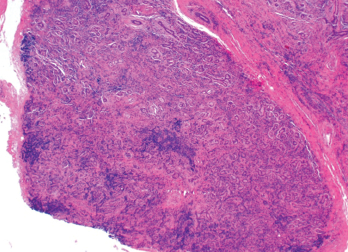

Figure 2. An ultrasound-guided biopsy revealed necrotizing granulomatous inflammation in the liver.

Given his prior latent TB infection and positive QuantiFERON-TB Gold, he was evaluated by the public health department and started on TB therapy (rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol [RIPE]). Very soon after this, further research raised concern for chronic allopurinol-induced granulomatous hepatitis. His alkaline phosphatase prior to dose escalation of the allopurinol was 153 U/L, peaking months later at 308 U/L. Allopurinol-induced granulomatous hepatitis was felt to be the primary etiology, and RIPE therapy was discontinued. Allopurinol was discontinued, and he was started on 80 mg of febuxostat daily. His alkaline phosphatase had peaked at 308 U/L and slowly trended back down to 150–160 U/L.

Three years later, a noncontrast MRI of his liver demonstrated two stable liver lesions with no further lesions recognized on this study. Repeat labs obtained this year showed overall stable liver function tests, with an alkaline phosphatase of 157 U/L. He is followed by a hepatologist for his cirrhosis secondary to both his nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and his granulomatous liver disease.

His rectal mass was also further investigated. A colonoscopy did not reveal an intraluminal mass, and given the stability of this lesion on imaging, it was believed to be a benign finding.

His gout remains well controlled on 80 mg of febuxostat daily. He has a serum urate of 5.2 mg/dL and has had no recurrence of gout flares.

Discussion

Figure 3. An X-ray of the patient’s left hand showed numerous erosions with overhanging edges due to gout.

Hepatic granulomas are found in 2–10% of all patients undergoing liver biopsy.1 The most common etiologies include sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, neoplasms and primary biliary cholangitis. They can also be drug induced. Even with extensive investigation, 10–36% of patients with hepatic granulomas will have no identifiable cause.2

A diagnosis of drug-induced granulomatous hepatitis is a diagnosis of exclusion, necessitating evaluation for other common etiologies and evaluating the temporal relationship with the offending drug. Commonly used medications implicated in granulomatous hepatitis include allopurinol, nitrofurantoin, phenytoin, carbamazepine, diltiazem, hydralazine, methyldopa, procainamide, quinidine, azathioprine and sulfa-

containing drugs.3

Allopurinol-induced granulomatous hepatitis has been noted in numerous case reports dating back to the 1970s.4,5 Given our patient’s presentation and clinical course, we feel he had convincing evidence of this condition. Our extensive workup for other etiologies of granulomatous hepatitis was unrevealing. The elevation in alkaline phosphatase temporally correlating with the rapid up-titration of allopurinol and its subsequent decline, with resolution of most liver lesions after discontinuation, added confidence to this diagnosis. His alkaline phosphatase remaining mildly elevated after removal of allopurinol is most likely due to his NASH cirrhosis, because it was previously mildly elevated as well.

Prior case reports on this condition have shown improvement in hepatic lesions after discontinuation of allopurinol. However, some of our patient’s hepatic lesions persisted, and it is possible his fibrotic liver may be a contributor to the lack of resolution on follow-up imaging.

Allopurinol-induced granulomatous hepatitis is a rare adverse reaction to allopurinol use. More commonly, allopurinol causes reversible hepatotoxicity with asymptomatic elevations of serum alkaline phosphatase in 3–5% of patients.6 In most cases of reported allopurinol-induced granulomatous hepatitis, the elevation in alkaline phosphatase is noted in the weeks or months following the initiation of therapy, although the reaction has been reported to occur as late as five years after allopurinol initiation.5

Other cases have demonstrated a collection of other systemic symptoms. A case of allopurinol-induced granulomatous hepatitis described in 1972 was accompanied by fever, weight loss and eosinophilia, which all resolved upon discontinuation of allopurinol.4

Other well-described and more prevalent adverse effects of allopurinol exist. A common reaction is an increased incidence of gout flares during initiation of therapy, as possible in any urate-lowering therapy. The frequency of flares decreases with time, and the standard of care is to administer daily colchicine or another non-steroidal anti-