A 36-year-old woman presented at the Johns Hopkins Arthritis Center for a second opinion regarding a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (PsA). One year prior to our evaluation, she had developed pain and stiffness in her hands, feet, knees, ankles, elbows and shoulders. She had mild plaque psoriasis of the scalp and base of the neck, as well as inverse psoriasis of the perianal and genital areas. She had psoriatic nail onycholysis, hyperkeratosis and pitting.

Her past medical history was unremarkable. Her father had PsA that was effectively treated with adalimumab. The patient had been treated with adalimumab 40 mg subcutaneous every 14 days, but had recurrent peripheral arthritis after five months of therapy. She was switched to etanercept 50 mg subcutaneous weekly and standing non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and she experienced some improvement. She was referred to our clinic for further evaluation.

In our clinic, her physical exam revealed several tender and swollen metacarpal, metatarsal and proximal interphalangeal joints, as well as dactylitis of her left fourth toe (see Figure 1, below). There was fingernail pitting. There was a 1 cm erythematous plaque on her scalp with minimal scale, and there were multiple erythematous raised papules with dry surrounding skin in the perianal area. Enthesitis was not present.

Figure 1. Acute dactylitis of the left fourth and right third toes.

Laboratory studies were unremarkable, with a negative human leukocyte antigen B27 (HLA-B27) test and normal inflammatory markers. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the sacroiliac joints did not show sacroiliitis.

Dactylitis & enthesitis are both regarded as signs of PsA disease severity. Dactylitis is associated with joint erosions. Enthesitis is associated with worse disease & radiographic damage in psoriatic arthritis.

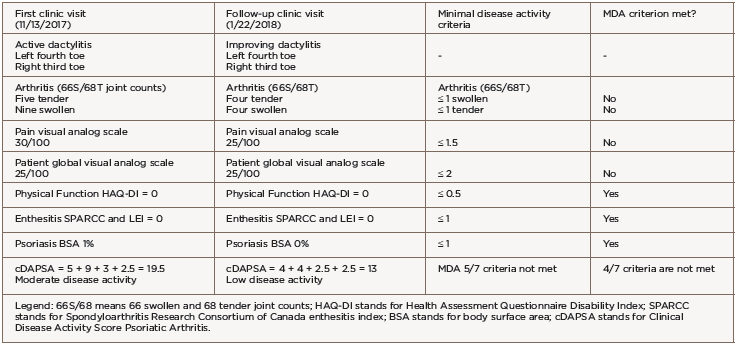

We diagnosed her with PsA on the basis of inflammatory joint pain, a current history of psoriasis, nail dystrophy typical of psoriasis, negative rheumatoid factor and dactylitis. She had a total score of 5 per the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR); a classification of psoriatic arthritis is made for a score of 3 or greater.

Given the patient’s ongoing disease activity, we added sulfasalazine 1,000 mg twice daily to her regimen and continued etanercept. We avoided methotrexate and leflunomide due to the patient’s desire for future pregnancy. Her peripheral arthritis improved, and the dactylitis resolved (see Figure 2, below).

Figure 2. Improving dactylitis at the left fourth and right third toes.

After 13 months of treatment with sulfasalazine, we had to stop the medication due to drug-induced transaminitis. The patient’s psoriasis and arthritis worsened with etanercept monotherapy.

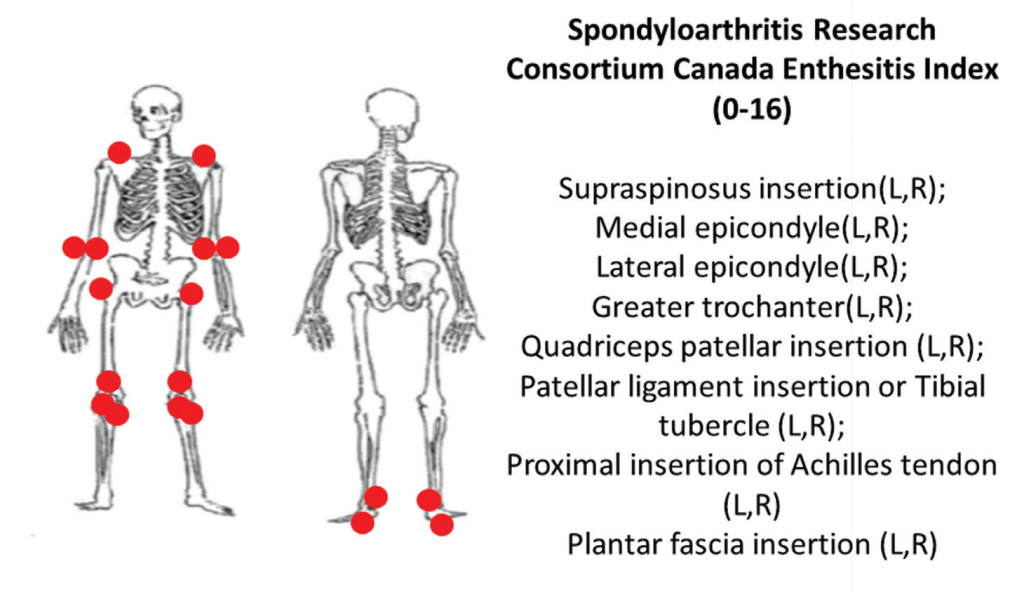

She was transitioned to certolizumab pegol 200 mg subcutaneous every 14 days with adequate disease control. However, after 12 months of therapy, she developed breakthrough peripheral arthritis with a clinical disease activity psoriatic arthritis score (DAPSA) of 19.5 (corresponding to moderate disease activity), scalp and genital psoriasis (on a total body surface area of 1%), as well as acute left fourth toe and right third toe dactylitis (see Table 1).

The patient did not meet PsA minimal disease activity criteria (MDA) due to five tender and nine swollen joints, a pain score of 30/100 and a patient global assessment score of 25/100. Given the failure of three tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, we switched treatment to 90 mg of subcutaneous ustekinumab every 12 weeks, with loading doses at Days 0 and 28.

We evaluated the patient in our clinic for follow-up six weeks after the initial ustekinumab dose. Her psoriasis and peripheral arthritis had resolved. She demonstrated clinical improvement of the dactylitis and decreased erythema, swelling and tenderness (see Table 2). The patient’s clinical DAPSA was now 13, corresponding to low disease activity, but her PsA activity again did not meet MDA criteria due to four swollen/tender joints of two dactylitic toes, a pain score of 25/100 and a patient global assessment score of 25/100 (see Table 1).

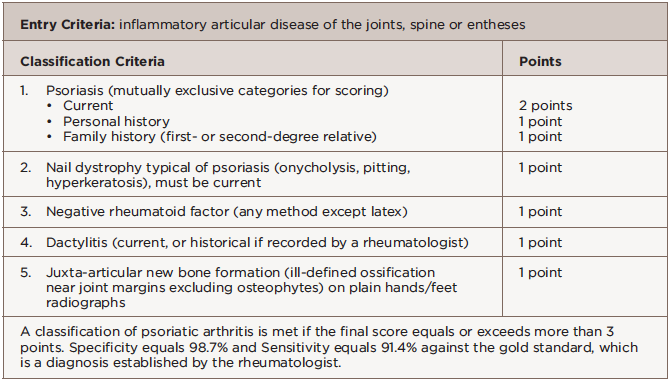

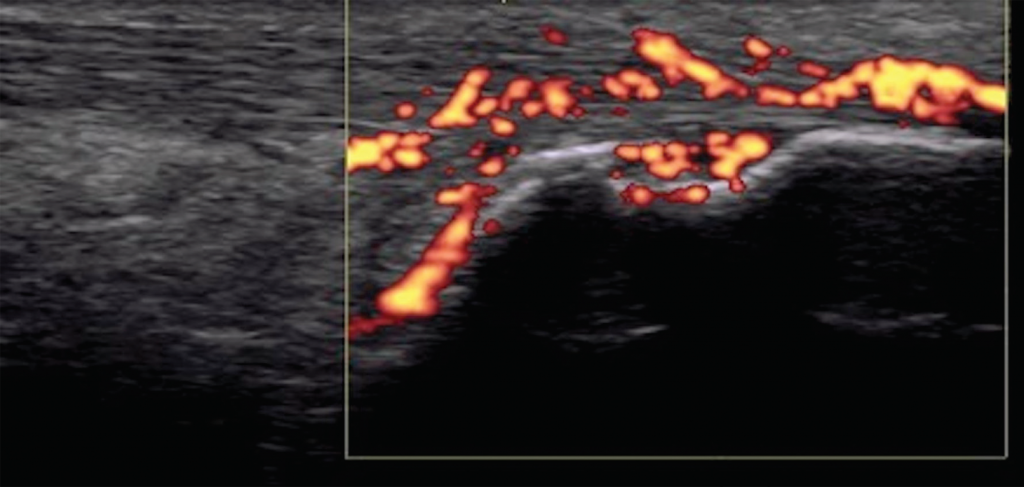

Musculoskeletal ultrasound of her feet revealed hypoechoic collections surrounding the extensor tendons of these dactylitic digits as well as at the interphalangeal joints with Doppler enhancement, consistent with tenosynovitis and synovitis (see Figure 3). We saw no erosions. Radiographs showed slight spurring of the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints and were otherwise unremarkable (see Figure 4). We continued ustekinumab and treated persistent toe dactylitis with local corticosteroid injections.

Figure 3. Interphalangeal (IP) toe joint with extensor tenosynovitis and IP synovitis with Doppler enhancement.

Figure 4. Bilateral feet radiographs appear normal except for subtle spurring at the bilateral first proximal interphalangeal joints.

Should ustekinumab augmented by local corticosteroid injection fail to adequately control disease after the third 90 mg dose (at 16 weeks of treatment), we plan to switch to a biologic with a different mechanism of action.

Psoriatic Arthritis Described

PsA is a complex rheumatologic disease that manifests in multiple individual patterns of musculoskeletal and skin involvement. Its hallmark features include inflammatory musculoskeletal disease in the presence of active or historical psoriasis skin inflammation, or a genetic predisposition to psoriasis through family history in a first- or second-degree relative. Psoriasis prevalence in the U.S. is 2%, and roughly one in three people with psoriasis develop PsA.1

Figure 5. Dactylitis with flexor tenosynovitis and tendon Doppler enhancement.

A study from Toronto recently described the symptoms experienced by people with psoriasis prior to a PsA diagnosis: joint pain, fatigue and stiffness.2 Classification criteria for PsA are based on clinical evaluation and exclusion of rheumatoid arthritis (see Table 2). The presence of nail psoriasis and dactylitis increase specificity for a PsA classification.

Psoriatic Dactylitis & Enthesitis

Dactylitis and enthesitis are established, disease-specific manifestations in PsA. Each affect roughly half of the patients over their lifetime, and they are associated with increased disease burden and worse patient outcomes compared to patients who do not experience these manifestations. Pathophysiology of dactylitis and enthesitis are objects of intense study, as are their longitudinal quantification and measurement.

Dactylitis is defined as inflammation affecting all anatomical layers of a digit. Acute dactylitis is tender. Permanent damage has been demonstrated in digital joints affected by dactylitis, so it has a prognostic role as a sign of disease severity. In the CASPAR classification study, dactylitis increased the odds of PsA by 5.5–20 (historical dactylitis 5.5 and 95% CI 1.8–17; acute dactylitis 20 and 95% CI 5.9–67).

Enthesitis is defined as inflammation localized to the insertion sites of tendons and ligaments at the bony surface. The human body has more than 100 entheses; examples include the Achilles tendon insertion at the calcaneus, the annulus fibrosus insertions at the vertebral bodies, the sacroiliac joints and the flexor tendon insertions of the phalanges.

Enthesitis is a prominent feature of PsA and is included as part of the stem for the 2006 CASPAR criteria.3 Enthesitis leads to greater overall disease burden with poorer functional status, greater patient-reported pain and fatigue, and impairment of work and activities.4

Epidemiology

A diagnosis of dactylitis is based on clinical appearance and is best described as a sausage digit (see Figures 1 and 2). Dactylitis occurs in 40% of adult patients with established PsA.5 Examination of the feet is critical in diagnosing dactylitis because it can occur equally in fingers and toes. In the U.S. multicenter CORRONA PsA registry, prevalence of dactylitis in a cross-sectional PsA sample measured 15%.4 Dactylitis can occur in patients who are already taking PsA treatments, and when that happens, it is a sign of active or poorly controlled psoriatic disease.

The prevalence of enthesitis in patients with PsA runs between 25% and 53% when defined by physical exam findings alone.6 When identified by imaging, the prevalence is much higher, likely because the nearness of entheses to joints may result in clinical misdiagnosis of enthesitis as synovitis or fibromyalgia tender points.

Enthesitis may also be asymptomatic or subclinical. Young age, increased disease duration, HLA-B27 alleles, active peripheral joint disease and elevated body mass index are risk factors for developing enthesitis.6-9

Pathophysiology

Dactylitis is digital inflammation affecting multiple superimposed, anatomical layers. There is uncertainty about the initial lesion in dactylitis. In a systematic literature review of ultrasound and MRI findings in dactylitis, the most commonly seen pathologies were flexor tenosynovitis and joint synovitis (90%).9 In a high-resolution MRI study of dactylitic fingers, additional findings included collateral ligament enthesitis (75%), flexor tendon pulley/flexor sheath microenthesopathy (50%), bone marrow edema and diffuse extracapsular soft tissue edema.11

We can conclude dactylitis is a quantitatively and qualitatively heterogeneous process distinguished by inflammation crossing anatomical structures, and there is significant overlap with enthesitis and synovitis (see Figures 3 and 5). Clinical diagnosis of dactylitis may identify an already advanced inflammatory process. This may explain the association of clinical dactylitis with joint erosions and damage in the affected digits, and as an overall prognostic indicator for aggressive disease.

Enthesitis is a hallmark of PsA, but the exact reason why this manifestation occurs remains unclear. Enthesitis may occur in healthy individuals due to mechanical stress (e.g., Achilles tendinitis, tennis elbow, etc.), but it occurs more frequently and diffusely in patients with PsA. In PsA, inflammatory changes of the entheses mostly involve the fibrocartilaginous, rather than membranous, attachments.12 Some researchers postulate the trigger for entheseal inflammation is a mechanical insult, followed by an excessive inflammatory reaction driven by the innate immune response.

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), the main enzymatic product of cyclo-oxygenases, is a vital early mediator of inflammation. PGE2 induces vasodilation, which could facilitate neutrophil migration from the bone marrow to the neighboring entheseal compartment. Thereafter, interleukin (IL) 17, IL-23 and TNF-α are instrumental in augmenting inflammation.6

The end result of enthesitis? New bone formation, tendon integrity disruption and neovascularization, features that can be quantified using ultrasonography.

Enthesophytes are caused by excessive local apposition of periosteal bone to entheseal sites. To correlate it clinically, entheseal inflammation of the anterior longitudinal spinal ligament results in syndesmophytes with spinal ankylosis, and entheseal inflammation of the plantar fascia results in calcaneal spurs.6

Assessing Dactylitis

Dactylitis diagnosis is clinical. An examination sees fusiform swelling of fingers or toes with associated variable erythema and locally increased temperature, and tenderness in the acute phase. Differential diagnosis includes infection, crystalline disease and sarcoidosis.

The only PsA-specific dactylitis index is the Leeds enthesitis index, performed with a small measurement tool (the Leeds dactylometer) and scored as a weighted sum of dactylitic digits upon assessment of all 20 digits.13 A digit is defined as dactylitic if its circumference measures 10% higher than the contralateral digit/or reference norms.

For scoring, the weights applied are 0–1 (i.e., 0 is not tender, 1 is tender) for the basic Leeds index, and 0–3 (i.e., 0 has no tenderness and 1–3 indicates increasingly higher degrees of tenderness) for the initial index. The Leeds index counts only acute dactylitis.

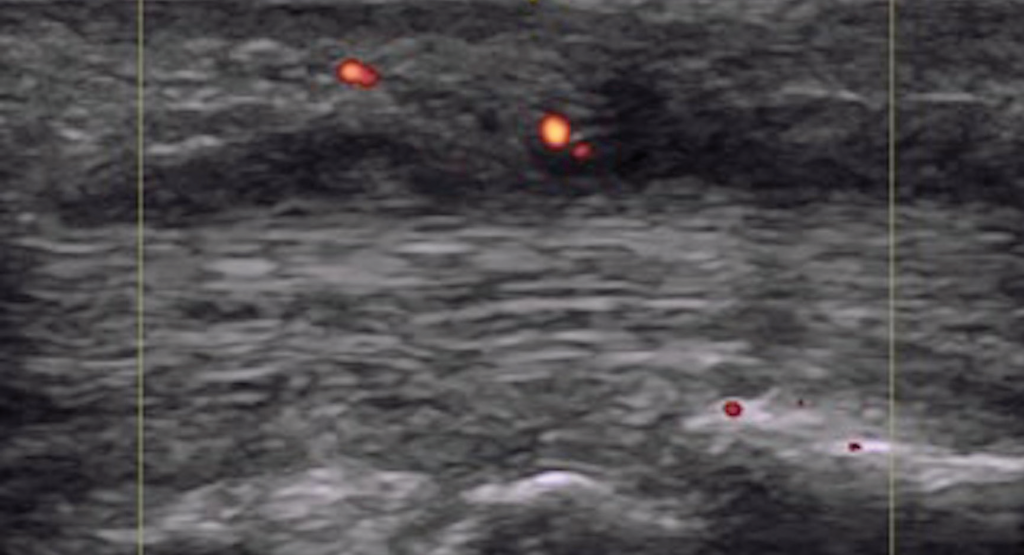

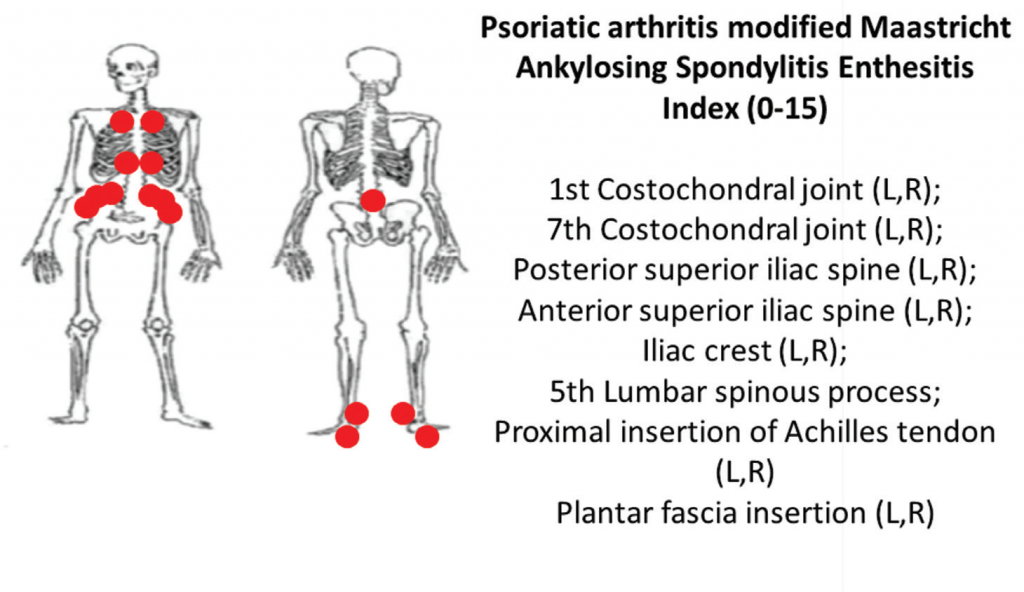

6A: The Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada clinical enthesitis index.

6B: The PsA-modified Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis clinical enthesitis index (PsA MASES).z

Dactylitis can also be demonstrated on ultrasound and MRI, as described above.

Assessing Enthesitis

Multiple clinical and ultrasound enthesitis indices exist or are in development. Although clinical enthesitis indices are the most feasible to perform, they are also the most difficult to align with the true pathophysiological process underlying enthesitis because they rely on the assumption that tenderness to pressure is representative of PsA entheseal inflammation. Confounding factors for PsA enthesitis on clinical or imaging assessment include pain attributable to anatomical structures in proximity to entheses, degenerative processes, physiological enthesial complex aging and overuse/injury, among others.

Two comprehensive clinical enthesitis indices include the Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada enthesitis index (SPARCC) and the PsA modified Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score (MASES). Both have been used in PsA clinical trials. SPARCC assesses entheses that are predominantly peripheral by tenderness to standardized pressure applied on examination of 18 sites. The SPARCC score range is 0–16, and higher scores indicate more entheseal sites are tender.

Using the same examination technique, the PsA-modified MASES index assesses axial and lower extremity entheses at 15 sites with a score range of 0–15. Higher PsA modified MASES scores indicate more entheseal sites involved (see Figures 6A and 6B).

Imaging studies, particularly ultrasound, are more sensitive at detecting peripheral enthesitis than clinical exams, and they can identify subclinical entheseal involvement as well as characterize anatomical changes more specific to an inflammatory disease. Both inflammatory changes (e.g., tendon thickening and hypoechogenicity near insertion, bursitis, Doppler enhancement, etc.), as well as damage changes (e.g., bone erosions, enthesophytes, etc.) can be seen (see Figure 7).12

Prognostic Value

Dactylitis and enthesitis are both regarded as signs of PsA disease severity. Dactylitis is associated with joint erosions.14 Enthesitis is associated with worse disease and radiographic damage in psoriatic arthritis.9 Depending on location (e.g., the Achilles tendon), dactylitis can cause disability and adversely impact a patient’s life in addition to other PsA manifestations.

Treatment

To date, no studies have been sufficiently powered to investigate the treatment of dactylitis and enthesitis, but several studies have reported them as secondary endpoints. The Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommend corticosteroid injections and conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) as first-line therapy for dactylitis, and NSAIDs and physiotherapy as first-line therapy for enthesitis. In patients who fail to respond, these steps are followed by biologics (e.g., TNF inhibitors).15,16

NSAIDs work by downregulating PGE2 production, an early mediator of entheseal inflammation. Ultrasonography studies have shown NSAIDs decrease vasodilation and inflammation at entheses.17 Note: Once enthesitis becomes chronic, it is anecdotally harder to treat and less responsive to NSAIDs.

Conventional synthetic DMARDs are generally not efficacious for enthesitis, and switching to a biologic therapy as a next step is reasonable. TNF inhibitors have shown benefit for both axial and peripheral enthesitis in a variety of studies (though they were not designed to look at this as a primary outcome). Infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab and certolizumab are all viable options, though head-to-head comparisons have not been made between these drugs for clinical dactylitis and enthesitis.18-22

Figure 7. Achilles tendon enthesitis with active Doppler; erosion of calcaneus.

MRI studies of patients with spondyloarthritis (predominantly of the ankylosing spondylitis subset) have shown improvement of peripheral joint, sacroiliac joint and vertebral body peri-entheseal osteitis with TNF inhibitors.23 Secukinumab, ixekizumab (which are anti-IL-17A inhibitors) and ustekinumab (an anti-IL12/23 inhibitor) have also shown efficacy in both clinical dactylitis and enthesitis.24-26

GRAPPA recommends switching to alternate mechanisms of action if TNF inhibitors fail to provide adequate relief. Apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, has been shown to have some efficacy in axial enthesitis (MASES). Apremilast decreases the production of several cytokines involved in entheseal inflammation (IL-17A, IL-23 and TNF-α), and also decreases neutrophil migration to the entheseal complex. A study of 504 patients showed improvement in axial enthesitis in about half of study participants by 12 months of therapy.27 More studies are needed to determine how effective apremilast is for peripheral enthesitis and for dactylitis.

Tofacitinib, a JAK inhibitor approved for treating PsA, showed numerical benefits in enthesitis and dactylitis, which could not be tested for statistical significance in the primary clinical trials due to the hierarchical outcome testing procedure.28,29

Knowledge Gaps & Future Developments

Enthesitis measurement remains an area of intense research. Although diagnosis and follow-up are largely clinical due to feasibility considerations, evidence exists that ultrasound and/or MRI assessments have the potential to more directly measure the pathophysiological changes induced by the PsA disease process.12

In clinical trials, only a portion of patients with dactylitis and/or enthesitis responded to the agents noted above. The numbers of new onset and recurrent dactylitis and enthesitis in clinical trials are of great relevance for clinical practice and treatment guidelines, but they are not commonly reported. None of these therapies have been compared in head-to-head analyses, and none have been specifically studied for enthesitis or dactylitis as primary efficacy endpoints. Studies using multiple methods of assessment that capitalize on independently capturing definite underlying pathology in enthesitis and dactylitis are needed to improve our evidence base for treating these PsA-specific manifestations.

Samantha C. Shapiro, MD, completed her training at the Johns Hopkins Division of Rheumatology in June 2018. She is now an attending physician at The University of Texas at Austin, Dell Medical School.

Jemima Albayda, MD, is an assistant professor of medicine and director at the Musculoskeletal Ultrasound and Injection Clinic in the Division of Rheumatology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore.

Ana-Maria Orbai, MD, MHS, is an assistant professor of medicine and director of the Psoriatic Arthritis Program in the Division of Rheumatology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore.

Disclosures

Dr. Orbai is a Jerome L. Greene Foundation Scholar and is supported in part by a research grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number P30-AR070254 (Core B), a Rheumatology Research Foundation Scientist Development award and a Staurulakis Family Discovery award. All statements in this report, including its conclusions, are the opinions of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of NIH, NIAMS or the Foundation. Dr. Orbai has received research funding from Celgene Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Horizon and Pfizer. Dr. Orbai was an advisor (Advisory Board participant) for Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB.

References

- Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Papp KA, et al Prevalence of rheumatologist-diagnosed psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis in European/North American dermatology clinics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Nov;69(5):729–735.

- Eder L, Polachek A, Rosen CF, et al. The development of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis is preceded by a period of nonspecific musculoskeletal symptoms: A prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Mar;69(3):622–629.

- Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, et al. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Aug;54(8):2665–2673.

- Mease PJ, Karki C, Palmer JB, et al. Clinical characteristics, disease activity and patient-reported outcomes in psoriatic arthritis patients with dactylitis or enthesitis: Results from the Corrona Psoriatic Arthritis/Spondyloarthritis Registry. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017 Nov;69(11):1692–1699.

- Gladman DD, Ziouzina O, Thavaneswaran A, et al. Dactylitis in psoriatic arthritis: Prevalence and response to therapy in the biologic era. J Rheumatol. 2013 Aug;40(8):1357–1359.

- Schett G, Lories RJ, D’Agostino MA, et al. Enthesitis: From pathophysiology to treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017 Nov 21;13(12):731–741.

- Polachek A, Li S, Chandran V, et al. Clinical enthesitis in a prospective longitudinal psoriatic arthritis cohort: Incidence, prevalence, characteristics and outcome. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017 Nov;69(11):1685–1691.

- Polachek A, Cook R, Chandran V, et al. The association between HLA genetic susceptibility markers and sonographic enthesitis in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 May;70(5):756–762.

- Polachek A, Cook R, Chandran V, et al. The association between sonographic enthesitis and radiographic damage in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017 Aug 15;19(1):189.

- Bakewell CJ, Olivieri I, Aydin SZ, et al. Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of psoriatic dactylitis: Status and perspectives. J Rheumatol. 2013 Dec;40(12):1951–1957.

- Tan AL, Fukuba E, Halliday NA, et al. High-resolution MRI assessment of dactylitis in psoriatic arthritis shows flexor tendon pulley and sheath-related enthesitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015 Jan;74(1):185–189.

- Kaeley GS, Eder L, Aydin SZ, et al. Enthesitis: A hallmark of psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018 Jan 6.

- Helliwell PS, Firth J, Ibrahim GH, et al. Development of an assessment tool for dactylitis in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005 Sep;32(9):1745–1750.

- Brockbank JE, Stein M, Schentag CT, et al. Dactylitis in psoriatic arthritis: A marker for disease severity? Ann Rheum Dis. 2005 Feb;64(2):188–190.

- Gossec L, Smolen JS, Gaujoux-Viala C, et al. European league against rheumatism recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Jan;71(1):4–12.

- Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, et al. Group for research and assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016 May;68(5):1060–1071.

- Mouterde G, Aegerter P, Correas JM, et al. Value of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography for the detection and quantification of enthesitis vascularization in patients with spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014 Jan;66(1):131–138.

- Sterry W, Ortonne J-P, Kirkham B, et al. Comparison of two etanercept regimens for treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: PRESTA randomised double blind multicentre trial. BMJ. 2010 Feb 2;340:c147.

- Kavanaugh A, McInnes IB, Mease P, et al. Clinical efficacy, radiographic and safety findings through 5 years of subcutaneous golimumab treatment in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: Results from a long-term extension of a randomised, placebo-controlled trial (the GO-REVEAL study). Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 Sep;73(9):1689–1694.

- Antoni C, Krueger GG, De Vlam K, et al. Infliximab improves signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis: Results of the IMPACT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005 Aug;64(8):1150–1157.

- Mease PJ, Van Den Bosch F, Sieper J, et al. Performance of 3 enthesitis indices in patients with peripheral spondyloarthritis during treatment with adalimumab. J Rheumatol. 2017 May;44(5):599–608.

- Mease PJ, Fleischmann R, Deodhar AA, et al. Effect of certolizumab pegol on signs and symptoms in patients with psoriatic arthritis: 24-week results of a Phase 3 double-blind randomised placebo-controlled study (RAPID-PsA). Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 Jan;73(1):48–55.

- Marzo-Ortega H, McGonagle D, O’Connor P, et al. Efficacy of etanercept in the treatment of the entheseal pathology in resistant spondylarthropathy: A clinical and magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthritis Rheum. 2001 Sep;44(9):2112–2117.

- McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriatic arthritis (FUTURE 2): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015 Sep 19;386(9999):1137–1146.

- Mease PJ, Van Der Heijde D, Ritchlin CT, et al. Ixekizumab, an interleukin-17A specific monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis: Results from the 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled and active (adalimumab)-controlled period of the phase III trial SPIRIT-P1. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Jan;76(1):79–87.

- McInnes IB, Kavanaugh A, Gottlieb AB, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 1 year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled PSUMMIT 1 trial. Lancet. 2013 Aug 31;382(9894):780–789.

- Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Gomez-Reino JJ, et al. Treatment of psoriatic arthritis in a phase 3 randomised, placebo-controlled trial with apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 Jun;73(6):1020–1026.

- Gladman D, Rigby W, Azevedo VF, et al. Tofacitinib for psoriatic arthritis in patients with an inadequate response to TNF inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 19;377(16):1525–1536.

- Mease P, Hall S, FitzGerald O, van der Heijde D, Merola JF, Avila-Zapata F, Cieślak D, Graham D, Wang C, Menon S, Hendrikx T, Kanik KS, et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 19;377(16):1537–1550.