Figure 1. Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp. Note the areas of alopecia where subcutaneous abscesses are located.

Synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis and osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome is a heterogeneous, inflammatory, musculoskeletal disease. The disease is an insidious, sterile osteitis with associated skin and synovial inflammation.1 Diagnosis can prove challenging, but a thorough clinical history, high clinical suspicion and imaging techniques can help clinch it.

The below case reveals a rare, fulminant presentation of SAPHO syndrome in which signature imaging findings helped us achieve diagnosis. It highlights an unusual combination of multilevel spinal involvement, scalp and extremity dissecting cellulitis, and osteitis with the signature bull’s head sign on scintigraphy. This unique presentation required excluding mimics, such as spondyloarthropathy, infection, malignancy and other immunodeficiencies.

The Case

A 28-year-old black man arrived at our rheumatology clinic in a wheelchair pushed by his mother. He appeared very stiff and uncomfortable and had been confined to the wheelchair for about eight weeks prior to his arrival.

He was in marked distress as he and his mother described his history. He developed acute onset of back and neck pain about 10 weeks prior to his visit. About six weeks prior to his presentation, he developed arthritis of the knees and left shoulder, as well as a scaly rash on his left lower leg and scalp. The rash on his scalp progressed to itching and oozing lesions. He completely lost his appetite, which was associated with a 30 lb. weight loss since the onset of symptoms. He denied any fever, but did describe subjective chills and constant fatigue. After the onset of arthritis, he became almost entirely confined to the wheelchair because the pain and stiffness became so severe that weight bearing was difficult. In fact, it was painful to sit upright in the wheelchair while his mother navigated him from place to place for his daily activities.

He had no significant past medical or surgical history and took no medications. He reported consuming large amounts of acetaminophen and ibuprofen daily to alleviate his severe pain and discomfort. He denied a family history of inflammatory joint disease, psoriasis or malignancy. He denied ever using illicit substances, drinking alcohol, using tobacco products or recent travel.

He was afebrile, but on examination appeared ill and in obvious discomfort. He was so stiff he resembled a statue sitting in the wheelchair. His scalp featured multiple, purulent, draining areas of fluctuance erythema and edema (see Figure 1). Palpation of his neck revealed bilateral, small, tender lymph nodes. The rash on his left lower leg was less purulent and more eczematous and scaly on an erythematous base.

Tenderness to palpation of his cervical and thoracic spine was noted, and his range of motion in his neck and mid back was severely limited. His right knee was swollen and warm, and his range of motion was decreased due to pain. His left shoulder revealed warmth and swelling, and he had decreased range of motion on adduction and internal and external rotation. A full assessment of his strength was not possible, because pain prevented him from standing up.

Due to the severity and marked constitutional symptoms, he was admitted to the hospital for urgent evaluation. Laboratory analysis revealed elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) of 152.4 mg/L and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 98 mm/hr. Screening for anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA), rheumatoid factor (RF), human leukocyte antigen B27 (HLA-B27), tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus antibodies, viral hepatitis, parvovirus serologies and chlamydial infection was all negative. His cerebrospinal fluid was evaluated for infection, and no evidence of bacterial, fungal or tuberculous meningitis was found.

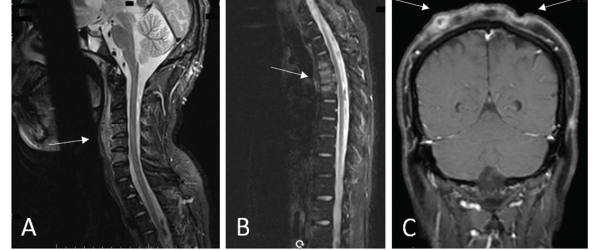

X-rays of his left shoulder revealed mild periosteal elevation and hyperostosis of the proximal humerus and distal acromion, and the radiograph of his right knee revealed a subtle osteolytic, erosive lesion on the lateral side of the femur near the joint margin. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine revealed multifocal, enhancing lesions consistent with marrow edema (see Figures 2A and 2B, below). The brain MRI did not reveal any intracranial lesions, but clearly revealed the cutaneous abscesses on his scalp (see Figure 2C).

Figures 2a, b, c

(A) An MRI of the cervical spine revealed multilevel, anterior-predominant, marrow edema extending from C3–C7 with paravertebral edema anteriorly (see white arrow). (B) An MRI of the thoracic spine revealed marrow edema of T3–T5 with mild anterior, superior corner erosion of T5 (see white arrow). (C) An MRI of the brain revealed no intracranial lesions, but note the obvious cellulitis and abscess formation on the scalp (see white arrows).

A biopsy of the T4 vertebral body revealed no evidence of bacterial, acid-fast bacilli, fungal or mycobacterial infection. Surgical pathology of the T4 vertebra revealed only hypercellular marrow tissue without evidence of malignancy.

Presumptive diagnosis: undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy, given his axial and peripheral inflammatory disease. Initial therapy included prednisone and methotrexate.

Clinically, he showed some improvement and was discharged to follow-up care with dermatology and rheumatology clinics. Dermatology performed a biopsy of the scalp lesions that revealed histologic findings consistent with dissecting cellulitis of the scalp. He was also diagnosed with acne keloidalis nuchae.

Upon follow-up in the rheumatology clinic, he showed only modest improvement on methotrexate and prednisone. A nuclear bone scan was performed, revealing hypermetabolic lesions of his cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine, his sterno-manubrio-clavicular joints, his left shoulder and his right knee. The lesion of the sternoclavicular site provided the bull’s head sign (see Figure 3), and the diagnosis of SAPHO syndrome was confirmed given the constellation of findings.

Figure 3. A whole-body bone scintigraphy revealed the pathognomonic finding of the bull’s head enhancement correlating with osteitis of the sterno-manubrio-clavicular articulations bilaterally (see red arrow). You can also see the enhancement in the spine, both knees, left shoulder and right maxillary/mandibular regions.

Infliximab therapy was initiated, which led to significant improvements in synovitis, stiffness and dermatitis. Both prednisone and methotrexate therapy were later tapered off, and he continues to do well on anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy.

He was referred to physical therapy and now ambulates independently. He has regained his appetite, and his weight has returned to normal.

Discussion

SAPHO syndrome is a rare, heterogeneous, inflammatory disease affecting osteoarticular and cutaneous tissues.1 It has many previous names, a few of which include bilateral clavicular osteomyelitis with palmoplantar pustulosis, subacute and chronic clavicular osteomyelitis, sternoclavicular hyperostosis and chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO).2

The classification of SAPHO syndrome is debated because it shares characteristics with spondyloarthritides, sterile dermatoses and osteitis, and auto-inflammatory diseases. The scarce epidemiologic data available seems to link SAPHO to alterations in genes PSTPIP2, PSTPIP1, LPIN2 and NOD2, which are found in several other auto-inflammatory diseases, but no clear causal relationship has been established. A relationship with HLA-B27 positivity also remains controversial because literature both supports and negates an HLA-B27 association with SAPHO.1,2

Clinical findings include enthesitis, sacroiliitis, peripheral arthritis and axial hyperostosis, mimicking spondyloarthropathies. But several features of SAPHO relate to auto-inflammatory diseases, such as histological infiltrates dominated by neutrophils resembling sterile, neutrophilic dermatoses.1,2 Overall, SAPHO’s poor association with HLA-B27 seems to argue against SAPHO being a member of the spondyloarthropathies.3,4

Women are more commonly affected by SAPHO than men in the small cohorts providing epidemiologic data, and the disease seems to manifest in the fourth to fifth decade of life, although it can present at any age.3-5 Our patient highlights a rare presentation because the individual was a man in his 20s.

Consistent clinical findings of SAPHO include the insidious onset of inflammatory polyarthritis, sterno-manubrio-clavicular joint arthritis and the presentation of cutaneous disease antedating skeletal disease. Up to 55% of sufferers will experience skin symptoms prior to rheumatic symptoms, and peripheral arthritis is more commonly reported than axial disease at any spinal level. The most common dermatoses described are palmar-plantar pustulosis, severe and pustular acne, and hidradenitis suppurativa.

African-American individuals with SAPHO seem to suffer higher incidences of hidradenitis suppurativa than other dermatoses.6 Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp is a rare, but reported, finding in SAPHO.4 Most commonly, SAPHO follows a self-limiting course that usually resolves within 3–12 months or, unusually, a persistent and relapsing course that frequently requires indefinite therapy.5 Rarely, it may present in a fulminant manner with simultaneous skin, joint and skeletal disease, as our patient demonstrated.

He was so stiff he resembled a statue sitting in the wheelchair.

Diagnosis is challenging because validated classification criteria and laboratory biomarkers do not exist. Two sets of classification criteria are commonly used, one proposed by Benhamou et al. in 1988, and the other proposed by Kahn and Kahn in 1994, which was then modified for presentation at the ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting in 2003.7,8

Our case fulfilled one of Benhamou’s criteria: hyperostosis of the anterior chest wall with dermatosis. It also satisfied two of Kahn’s criteria: bone joint disease associated with severe acne and sterile osteitis (Note: only one criterion is required for both proposed criteria).7,8

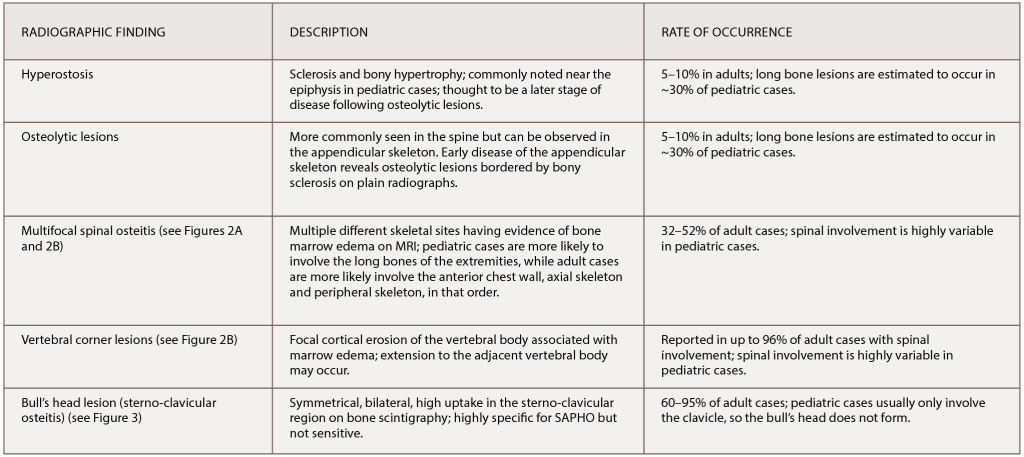

(click for larger image) Table 1: The Most Common Radiographic Observations of SAPHO Syndrome

References: Nguyen et al. (2012); Depasquale et al. (2012).

As discussed, HLA-B27 positivity did not correlate well with the diagnosis, and neither did elevations in the ESR nor CRP.3-5 Diagnosis is entirely clinical, requiring a high degree of suspicion and pattern recognition of the classic symptoms, clinical signs and imaging findings.

There is balance in the literature regarding therapeutic agents. Physicians should choose therapy on an individual basis. Several different agents have been used and suggested as efficacious by small cohorts and case reports.9 Tailoring the treatment approach to disease phenotype severity can help.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, oral bisphosphonates, systemic corticosteroids and conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs all exhibit the potential to reduce symptoms and manage mild arthritis.4,9 These therapies may be used in mild cases that may spontaneously remit in the future. TNF inhibitors show especially strong potential (albeit in small trials) as remission-inducing agents, and our case highlights another successful outcome with TNF therapy for severe disease.9

Radiographic Findings in SAPHO

Classic findings on radiologic examination may be the key to early diagnosis of SAPHO syndrome due to its variability in clinical presentation. SAPHO syndrome can cause multiple different bony lesions on imaging (see Table 1), but the signature lesion is osteitis of the sterno-manubrio-clavicular articulation (i.e., the anterior chest wall syndrome). Osteitis of these four bones creates a bull’s head sign produced by the shape of hyperintensity signaling seen on bone scintigraphy (see Figure 3).

Next, multifocal areas of vertebral bone marrow edema consistent with osteitis appear on MRI (see Figures 2A and 2B). Vertebral lesions are classically described as corner lesions owing to the bone edema usually associated with erosion found at the anterior corners of the vertebral bodies (see Figure 2B). These lesions are difficult to differentiate from infectious and malignant bone lesions, so biopsy is usually required to evaluate the differential diagnoses.

Hyperostosis noted on plain X-ray can appear and is most commonly noted in the clavicle (although the radiographs of our patient revealed hyperostosis of the proximal humerus and distal acromion). Finally, in contrast to hyperostosis lesions, osteolytic lesions may be discovered as well.6,10

Our patient’s presentation was unique because it included all the typical imaging findings of SAPHO, and this constellation of radiographic findings was key in clinching the diagnosis.

Conclusion

SAPHO syndrome remains a poorly understood disease and is thought, at this time, to be rare. The literature describing SAPHO suggests it can present in a myriad of ways. Our case was unique because it occurred in a black man and featured fulminant onset, all the classic radiographic findings and a rarely associated dissecting cellulitis dermatosis.

Several treatment options are available for SAPHO. Our patient’s fulminant course was successfully treated with anti-TNF therapy. Physical therapy, topical steroids and antibiotics for skin lesions add to the therapeutic armamentarium.

Still, we need larger cohorts and collaborative studies to better define efficacy and outcomes in the management of SAPHO syndrome.

Ross J. Thibodaux, MD, is a rheumatology fellow in the Division of Rheumatology at the Louisiana State University Health Science Center in New Orleans.

Ross J. Thibodaux, MD, is a rheumatology fellow in the Division of Rheumatology at the Louisiana State University Health Science Center in New Orleans.

Nirupa J. Patel, MD, is an associate professor in the Division of Rheumatology at the Louisiana State University Health Science Center in New Orleans.

Nirupa J. Patel, MD, is an associate professor in the Division of Rheumatology at the Louisiana State University Health Science Center in New Orleans.

References

- Firinu D, Garcia-Larsen V, Manconi PE, et al. SAPHO syndrome: Current developments and approaches to clinical treatment. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2016 Jun;18(6):35.

- Rukavina I. SAPHO syndrome: A review. J Child Orthop 2015 Feb;9(1):19–27.

- Aljuhani F, Tournadre A, Tatar Z, et al. The SAPHO syndrome: A single-center study of 41 adult patients. J Rheumatol. 2015 Feb;42(2):329–334.

- Li C, Zuo Y, Wu N, et al. Synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis and osteitis syndrome: A single centre study of a cohort of 164 patients. Rheumatol (Oxford) 2016 Jun;55(6):1023–1030.

- Colina M, Govoni M, Orzincolo C, et al. Clinical and radiologic evolution of synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis syndrome: A single center study of a cohort of 71 subjects. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Jun 15;61(6):813–821.

- Nguyen MT, Borchers A, Selmi C, et al. The SAPHO syndrome. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012 Dec;42(3):254–265.

- Benhamou CL, Chamot AM, Kahn MF. Synovitis-acne-pustulosis-hyperostosis-osteomyelitis syndrome (SAPHO). A new syndrome among the spondyloarthropathies? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1988 Apr–Jun;6(2):109–112.

- Kahn MF, Khan MA. The SAPHO syndrome. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1994 May;8(2):333–362.

- Zwaenepoel T, Vlam KD. SAPHO: Treatment options including bisphosphonates. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016 Oct;46(2):68–173.

- Depasquale R, Kumar N, Lalam RK, et al. SAPHO: What radiologists should know. Clin Radiol. 2012 Mar;67(3):195–206.