A 59-year-old woman presented to our rheumatology clinic with a six-month history of a symmetric polyarthritis. She initially experienced pain in both knees. As time progressed, she began to notice pain in her ankles, hips, shoulders, hands and feet. She experienced joint stiffness lasting for more than 30 minutes every morning. She also described worsening joint stiffness when she remained inactive for any length of time.

Corticosteroids had been prescribed for her in the past, and she said they did improve her pain by about 50%.

Her primary care provider had ordered lab tests. The test for rheumatoid factor was negative, but an anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) test was positive (nucleolar 1:160 and speckled 1:40).

The patient denied having any skin rashes, mucosal ulcers, renal abnormalities, cytopenias, alopecia, seizures, Raynaud’s phenomenon or thromboembolic events. Prior to the onset of her arthralgias, she denied any upper respiratory, urinary or diarrheal illnesses. She had not traveled outside the U.S.

Past medical history: The patient admitted to having smoked cigarettes in the past (half to a full pack daily for 15–20 years), but she had successfully quit 20 years before. She gave conflicting reports of prior chest X-rays; one of them had shown evidence of emphysema, and a more recent chest X-ray had not shown any lung pathology. There was no history of treatment for emphysema or other chronic pulmonary disease.

Physical exam: The patient’s oxygen saturation was normal, at 98% on room air. Her pulmonary exam was negative for rales, rhonchi and wheezing. Her abdominal exam was negative for tenderness, hepatosplenomegaly or a fluid wave. Upon examination of the extremities, she had clubbing involving all of the digits of her hands. She had swelling around the ankles bilaterally, but there was no palpable synovitis in any of her joints. Her lower legs were tender to palpation from the tibial plateau to the ankles, bilaterally.

Due to the extent of her joint pain, X-rays of the hands, feet and knees were ordered for further evaluation. Rather than repeating a chest X-ray, which had provided conflicting information on two prior occasions, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest was ordered for further evaluation of an underlying pulmonary cause of her digital clubbing. Cardiac causes for her digital clubbing were deemed unlikely, because she had undergone a left heart catheterization in 2013 and no abnormalities were noted during the procedure. Further lab tests were obtained to evaluate her for an inflammatory arthritis.

She was started on 500 mg of nabumetone twice daily for pain control while she was undergoing further evaluation.

Findings: The patient’s comprehensive metabolic profile revealed a glucose level of 103 mg/dL (reference range [RR]: 65–99), urea nitrogen of 14 g/dL (RR: 7–25), creatinine of 0.74 g/dL (RR: 0.5–1.05), estimated glomerular filtration rate of 89 mL/min/1.73m2 (RR: ≥60), sodium 140 mmol/L (RR:135–146), potassium 4.4 mmol/L (RR: 3.5–5.3), chloride 108 mmol/L (RR: 98–110), calcium 8.7 mg/dL (RR: 8.6–10.4), globulin 2.4 g/dL (RR: 1.9–3.7), total bilirubin 0.3 mg/dL (RR: 0.2–1.2), alkaline phosphatase 129 U/L (RR: 33–130), aspartate transaminase 15 U/L (RR: 10–35), alanine aminotransferase 6 U/L (RR: 6–29), total protein 6.2 g/dL (RR: 6.1–8.1) and an albumin level of 3.8 g/dL (RR: 3.8–4.8).

The uric acid level was 5.4 mg/dL (RR: 2.5–7.0). The complete blood count showed a white blood cell count of 5.0 thousand/µL (RR: 3.8–10.8), hemoglobin 12.7 g/dL (RR: 11.7–15.5), hematocrit 38.9% (RR: 35–45) and a platelet count of 322 thousand/µL (RR: 140–400).

Approximately 80% of hypertrophic osteoarthropathy cases are due to a primary or secondary pulmonary malignancy.

The patient’s laboratory workup demonstrated an angiotensin-1-converting enzyme level of 33 U/L (RR: 6–97). The ANA was positive, with both a nucleolar pattern (with a titer of 1:160) and a speckled pattern (with a titer of 1:40). The cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibody test was less than 16 units (RR: <16).

Figure 1: CT of the chest showing a mass in the left lingula.

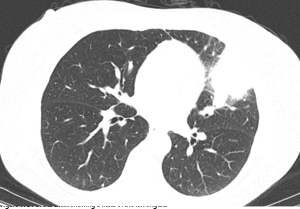

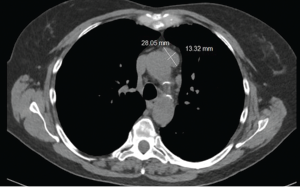

Figure 2: CT of the chest showing a mass in anterior mediastinum.

Serum protein electrophoresis revealed an alpha 1 globulin level of 0.4 g/dL (RR: 0.2–0.3), alpha 2 globulin level of 0.8 g/dL (RR: 0.5–0.9), gamma globulin level of 0.8 g/dL (RR: 0.8–1.7), beta 1 globulin level of 0.4 g/dL (RR: 0.4–0.6), and beta 2 globulin level of 0.3 g/dL (RR: 0.2–0.5).

The sedimentation rate was 29 (RR: ≤30). Her C-reactive protein level was elevated at 15.8 mg/L (RR: <8).

The CT scan of the chest was notable for several findings. An irregular, ill-defined, large, 6×5.6 cm mass was identified in the lingula, with associated adenopathy in the left hilum and anterior mediastinum. Several sub-centimeter noncalcified nodular densities were found in the right lower lobe, but because they were present on prior imaging studies, they were considered to have a benign etiology.

Imaging of the extremities was notable for periostosis involving the tibia and fibula, bilaterally. No effusions, erosions, chondrocalcinosis or destructive process were identified on the imaging studies of the extremities.

The patient was sent for a lung biopsy and positron emission tomography (PET) scan. The PET scan showed a metabolically active site in the left lung compatible with malignancy. Mediastinal and left hilar lymph node metastases were also identified on the PET scan.

Figure 3: X-ray of the right knee showing periostosis of

the fibula and tibia.

Figure 4: X-ray of the left knee showing periostosis of the fibula and tibia.

The lung biopsy demonstrated a non-small cell carcinoma. The patient was diagnosed as having hypertrophic osteoarthropathy (HOA) secondary to a primary lung malignancy. She was referred to an oncologist for further management.

The oncologist ordered magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the patient’s brain, which did not demonstrate metastatic disease. Weekly carboplatin and paclitaxel were initiated, with concurrent radiation.

At the patient’s last encounter with the rheumatology clinic, her arthralgias were not noticeably improving with nabumetone, so she was transitioned to celecoxib. Her arthralgias improved significantly with the medication change.

Discussion

Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy is a rare rheumatologic condition characterized by digital clubbing, periostosis and joint swelling.1 Some patients with HOA may present with a painful arthropathy prior to the onset of clubbing, which can mimic an inflammatory arthritis.2 In the case of our patient, we were initially concerned she might have an inflammatory arthritis due to her elevated C-reactive protein with prominent morning stiffness in the ankles, knees and interphalangeal joints of the hands.

HOA has primary and secondary forms. The primary form is known as pachydermoperiostosis.3 It is a hereditary condition, with a predominance of males afflicted (in a 9:1 ratio) by the disorder.3 In contrast to the secondary forms of HOA, the primary form is more likely to have prominent skin hypertrophy.3

Secondary forms of HOA are of particular concern to rheumatologists, because an underlying disease process may be masked by the HOA. Yao et al. reported in a literature review that approximately 80% of HOA cases are due to a primary or secondary pulmonary malignancy.4 Aside from pulmonary malignancies, many other pathologic processes can contribute to the onset of secondary HOA (see Tables 1 and 2 for a summary, below).

Table 1: Causes of Secondary HOA5

| Pulmonary Diseases | Cardiac Disease | Liver Disease |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer | Infective endocarditis | Cirrhosis |

| Metastasis | Congenital cyanotic disease | Carcinoma |

| Mesothelioma | Biliary atresia | |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | Primary sclerosing cholangitis | |

| Cystic fibrosis | ||

| Chronic infections | ||

| Arteriovenous fistula |

Localized forms of secondary HOA, involving one or two limbs, have also been described in medical literature.5 These localized forms are generally due to marked endothelial injury.5 Aneurysms, infective arteritis, patent ductus arteriosus and hemiplegia are examples of disorders causing these limited forms of HOA.5

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are effective in alleviating pain in most patients with HOA.5 Case reports have been published regarding the use of intravenous bisphosphonates in instances of pain that did not respond to oral NSAIDs.6,7 However, the definitive management of HOA is truly predicated on the treatment of the underlying disease process.5

Table 2: Causes of Secondary HOA, Continued5

| Gastrointestinal Disease | Miscellaneous Conditions |

|---|---|

| Chronic infections | Thymoma |

| Laxative abuse | POEMS syndrome |

| Gastrointestinal polyposis | Thalassemia |

| Cancer | Persistent ductus arteriosus |

| Crohn’s disease | Myelofibrosis |

| Ulcerative colitis | |

| Achalasia |

Ito et al. reported that HOA symptoms may improve with surgical resection of the malignancy.8 Systemic chemotherapy may also improve HOA symptoms.8 The same principle applies to the successful treatment of infectious endocarditis or other secondary cause of HOA.5

Our patient only recently started chemotherapy and radiation treatments for her non-small cell carcinoma, but her signs and symptoms of HOA are expected to improve with successful treatment of the primary pulmonary malignancy.

Conclusion

Our case highlights a rare rheumatologic presentation of hypertrophic osteoarthropathy. An underlying cause of our patient’s clubbing and arthralgias was not readily apparent, and this necessitated an aggressive workup for an underlying cause. This, in turn, led to the discovery of an underlying pulmonary malignancy. This case demonstrates the need for awareness of malignancy masquerading under the guise of arthralgias in patients in whom another etiology cannot be determined in the presence of abnormal clinical findings, such as clubbing.

Theodore Korty, DO, is a second-year rheumatology fellow at Regional Medical Center Bayonet Point, Hudson, Fla.

Adam Grunbaum, DO, is the rheumatology program director at Regional Medical Center Bayonet Point.

References

- Martínez-Lavín M, Matucci-Cerinic M, Jajic I, et al. Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy: Consensus on its definition, classification, assessment and diagnostic criteria. J Rheumatol. 1993 Aug;20(8):1386–1387.

- Martínez-Lavin M, Pineda C. Digital clubbing and hypertrophic osteoarthropathy. In: Rheumatology (2003). Hochberg MC, Silman A, Smolen J, et al. (Eds). London: Mosby; 1763.

- Jajic Z, Jajic I, Nemcic T. Primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy: Clinical, radiologic, and scintigraphic characteristics. Arch Med Res. 2001;32(2):136–142.

- Yao Q, Altman RD, Brahn E. Periostitis and hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy: Report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2009;38(6):458–466.

- Pineda C, Martínez-Lavin M. Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy: What a rheumatologist should know about this uncommon condition. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013 May;39(2):383–400.

- Jayaker BA, Abelson AG, Yao Q. Treatment of hypertrophic osteoarthropathy with zoledronic acid: Case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011 Oct;41(2):291–296.

- Ammital H, Applbaum YH, Vasiliey L, et al. Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy: control of pain and symptoms with pamidronate. Clin Rheumatol. 2004 Aug;23(4):330–332.

- Ito T, Goto K, Yoh K, et al. Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy as a paraneoplastic manifestation of lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2010 Jul;5(7):976–980.