Syphilis is a chronic sexually transmitted disease (STD) caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. The clinical manifestations of syphilis are divided into four stages: 1) the primary stage, characterized by painless mucosal or cutaneous chancre at the site of infection that resolves spontaneously; 2) the secondary stage in which a generalized maculopapular rash and condyloma lata are the most characteristic manifestations; 3) the latent stage, which represents a clinically undetectable period; and 4) the tertiary stage, which develops in untreated patients, can affect up to 15–40% of patients and manifests with cardiovascular and neurologic involvement.

Ocular syphilis, previously thought to be uncommon, has drawn renewed interest due to an increase in the number of cases. The incidence has dramatically increased in the U.S. since the early 2000s with re-emergence of syphilis among homosexual males and drug users with concurrent HIV infection.1

The challenge of ocular syphilis is that it can manifest in a number of different ways, with posterior uveitis being the most common.2 Other common manifestations include interstitial keratitis, recurrent anterior uveitis, retinal vasculitis and optic neuropathy.3 Ocular symptoms can occur as early as six weeks after transmission, and it may often be the only presenting feature of systemic syphilis. Patients usually present with complaints of blurry vision and are at risk of permanent blindness if left untreated.

Patients with large vessel vasculitis, such as giant cell arteritis (GCA), can present with a spectrum of vision changes. Sudden monocular visual loss, particularly in an older adult, from arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AAION) is a feared complication of GCA because it can lead to complete visual loss.4

Our case highlights some of the similarities between these two conditions.

Case Report

A 76-year-old man with a past medical history of coronary artery disease and hyperlipidemia presented to the ophthalmology clinic with acute blurring of vision in the right eye. He had been noticing a black spot in the center of the visual field of the eye for about four days prior to presentation. He also reported distortion of his vision, as well as an inability to read out of the right eye.

Along with the visual changes, the patient reported a sharp pain in the right temple area that had occurred around the same time. He described having right posterior and occipital scalp sensitivity intermittently for the previous year, although he said the pain in the temple was new.

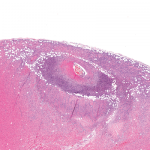

Figure 1A. Optos Fundus photo of the right eye with subtle area of retinal whitening in the macula with mild vitreous opacities inferiorly (arrowhead).

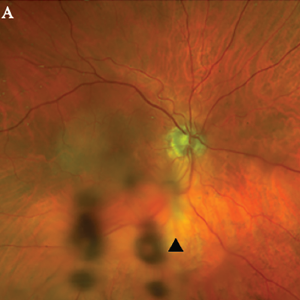

Figure 1B, Optos Fundus photo of the left eye with large placoid area of retinal whitening involving the macula (arrow), with retinal hemorrhages and vitreous opacity temporally.

He denied any eye pain, pain on eye movements, complete vision loss, new neurologic symptoms, fevers, chills, fatigue, weight loss or jaw claudication.

In the clinic, the initial fundoscopic exam appeared normal. Inflammatory markers were significantly elevated with a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 35.8 mg/L and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 130 mm/hour.

He was referred to the emergency department with a concern for giant cell arteritis.

On initial examination, patient was afebrile with stable hemodynamics. Bilateral temporal artery pulses were present and equal. There was no temporal artery nodularity or tenderness to palpation on either side.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed chronic microvascular ischemic changes, but no changes in the orbit or optic nerve. He received pulse-dose steroids with 1,000 mg of intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone daily for three days for presumed GCA, and was continued on 60 mg of oral prednisone daily. A bilateral temporal artery biopsy was performed, but was unrevealing.

The patient said his right eye vision and right temple pain improved with steroids. Given the high clinical suspicion for GCA and the improvement in his symptoms, the decision was made to continue treatment with steroids.

The patient presented to the rheumatology clinic in follow-up a few weeks later. At the time of the visit, he reported a new-onset sharp pain and blurry vision in the left eye. He denied headaches at that time and had an unrevealing physical exam. Due to his new onset of visual symptoms despite being on high-dose steroids, as well as previously negative temporal artery biopsy results, GCA was presumed to be unlikely etiology and a steroid taper was initiated by the rheumatologist.

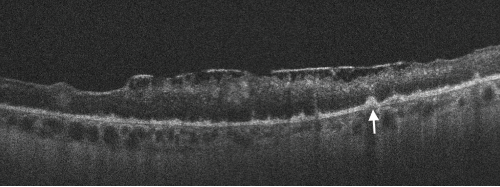

The patient was reevaluated by an ophthalmologist to address the new vision changes. Subsequent ophthalmologic exam showed bilateral placoid lesions involving the macula, characteristic for syphilitic placoid chorioretinitis (see Figures 1A&B and 2).

As a part of his broader workup, a test for Treponema pallidum was ordered. A plasma reagin (RPR) test was positive, with titers at 1:128. A fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-Abs) test was also positive.

The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist for further management. At the time of infectious disease visit, his sexual history was confirmed, and he reported a homosexual encounter with a new partner about three weeks prior to presentation. No protection was used at the time.

Further tests for infectious diseases were negative for HIV and hepatitis C. Based on his clinical presentation and high-risk sexual exposure, the diagnosis of ocular syphilis was made.

The patient had no other neurological complaints, so a decision to obtain lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis was deferred. The patient completed a 14-day course of IV penicillin. He has been closely followed up by infectious disease and ophthalmology teams. His visual symptoms improved subjectively and objectively on follow-up with ophthalmology.

Figure 2. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) of the left eye with hyper-reflective retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) nodularity (white arrow) and overlying loss of normal photo receptor architecture.

Discussion

Ocular syphilis is rare and tends to occur at any stage of the disease. However, it is commonly associated with neurosyphilis. Its incidence has been increasing in the developed countries for the past few years. This may be related in part to decreased condom use in high-risk populations following the advent of highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART).5

Because its clinical manifestations vary, ocular syphilis is a big masquerader and may be challenging to diagnose. Ocular symptoms are commonly non-specific and may lead to a delay in diagnosis and treatment. New-onset, monocular, blurry vision is usually an early manifestation; however, other non-specific systemic symptoms can mask the diagnosis.

The clinical presentation of monocular vision changes when present with relevant associated symptoms can be concerning for GCA, which can lead to permanent visual loss if untreated. Therefore establishing a definitive diagnosis is paramount.

Elevated inflammatory markers may be present in both conditions. Patients with such a presentation are often empirically treated with high-dose systemic steroids and can be subjected to a temporal artery biopsy. Because the diagnostic yield of a temporal artery biopsy is low, these patients can remain on treatment despite a negative biopsy result. A diagnosis of ocular syphilis in such cases can be missed, resulting in permanent visual impairment. A timely diagnosis of this important clinical entity can mitigate unnecessary testing and prevent complications.

Based on our experience, we recommend testing for syphilis and tuberculosis prior to initiating systemic steroid therapy. Additionally, a detailed sexual history must be obtained, and those with high-risk behaviors must also be tested for syphilis.

Iryna Nemesh, MD, is a rheumatology fellow in the Department of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, Medical College of Wisconsin Affiliated Hospitals, Milwaukee.

Saleema Kherani, MD, MPH, is an ophthalmology resident in the Department of Ophthalmology, Medical College of Wisconsin Affiliated Hospitals, Milwaukee.

Shikha Singla, MD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, Medical College of Wisconsin Affiliated Hospitals, Milwaukee.

William Wirostko, MD, is a professor of vitreoretinal surgery and ocular oncology in the Department of Ophthalmology, Medical College of Wisconsin Affiliated Hospitals, Milwaukee.

References

- Doris JP, Saha K, Jones NP, Sukthankar A. Ocular syphilis: The new epidemic. Eye (Lond). 2006 Jun;20(6):703–705.

- Majumder PD, Chen EJ, Shah J, et al. Ocular syphilis: An update. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2019;27(1):117–125.

- Kiss S, Damico FM, Young LH. Ocular manifestations and treatment of syphilis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2005;20(3):161–167.

- Biousse V, Newman NJ. Ischemic optic neuropathies. N Engl J Med. 2015 Jun 18;372(25):2428–2436.

- Fonollosa A, Giralt J, Pelegrín L, et al. Ocular syphilis-back again: Understanding recent increases in the incidence of ocular syphilitic disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009 May–Jun; 17(3):207–212.