed at another facility, was consistent with an inflammatory arthritis. Her autoimmune workup was remarkable for a positive anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) at a titer of 1:640 in a speckled pattern and positive SSA, but was negative for anti-scleroderma 70 (anti-Scl70), anti-centromere, anti-double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA), anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP), rheumatoid factor (RF), anti-Jo1 and anti-Smith (anti-Sm) antibodies.

The patient was also evaluated by a dermatologist. Two skin biopsies were obtained. The biopsy of the inner thigh was consistent with neutrophilic urticaria, and the biopsy from the forearm was consistent with morphea profunda. The patient was started on 20 mg of methotrexate weekly by the dermatologist, but developed nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain, so methotrexate was discontinued and high-dose prednisone (60 mg/day) was initiated.

At the time of admission

One month after starting the prednisone, the patient presented to the emergency department with complaints of severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, jaundice, decreased appetite, unintentional 20 lb. weight loss, chills and fevers. On physical exam, the patient was tachycardic with a heart rate of 115. She was lethargic and pale, with scleral icterus. She also had weakness of her bilateral upper and lower extremities, and diffuse abdominal tenderness.

Figure 2. There is necrosis within the media layer of the vessel which is highly indicative of scleroderma renal crisis.

Laboratory tests revealed severe anemia, leukocytosis, severe thrombocytopenia, transaminitis and acute kidney injury with both hematuria and proteinuria (see Table 1). In addition, the LDH was elevated (1,394 IU/L, see Table 1), and the peripheral smear demonstrated multiple schistocytes. Nephrology and hematology specialists were consulted. Due to the patient’s acute presentation, there was a great concern for thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP).

One day after admission, plasmapheresis was initiated. Despite this treatment, the patient’s renal function continued to deteriorate, and her creatinine increased from 2.5 to 3.7 mg/dL. When her ADAMTS13 level was noted to be elevated (77%), our suspicion for atypical TTP was raised.

The patient continued to be confused, weak and icteric. She also complained of pain in multiple joints, especially her hands. At this time, the rheumatology service at our hospital was consulted.

On the rheumatology clinical examination, this patient had sclerodactyly, extensive thickening of the skin on her face, the skin from her hands to above her elbows and the skin from her feet to her thighs. She had contractures of the hands, and she couldn’t make a full fist. Telangiectasia were noted over her face. There was no periungual erythema, capillary dilatations or calcinosis.

A new battery of autoimmune tests (see Table 2) was obtained and showed only positive ANA (1:160 speckled). Anti-Scl70, anticentromere, anti-RNA polymerase III, anti-Th/To and anti-U1RNP were all negative. This time, SSA, SSB, anti-Sm and anti-dsDNA antibodies were negative. Complement levels were within normal limits. A CT of the chest demonstrated nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) and small bilateral pleural effusions.

Based on the clinical exam findings—specifically, the extensive skin thickening of the face, chest, and upper and lower extremities—the rheumatology team noted this patient satisfied the 2012 ACR classification criteria for definite diagnosis of diffuse systemic sclerosis. Because of the patient’s recent exposure to high-dose steroids and rapid deterioration of renal function, despite a normal blood pressure, the rheumatology consult service suspected SRC.

Per the consulting nephrologist’s request, a kidney biopsy was performed. Renal pathology demonstrated onion skin proliferation within the walls of the intrarenal arteries and arterioles, fibrinoid necrosis and glomerular shrinkage.

Based on these findings, a diagnosis of SRC was made. Plasma exchange was stopped, and captopril was initiated. After captopril was started, the patient’s serum creatinine started to stabilize at a value of 3.3 mg/dL.

Twelve months after initiation of treatment, the patient’s kidney function recovered completely, allowing the patient to avoid hemodialysis. She was placed on mycophenolic acid for her skin involvement and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). The patient’s skin thickening has regressed, and now involves only the wrists and calves, with improvement in her respiratory symptoms.

Discussion

Scleroderma renal crisis is a dreaded complication of systemic sclerosis. Usually, SRC is characterized by new-onset hypertension, acute severe renal failure and, in some cases, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia in combination with thrombocytopenia.

The three main risk factors recognized for SRC are skin involvement with a score of more than 10 based on ACR criteria, prednisone exposure at doses higher than 20 mg/day or prolonged use of lower doses, and the presence of anti RNA polymerase III antibodies.3,4

In most cases, hypertension in SRC is defined as a blood pressure above 150/90 mmHg or an increase in blood pressure of 10–20 mmHg above baseline. Cases described in a 2012 study from Guillevin et al. indicated 14% of patients with SRC presented without hypertension.5

Renal failure in SRC is defined as a drop in eGFR of at least 30% or elevation of creatinine 50% above baseline. A renal biopsy can be helpful, but is not required for the diagnosis of SRC, especially if there is a high suspicion and a response to therapy. Renal biopsy may be beneficial, however, in cases in which the diagnosis is inconclusive or evidence of multiple processes exists. In such cases, therapy should be initiated empirically, because a delay in treatment is associated with a poor prognosis.

Hematologic manifestations of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia can occur, but the pathogenesis of these findings remains unclear.

The mainstay of treatment of SRC is angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I). ACE-I should be started and continued even if creatinine levels continue to rise or the patient’s blood pressure has normalized. There is no role of prophylactic ACE-I therapy for prevention of SRC because it paradoxically seems to increase the patient’s risk for developing SRC. Unfortunately, 40–66% of patients never recover renal function, and some will require chronic dialysis. Median recovery time is one year; it is, therefore, prudent to delay evaluation for renal transplantation. Van den Born et al. reported that a modified Rodnan skin score >20, cardiac involvement and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia are all associated with a poor prognosis in these patients.1

Our patient was treated with as much as 60 mg of prednisone daily for approximately two months prior to presentation due to a misdiagnosis of seronegative inflammatory arthritis. The patient had no underlying history of hypertension or systemic sclerosis. Three months before admission to our hospital, the patient had a baseline creatinine of 0.8 mg/dL and a normal glomerular filtration rate. The acute onset of renal failure at the time of her admission led the primary team to consider atypical TTP and ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis in their initial differential diagnosis. ANCA antibodies were negative, which argued against an ANCA-associated vasculitis.

The rheumatology team, based on the patient’s recent history, clinical exam and autoantibody profile, diagnosed this patient with diffuse systemic sclerosis and suspected SRC immediately. The diagnosis was unusual given the patient’s prior good health and her age at the time of diagnosis. Further, anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies were absent.

Although initially, the patient was treated empirically for TTP with daily plasma exchanges, the patient’s serum creatinine level continued to rise. After the suspicion of SRC was raised, therapy with captopril was initiated, and fortunately for our patient, her renal function recovered within 12 months.

Conclusion

This is a remarkable case of a relatively healthy 63-year-old woman who was initially diagnosed as having an inflammatory arthritis, but was later found to have systemic sclerosis. Rapid intervention by the rheumatology team and initiation of proper treatment led to an excellent outcome. Fortunately, the patient’s renal function recovered completely and gave this patient a chance to live a normal life.

Adria Madera-Acosta, MD, is a second year resident in internal medicine at Trihealth Physician Partners, Cincinnati.

Adria Madera-Acosta, MD, is a second year resident in internal medicine at Trihealth Physician Partners, Cincinnati.

Teresa Sosenko, MD, is a first-year rheumatology fellow at the University of Illinois College of Medicine.

Teresa Sosenko, MD, is a first-year rheumatology fellow at the University of Illinois College of Medicine.

Diana Girnita, MD, PhD, is a rheumatologist at Trihealth Physician Partners, Cincinnati, and a faculty attending for the internal medicine residency program at Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati.

Diana Girnita, MD, PhD, is a rheumatologist at Trihealth Physician Partners, Cincinnati, and a faculty attending for the internal medicine residency program at Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati.

References

- Denton CP, Lapadula G, Mouthon L, Müller-Ladner U. Renal complications and scleroderma renal crisis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009 Jun;48 Suppl 3:iii32–35.

- Abudiab M, Krause ML, Fidler ME, et al. Differentiating scleroderma renal crisis from other causes of thrombotic microangiopathy in a postpartum patient. Clin Nephrol. 2013 Oct;80(4):293–297.

- Bhavsar SV, Carmona R. Anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies in the diagnosis of scleroderma renal crisis in the absence of skin disease. J Clin Rheumatol. 2014;20(7):379–382.

- Maruyama A, Nagashima T, Ikenoya K, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced normotensive scleroderma renal crisis: A report on two cases and a review of the literature in Japan. Intern Med. 2013;52(16):1833–1837.

- Guillevin L, Bérezné A, Seror R, et al. Scleroderma renal crisis: A retrospective multicentre study on 91 patients and 427 controls. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51(3):460-467.