Case Presentation

A 45-year-old man with crystal-proven gout, poorly controlled diabetes and chronic kidney disease was lost to follow-up for six years and presented back to the VA clinic in the midst of a gout flare. He stated he had continued taking 100 mg of allopurinol daily, but his serum urate level was 13.8 mg/dL. He described numerous gout flares over the past few months.

He denied fevers, chills, abdominal pain or a change in bowel habits. He reported chronic fatigue and recent weight gain. His vital signs were all within normal limits.

The physical exam showed the patient was obese (BMI 40) and had mild swelling and warmth in all proximal interphalangeal joints, metacarpophalangeal joints and both wrists. His knees and elbows had noticeable warmth, but were without swelling. Chronic tophaceous buildup was easily palpable at numerous joints, and his range of motion was grossly maintained throughout. He was otherwise without abdominal pain, hepatomegaly, lymphadenopathy or rashes.

After management of the acute gout flare, his allopurinol dose was increased, and he was started on daily colchicine for gout flare prophylaxis. He complied with his medication regimen and showed significant symptomatic improvement. Over the next four months, his allopurinol dose was rapidly escalated to 600 mg daily, reducing his serum urate level to 4.8 mg/dL.

Shortly afterward, he was found to have moderately elevated transaminases and a greatly elevated alkaline phosphatase at 308 U/L (upper limit of normal 126 U/L). An abdominal ultrasound showed cirrhosis and interval development of multiple hypoechoic lesions throughout the liver, concerning for metastatic disease or hepatocellular carcinoma. Computerized tomography (CT) of the abdomen also demonstrated numerous ill-defined hypodense lesions all throughout the liver (see Figure 1), suspicious for metastatic disease, along with a 1.9×2.9 cm mesorectal mass concerning for colorectal cancer.

Figure 1. A CT of the abdomen demonstrated numerous hypodense lesions present in both lobes of the liver, with the largest lesion measuring 2.0 x 3.1 cm.

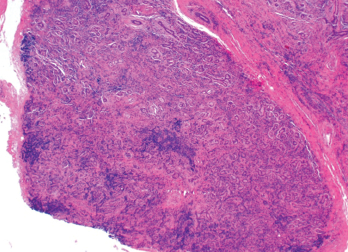

This was followed up by a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of his abdomen, which corroborated the previous hepatic findings. All lesions on the MRI were deemed stable since the earlier CT, and no new lesions were noted. We felt it would be unlikely for the hepatic lesions to be metastatic disease due to stable preexisting lesions and the lack of new lesions in this time frame. An ultrasound-guided biopsy was performed, which revealed necrotizing granulomatous disease (see Figure 2).

Given this granulomatous disease and history of polyarthralgia, sarcoidosis was considered. Plain films were updated, and an MRI of his hands was obtained to determine if his arthropathy and liver disease could be due to sarcoidosis; however, the MRI was remarkable only for lesions consistent with a crystalline arthropathy (see Figure 3). Serum angiotensin I-converting enzyme and vitamin D levels were also not supportive of sarcoidosis.

Infectious etiologies were high on the differential for his granulomatous disease, especially after it was noted our patient had a latent tuberculosis (TB) infection when he was a child in the 1980s. He had received at least one month of treatment for latent TB, but was unsure of any further details of his treatment. Acid-fast bacilli and Gomori methenamine silver stains of the biopsy specimen were negative.

An infectious disease specialist was subsequently consulted. The patient denied fevers or chills, but he reported fatigue and recent weight gain.

He had worked as a long-haul truck driver and had a military history with deployment to the Persian Gulf. Serologies obtained for cryptococcus, histoplasma and coccidioides were unremarkable. QuantiFERON-TB Gold was positive, not unexpected given his latent TB infection as a child. A repeat liver biopsy found granulomatous inflammation with focal necrosis in a background of features compatible with cirrhosis, consistent with previous biopsy. The acid-fast bacilli smear was again negative.

Figure 2. An ultrasound-guided biopsy revealed necrotizing granulomatous inflammation in the liver.

Given his prior latent TB infection and positive QuantiFERON-TB Gold, he was evaluated by the public health department and started on TB therapy (rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol [RIPE]). Very soon after this, further research raised concern for chronic allopurinol-induced granulomatous hepatitis. His alkaline phosphatase prior to dose escalation of the allopurinol was 153 U/L, peaking months later at 308 U/L. Allopurinol-induced granulomatous hepatitis was felt to be the primary etiology, and RIPE therapy was discontinued. Allopurinol was discontinued, and he was started on 80 mg of febuxostat daily. His alkaline phosphatase had peaked at 308 U/L and slowly trended back down to 150–160 U/L.

Three years later, a noncontrast MRI of his liver demonstrated two stable liver lesions with no further lesions recognized on this study. Repeat labs obtained this year showed overall stable liver function tests, with an alkaline phosphatase of 157 U/L. He is followed by a hepatologist for his cirrhosis secondary to both his nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and his granulomatous liver disease.

His rectal mass was also further investigated. A colonoscopy did not reveal an intraluminal mass, and given the stability of this lesion on imaging, it was believed to be a benign finding.

His gout remains well controlled on 80 mg of febuxostat daily. He has a serum urate of 5.2 mg/dL and has had no recurrence of gout flares.

Discussion

Figure 3. An X-ray of the patient’s left hand showed numerous erosions with overhanging edges due to gout.

Hepatic granulomas are found in 2–10% of all patients undergoing liver biopsy.1 The most common etiologies include sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, neoplasms and primary biliary cholangitis. They can also be drug induced. Even with extensive investigation, 10–36% of patients with hepatic granulomas will have no identifiable cause.2

A diagnosis of drug-induced granulomatous hepatitis is a diagnosis of exclusion, necessitating evaluation for other common etiologies and evaluating the temporal relationship with the offending drug. Commonly used medications implicated in granulomatous hepatitis include allopurinol, nitrofurantoin, phenytoin, carbamazepine, diltiazem, hydralazine, methyldopa, procainamide, quinidine, azathioprine and sulfa-

containing drugs.3

Allopurinol-induced granulomatous hepatitis has been noted in numerous case reports dating back to the 1970s.4,5 Given our patient’s presentation and clinical course, we feel he had convincing evidence of this condition. Our extensive workup for other etiologies of granulomatous hepatitis was unrevealing. The elevation in alkaline phosphatase temporally correlating with the rapid up-titration of allopurinol and its subsequent decline, with resolution of most liver lesions after discontinuation, added confidence to this diagnosis. His alkaline phosphatase remaining mildly elevated after removal of allopurinol is most likely due to his NASH cirrhosis, because it was previously mildly elevated as well.

Prior case reports on this condition have shown improvement in hepatic lesions after discontinuation of allopurinol. However, some of our patient’s hepatic lesions persisted, and it is possible his fibrotic liver may be a contributor to the lack of resolution on follow-up imaging.

Allopurinol-induced granulomatous hepatitis is a rare adverse reaction to allopurinol use. More commonly, allopurinol causes reversible hepatotoxicity with asymptomatic elevations of serum alkaline phosphatase in 3–5% of patients.6 In most cases of reported allopurinol-induced granulomatous hepatitis, the elevation in alkaline phosphatase is noted in the weeks or months following the initiation of therapy, although the reaction has been reported to occur as late as five years after allopurinol initiation.5

Other cases have demonstrated a collection of other systemic symptoms. A case of allopurinol-induced granulomatous hepatitis described in 1972 was accompanied by fever, weight loss and eosinophilia, which all resolved upon discontinuation of allopurinol.4

Other well-described and more prevalent adverse effects of allopurinol exist. A common reaction is an increased incidence of gout flares during initiation of therapy, as possible in any urate-lowering therapy. The frequency of flares decreases with time, and the standard of care is to administer daily colchicine or another non-steroidal anti-

inflammatory agent during initiation to prevent these flares.

Also possible are numerous delayed hypersensitivity reactions, such as maculopapular exanthema, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Patients who are HLA-B*5801-genotype positive are at higher risk of developing these cutaneous reactions and should avoid allopurinol. This genotype is most often seen in patients of Korean, Han Chinese or Thai heritage.6

Other adverse effects seen with allopurinol use include gastrointestinal upset (e.g., nausea, diarrhea), drowsiness, leukopenia and thrombocytopenia.6

Conclusion

Allopurinol-induced granulomatous hepatitis is a rare phenomenon that rheumatologists should be aware of given the frequency with which this drug is used. A discovery of this condition should prompt a change in therapy to another urate-lowering agent, such as febuxostat, which has not had any reported cases of granulomatous hepatitis.

This case serves as a reminder that any clinical presentation without a clear etiology warrants a review of the patient’s medication list. It is not possible to know every rare, adverse reaction to medications, but identifying a temporal relationship between a drug and a clinical presentation can help guide our clinical suspicions.

Raj Vachhani, MD, is a third-year postgraduate, studying internal medicine at the University of Alabama, Birmingham.

Raj Vachhani, MD, is a third-year postgraduate, studying internal medicine at the University of Alabama, Birmingham.

Angelo L. Gaffo, MD, MSPH, is the rheumatology section chief at the Birmingham VA Medical Center and associate professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology at the University of Alabama, Birmingham.

Angelo L. Gaffo, MD, MSPH, is the rheumatology section chief at the Birmingham VA Medical Center and associate professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology at the University of Alabama, Birmingham.

References

- Lamps LW. Hepatic granulomas: A review with emphasis on infectious causes. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015 July;139(7):867–875.

- Zakim D, Boyer TD (Eds). Hepatology: A textbook of liver disease. Vol. 3. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1996:1472.

- Culver EL, Watkins J, Westbrook RH. Granulomas of the liver. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2016 Apr 27;7(4):92–96.

- Simmons F, Feldman B, Gerety D. Granulomatous hepatitis in a patient receiving allopurinol. Gastroenterology. 1972 Jan;62(1):101–104.

- Iqbal U, Siddiqui HU, Anwar H, et al. Allopurinol-induced granulomatous hepatitis: A case report and review of literature. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2017 Sep 8;5(3):2324709617728302.

- Qurie A, Musa R. Allopurinol. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan.