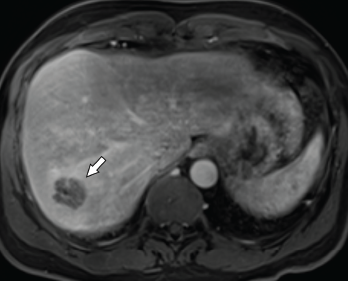

Figure 1. Axial CT of the liver, with the hepatic lobe abscess indicated by the arrow.

Abscesses are typically caused by infections, but some are, instead, sterile. Aseptic abscesses (AAs) are characterized by the same neutrophil-rich histopathology as infectious abscesses; however, they don’t improve with antibiotics. Rather, AAs require treatment with anti-inflammatory medications. Although relatively rare, this phenomenon is important for rheumatologists to recognize given its frequent association with underlying systemic inflammatory diseases.

We describe two cases of AA seen by an inpatient rheumatology consultation service within a single year.

Case 1

A 46-year-old man presented to the hospital with fever and abdominal pain. His history was notable for six hospitalizations during the previous four years for recurrent hepatic abscesses. During each of these episodes, he had negative aerobic and anaerobic cultures of abscess aspirates and blood. Additional negative microbiological testing included human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Coxiella, echinococcus and Entamoeba histolytica. Universal polymerase chain reaction testing (completed through the University of Washington Medical Center laboratory) for bacteria, fungi, mycobacterium tuberculous and nontuberculous mycobacterium was negative.

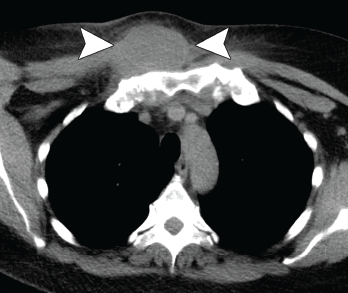

Figure 2. Axial CT showing a chest wall abscess.

His condition had temporarily improved with antibiotics during all but the last of the previous episodes. For that hospitalization, he was treated for a possible anatomic abnormality with placement of a biliary stent. He had experienced no recurrent abscess formation over the subsequent 18 months until the current hospitalization.

During the current hospitalization, the patient’s vital signs on admission were notable for a temperature of 103.5°F and sinus tachycardia of 110 beats per minute.

The initial laboratory testing demonstrated mild leukocytosis with a total white blood cell (WBC) count of 12.9×109/L (reference range [RR]: 4.0–11.0×109/L), and elevated inflammatory markers with an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 82 mm/hour (RR: 0–15 mm/hour for men younger than 50) and a C-reactive protein (CRP) of 32.6 mg/dL (RR: 0–0.6 mg/dL).

Imaging revealed four, right-lobe, hepatic abscesses measuring up to 3.0 cm in diameter (see Figure 1, above left), as well as an anorectal abscess and possible fistula of the gluteal fold.

One should have a strong suspicion for aseptic abscesses in a patient with abscesses that do not appropriately respond to antibiotic therapy.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics were initiated.

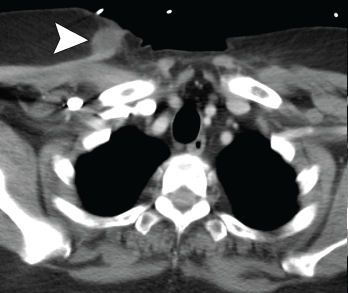

Figure 3. Axial CT showing a second chest wall abscess.

Aerobic and anaerobic cultures of abscess aspirate failed to identify an organism. Fungal and acid-fast bacillus (AFB) cultures were negative. Additional tests, including hepatitis B and C serologies, anti-Bartonella antibody, Fungitell, blastomyces antigen and cryptococcal antigen, were all negative.

The patient’s history was also notable for recurrent, oral, aphthous ulcers and pyoderma gangrenosum in the preceding year. Due to the concern for occult inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), fecal calprotectin was obtained, but was indeterminate at 89.7 mg/kg (negative: <50 mg/kg).

Colonoscopy demonstrated a possible perianal fistula and a single rectal ulcer. Biopsy of the terminal ileum was unremarkable. Rectal ulcer biopsy demonstrated non-specific reactive changes, and a biopsy of perianal tissue demonstrated acute and chronic inflammation with ulcer and abscess. X-ray and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis demonstrated sacroiliitis, despite a lack of inflammatory back pain.

Due to a lack of improvement with antimicrobials and a high suspicion for IBD, antibiotics were stopped, and he was started on 40 mg of prednisone daily. His fever and abdominal pain resolved. Adalimumab was initiated with no recurrence of abscesses to the present time.