Dermatomyositis is an uncommon autoimmune condition involving skeletal muscle characterized by subacute onset of progressive weakness, intramuscular inflammatory infiltrates and the presence of myositis-specific autoantibodies.1 Immune-mediated myopathies may exert some pathogenic effects on the muscle tissue by targeting the microvasculature.1 Capillary inflammation, fragility and loss may contribute to heightened bleeding events in these patients.

Here, we discuss a case of acute hemorrhagic dermatomyositis, a rare, highly morbid complication of dermatomyositis.

Case History

A previously healthy, 66-year-old man presented with gradual onset of painfully swollen and stiff upper and lower extremities, diffuse rash and progressive weakness. He worked as a custodian and reported that he’d had difficulty lifting trash cans and climbing stairs for the past two months. He also reported that during the preceding two weeks he’d been struggling to reach for his seatbelt and had difficulty getting in and out of his truck. He ultimately presented for medical attention because he could no longer ambulate independently.

Over the past year, he had experienced fatigue, episodic dizziness, daytime and nighttime sweats, reduced appetite, trouble swallowing and unintentional weight loss. He lived alone and had not seen a medical provider for more than five decades until the previous month, following an emergency department visit. He had a 45-pack-year smoking history and a remote history of heavy alcohol use.

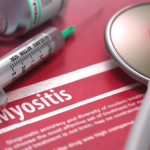

Vital signs in the emergency department were normal. An examination revealed a chronically ill-appearing man in no acute distress. He had multiple, erythematous, pearly nodules up to four centimeters in diameter on his left forehead, right eyebrow and left neck, suggestive of basal cell carcinoma (see Figure 1).

An erythematous maculopapular poikilodermic rash was present on his scalp, forehead, cheeks, neck, chest, upper back, upper arms, and dorsal aspects of his metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints of his digits. He had painful periungual erythema of his fingernails.

His neurologic exam was notable for symmetric proximal weakness, with his upper extremities being weaker than his lower extremities. Manual muscle testing revealed the following Medical Research Council (MRC) grades: cervical flexion and extension 5/5, deltoids 2/5, biceps and triceps 3/5, wrist extensors and flexors 5/5 apart from 4+/5 left wrist extension, finger abduction 4+/5, finger flexion 5/5, hip flexion 3/5, quadriceps 5-/5, hamstrings 4+/5, anterior tibialis 5/5, gastrocnemius 5/5.

Figure 1. The physical examination revealed multiple, large, erythematous pearly nodules suggestive of basal cell carcinoma, as shown on his left temple, and a diffuse poikilodermic rash (maroon arrows).

He had no ocular, facial or bulbar weakness or sensory deficits. His deep tendon reflexes were trace at the biceps, brachioradialis and Achilles tendons. His patellar reflexes were 3+ with crossed adduction in both limbs. The remainder of the exam was unremarkable.

Emergency department laboratory testing from four weeks before was notable for normal renal function, normal blood counts, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 313 IU/L (normal: 10–50 IU/L) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 124 IU/L (normal: 10–44 IU/L).

At follow-up with his primary care provider four days later, his liver transaminases were persistently elevated: AST 301 IU/L, ALT 134 IU/L and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 116 U/L (normal: 40–129 U/L). Other abnormally elevated laboratory studies at this visit included C-reactive protein (CRP) 30 mg/L, anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) 1:320 with speckled pattern, anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA) 54 U, anti-mitochondrial antibody (AMA) 43.8 U, rheumatoid factor (RF) 57.8 IU/mL. Lyme IgG/IgM and Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever IgM screening tests fell within equivocal range.

Even with prompt recognition, acute hemorrhagic myositis can cause abrupt hemodynamic collapse & rapid progression to death.

His primary care physician consulted a hepatologist, due to concern for autoimmune hepatitis, and initiated empiric doxycycline with concern for tick-borne illness.

A recheck of laboratory studies during the current presentation revealed AST 191 U/L (normal: 15–41 U/L), ALT 76 U/L (normal: 17–63 U/L), ALP 112 U/L (normal: 24–110 U/L), albumin 1.8 g/dL (normal: 3.5–4.8 g/dL), aldolase 17.8 U/L (normal: <7.7 U/L), and peak creatine kinase (CK) 2,848 U/L (normal: 30–220 U/L). Creatinine and complete blood count tests were within normal limits. His CRP (2.79 mg/dL) and ferritin (735 ng/mL) were elevated, but his erythrocyte sedimentation rate was within the normal range.

Positive serologies included ANA 1:2560 with cytoplasmic speckling, AMA 39.9 U, RF 88 IU/mL, and anti-ribonuclear protein (RNP) 193 AU/mL. The MyoMarker Panel 3 was notable for an elevated anti-transcription intermediary factor 1-γ (TIF1-γ) at 126 U (normal: <20 U).

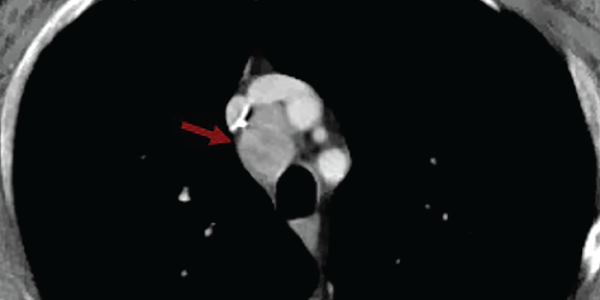

A contrast computerized tomography (CT) scan of his chest, abdomen and pelvis revealed numerous enlarged and heterogeneously enhancing mediastinal and right hilar lymph nodes (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. A contrasted CT scan of the chest shows numerous pathologic mediastinal and right hilar lymph nodes (maroon arrow).

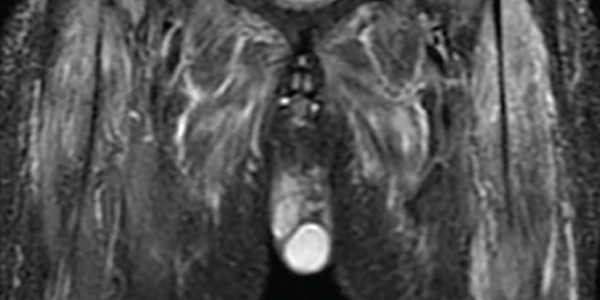

Magnetic resonance imaging scan with myositis protocol of his lower extremities showed extensive symmetric T2 hyperintense signal involving the bilateral thigh and pelvis musculature with evidence of subcutaneous and perifascial edema consistent with myositis (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. An MRI myositis protocol of the lower extremities with extensive, symmetric edema-like T2 signal of both thighs and the pelvis musculature.

Electromyography revealed abundant spontaneous activity in the form of fibrillation potentials and positive sharp waves in the deltoid and biceps brachii; it showed myopathic motor unit action potentials with early recruitment, consistent with an inflammatory myopathy.

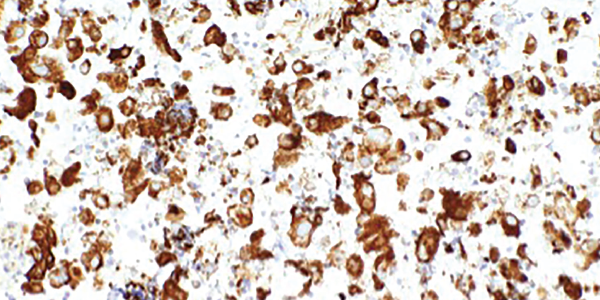

A videofluoroscopic swallow study showed no oropharyngeal dysphagia. He underwent endobronchial ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of multiple lymph nodes. Rare tumor cells were present, with immunohistochemical testing positive for cytokeratin 7, suggestive of adenocarcinoma, and weakly positive for thyroid transcription factor 1, suggestive of a lung primary adenocarcinoma (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. An ultrasound-guided, fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the mediastinal lymph nodes shows rare tumor cells. Immunohistochemical testing revealed the presence of cytokeratin 7 and thyroid transcription factor 1.

Next-generation sequencing was remarkable for missense mutations of NRAS, which are more commonly found in adenocarcinomas with a history of tobacco use, and TP53, which can be seen in a number of malignancies including lung cancers.2,3

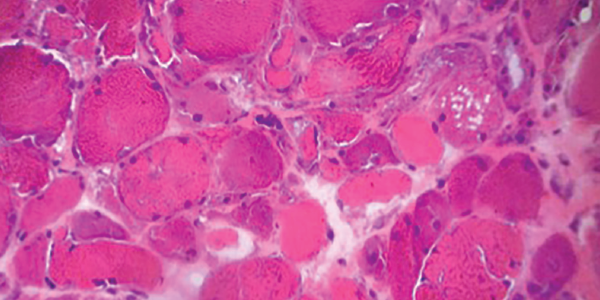

Left forehead and right eyebrow lesion shave biopsies showed nodular and infiltrative pattern basal cell carcinoma, respectively. A right deltoid muscle biopsy demonstrated myopathic changes, fiber necrosis, fiber atrophy and minimal inflammatory cells, with no evidence of hemorrhage, granulomas or vasculitis (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. H&E staining of a muscle biopsy demonstrates myopathic changes, fiber necrosis and fiber atrophy, albeit a paucity of inflammatory cells.

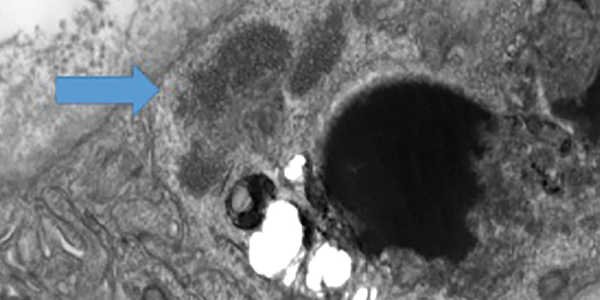

MHC-I immunohistochemical staining showed patchy sarcolemmal up-regulation and an increased alkaline phosphatase staining pattern, consistent with an immune-mediated myopathic process. Electron microscopy of the muscle sample showed tubuloreticular inclusions (see Figure 6).

Figure 6 . Electron microscopy of a muscle biopsy shows tubuloreticular inclusions (blue arrow).

Our patient was diagnosed with dermatomyositis and began therapy with 1 mg/kg of oral prednisone daily on hospital day (HD) 2.

On HD 5, he started to experience intermittent, deep, throbbing inguinal pain on the left side. Examination of the area revealed no cutaneous abnormalities, palpable mass, tenderness to palpation or significant pain with passive range of motion.

On HD 7, his hemoglobin dropped to 6.9 g/dL, and his blood pressure acutely dropped to 74/36 mmHg. Upon review of his laboratory studies, his CK had risen from 793 U/L on HD 5 to 1,100 U/L on HD 6 and to 1,729 U/L on HD 7. Prothrombin time and prothrombin INR were within normal range. Partial thromboplastin time was minimally elevated.

An ultrasound of his left groin showed a 6.9×2.3×4.4 cm anechoic collection most suspicious for a hematoma. A CT scan of his abdomen and pelvis with and without contrast revealed multiple intramuscular hematomas in the left psoas, left abductor magnus/pectineus and left rectus femoris.

His blood pressure normalized with blood products and intravenous fluids. With ongoing sensation of dysphagia and concern for severe features of dermatomyositis, treatment began with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) 10% 0.5 g/kg per day on HD 9 for four days.

Notably, he had 10 doses of prophylactic subcutaneous heparin from HD 2 to HD 6. The hematomas were managed conservatively, and he recovered from the acute episode with supportive care. He received systemic chemotherapy for adenocarcinoma of presumed lung origin, started a slow oral prednisone steroid taper from 1 mg/kg per day, and was discharged to a long-term rehabilitation facility.

As an outpatient, he did not tolerate aggressive treatments with intravenous chemotherapy, suffering from recurrent pulmonary infections that left him with an oxygen requirement and mostly bedbound. In view of this, he transitioned to a lower potency oral chemotherapeutic agent given his overall poor prognosis. Due to difficulty coordinating treatments and his ongoing health decline, he received no further IVIG. No additional hemorrhagic events were reported. Sadly, the patient died within a few months of discharge.

Discussion

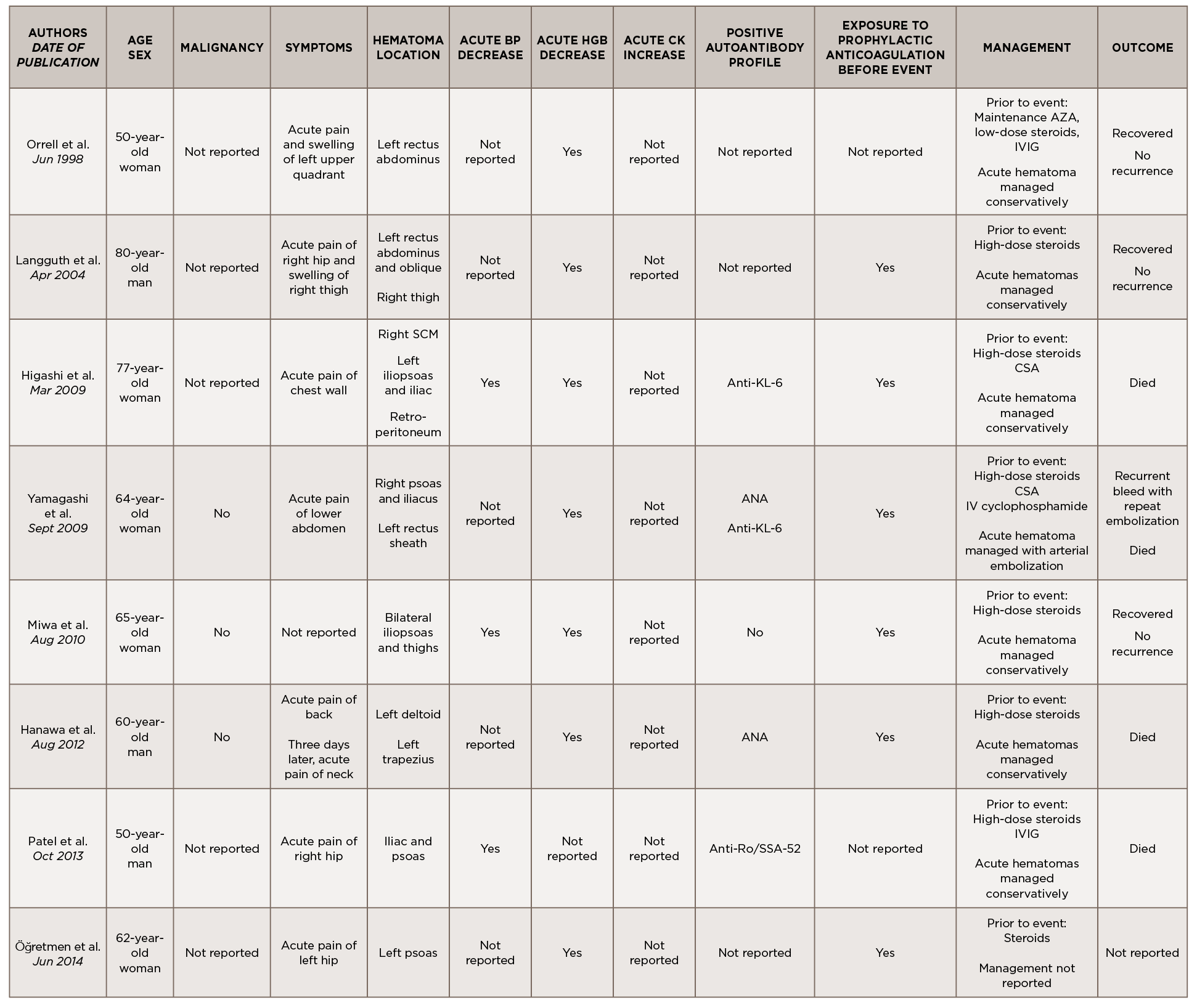

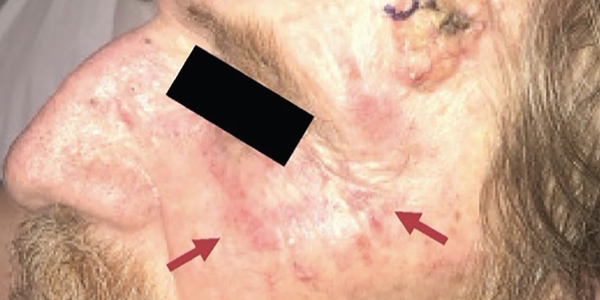

This is a case of anti-TIF1-γ positive paraneoplastic acute hemorrhagic dermatomyositis, an uncommon yet severe complication of dermatomyositis. As shown in Table 1, at least 16 adult cases of acute hemorrhagic dermatomyositis have been reported.4-18 The majority of these patients were middle aged, with approximately equal distribution among men and women.

Table 1

Legend: ANA, anti-nuclear antibody; AMA, anti-mitochondrial antibody; ASMA, anti-smooth muscle antibody; Anti-TIF1-γ, anti-transcription intermediary factor 1-γ; AZA, azathioprine; BP, blood pressure; CK, creatine kinase; CSA, cyclosporin A; CYC, cyclophosphamide; Hgb, hemoglobin; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; RF, rheumatoid factor; RNP, ribonucleoprotein; SCM, sternocleidomastoid; VS, vital signs

Although the past medical histories and clinical contexts differ slightly among these patients, only one was reported as having a concurrent malignancy.18 Most were newly diagnosed with dermatomyositis and subsequently developed atraumatic painful intramuscular hematomas, some of which were hemodynamically significant. All events occurred following administration of systemic glucocorticoids, and most events occurred following prophylactically or therapeutically dosed anticoagulation.

Some patients were treated with IVIG either before or after the hemorrhagic event, and a few were treated with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) either before, during or after acute hematoma formation.

Comprehensive autoimmune serologies were either not performed or not described in a majority of these case reports; of those reported, a positive ANA was seen in four patients, Sjögren’s syndrome-related antigen A (SSA) 52 kDa antibody in two patients, and Krebs von den Lungen 6 (KL-6) antibody in two patients. Apart from our case, only two other reports identified the presence of myositis-specific autoantibodies.14,16

Even with prompt recognition, acute hemorrhagic myositis can cause abrupt hemodynamic collapse and rapid progression to death. Aside from the inherent microvasculopathy of dermatomyositis, nearly all patients reported in the literature received either prophylactic or therapeutic doses of anticoagulation ahead of having a hemorrhagic event; this finding underscores the complex safety concerns surrounding anticoagulation in often immobile patients with underlying malignancies.

All patients reported in the literature seem to have developed hematomas while receiving systemic glucocorticoids and often did not respond to an escalation in steroid dose, calling into question the utility of immunosuppression in this clinical context.

Apart from vital sign changes and a decline in hemoglobin, the earliest diagnostic clue appears to be the acute onset of localized pain, which can be out of proportion to exam.

Apart from vital sign changes and a decline in hemoglobin, the earliest diagnostic clue appears to be the acute onset of localized pain, which can be out of proportion to exam. As in our case, a rapid rise in CK could also herald the presence of an intramuscular hematoma. Further research is needed to clarify whether the presence of certain autoantibodies, especially myositis-specific autoantibodies, confer a higher risk of developing hemorrhagic complications; this ultimately may help further define the clinical phenotypes associated with myositis-specific autoantibodies and aid in timely recognition and treatment.

In conclusion, acute hemorrhagic dermatomyositis is an unexpected yet potentially fatal complication of dermatomyositis. Further study is needed to understand its pathogenesis, identify those at highest risk, recognize early diagnostic clues and establish effective treatments.

Akrithi Udupa, MD, is a fellow in training in the Division of Rheumatology & Immunology at Duke University Hospital, Durham, N.C.

Paul McIntosh, MD, is a chief resident in the Department of Neurology at Duke University Hospital, Durham, N.C.

Thomas J. Cummings, MD, is a pathologist at Duke University Hospital, Durham, N.C.

Lisa Criscione-Schreiber, MD, MEd, is an associate professor of medicine, rheumatology program director and vice chair for education, Department of Medicine, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, N.C.

References

- Lundberg IE. Chapter 157: Etiology and pathogenesis of inflammatory muscle disease (Myositis). In: Hochberg MC, Gravallese EM, Silman AJ, et al. Rheumatology. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 1306–1315, 2019.

- Ohashi K, Sequist LV, Arcila ME, et al. Characteristics of lung cancers harboring NRAS mutations. Clin Cancer Res. 2013 May 1;19(9):2584–2591.

- Olivier M, Hollstein M, Hainaut P. TP53 mutations in human cancers: Origins, consequences, and clinical use. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010 Jan;2(1):a001008.

- Orrell RW, Johnston HM, Gibson C, et al. Spontaneous abdominal hematoma in dermatomyositis. Muscle Nerve. 1998 Dec;21(12):1800–1803.

- Langguth DM, Wong RC, Archibald C, Hogan PG. Haemorrhagic myositis associated with prophylactic heparin use in dermatomyositis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(4):464–465.

- Higashi Y, Mera K, Kanzaki T, Kanekura T. Fatal muscle haemorrhage attributable to heparin administration in a patient with dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009 Apr;34(3):448–449.

- Yamagishi M, Tajima S, Suetake A, et al. Dermatomyositis with hemorrhagic myositis. Rheumatol Int. 2009 Sep;29(11):1363–1366.

- Miwa Y, Muramatsu M, Takahashi R, et al. Dermatomyositis complicated with hemorrhagic shock of the iliopsoas muscle on both sides and the thigh muscle. Mod Rheumatol. 2010 Aug;20(4):420–422.

- Hanawa F, Inozume T, Harada K, et al. A case of dermatomyositis accompanied by spontaneous intramuscular hemorrhage despite normal coagulability. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(11):2949–2950.

- Patel D, Kamangar N. Hemorrhagic shock from spontaneous retroperitoneal bleed in a patient with dermatomyositis [meeting abstract]. Chest. 2013 Oct;144(4):330A.

- Aylanç N, Reşorlu M, Adam G, et al. Dermatomyositis complicated case with muscular hematoma. Int J Clin Res. 2014;2(4):180–182.

- Van Gelder H, Wu KM, Gharibian N, et al. Acute hemorrhagic myositis in inflammatory myopathy and review of the literature. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2014;2014:639756.

- Chen YH, Wu PC, Ko PY, Lin YN. Retroperitoneal hematoma mimicking exacerbation of dermatomyositis. Intern Med. 2015;54(8):995–996.

- Adachi R, Muro Y, Kono M, Akiyama M. Intramuscular haemorrhage in a patient with dermatomyositis and anti-TIF1γ antibodies. Eur J Dermatol. 2018 Feb 1;28(1):116–118.

- Lee JY, Kim J. Significant muscle hemorrhage associated with low-molecular-weight heparin use in dermatomyositis: A case report. J Med Cases. 2019 Sep;10(9):280–283.

- Chandler JM, Kim YJ, Bauer JL, Wapnir IL. Dilemma in management of hemorrhagic myositis in dermatomyositis. Rheumatol Int. 2020 Feb;40(2):331–336.

- Acharya N, Dhooria A, Jha S, Sharma A. Hemorrhagic myositis: Fatal presentation of a common muscle disease. J Clin Rheumatol. 2020 Aug;26(5):e112.

- Li Fraine S, Coman D, Guignard VV, Costa J-P. Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage in dermatomyositis. Am J Med. 2021 Feb;134 (2):e137-e138.