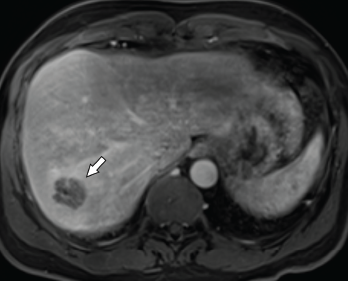

Figure 1. Axial CT of the liver, with the hepatic lobe abscess indicated by the arrow.

Abscesses are typically caused by infections, but some are, instead, sterile. Aseptic abscesses (AAs) are characterized by the same neutrophil-rich histopathology as infectious abscesses; however, they don’t improve with antibiotics. Rather, AAs require treatment with anti-inflammatory medications. Although relatively rare, this phenomenon is important for rheumatologists to recognize given its frequent association with underlying systemic inflammatory diseases.

We describe two cases of AA seen by an inpatient rheumatology consultation service within a single year.

Case 1

A 46-year-old man presented to the hospital with fever and abdominal pain. His history was notable for six hospitalizations during the previous four years for recurrent hepatic abscesses. During each of these episodes, he had negative aerobic and anaerobic cultures of abscess aspirates and blood. Additional negative microbiological testing included human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Coxiella, echinococcus and Entamoeba histolytica. Universal polymerase chain reaction testing (completed through the University of Washington Medical Center laboratory) for bacteria, fungi, mycobacterium tuberculous and nontuberculous mycobacterium was negative.

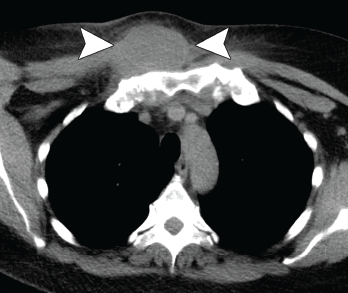

Figure 2. Axial CT showing a chest wall abscess.

His condition had temporarily improved with antibiotics during all but the last of the previous episodes. For that hospitalization, he was treated for a possible anatomic abnormality with placement of a biliary stent. He had experienced no recurrent abscess formation over the subsequent 18 months until the current hospitalization.

During the current hospitalization, the patient’s vital signs on admission were notable for a temperature of 103.5°F and sinus tachycardia of 110 beats per minute.

The initial laboratory testing demonstrated mild leukocytosis with a total white blood cell (WBC) count of 12.9×109/L (reference range [RR]: 4.0–11.0×109/L), and elevated inflammatory markers with an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 82 mm/hour (RR: 0–15 mm/hour for men younger than 50) and a C-reactive protein (CRP) of 32.6 mg/dL (RR: 0–0.6 mg/dL).

Imaging revealed four, right-lobe, hepatic abscesses measuring up to 3.0 cm in diameter (see Figure 1, above left), as well as an anorectal abscess and possible fistula of the gluteal fold.

One should have a strong suspicion for aseptic abscesses in a patient with abscesses that do not appropriately respond to antibiotic therapy.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics were initiated.

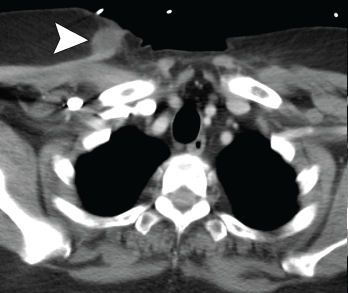

Figure 3. Axial CT showing a second chest wall abscess.

Aerobic and anaerobic cultures of abscess aspirate failed to identify an organism. Fungal and acid-fast bacillus (AFB) cultures were negative. Additional tests, including hepatitis B and C serologies, anti-Bartonella antibody, Fungitell, blastomyces antigen and cryptococcal antigen, were all negative.

The patient’s history was also notable for recurrent, oral, aphthous ulcers and pyoderma gangrenosum in the preceding year. Due to the concern for occult inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), fecal calprotectin was obtained, but was indeterminate at 89.7 mg/kg (negative: <50 mg/kg).

Colonoscopy demonstrated a possible perianal fistula and a single rectal ulcer. Biopsy of the terminal ileum was unremarkable. Rectal ulcer biopsy demonstrated non-specific reactive changes, and a biopsy of perianal tissue demonstrated acute and chronic inflammation with ulcer and abscess. X-ray and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis demonstrated sacroiliitis, despite a lack of inflammatory back pain.

Due to a lack of improvement with antimicrobials and a high suspicion for IBD, antibiotics were stopped, and he was started on 40 mg of prednisone daily. His fever and abdominal pain resolved. Adalimumab was initiated with no recurrence of abscesses to the present time.

Case 2

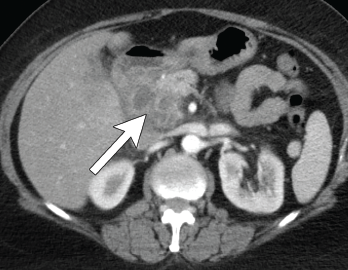

Figure 4. Axial CT showing multilocular abdominal fluid collection.

A 56-year-old woman presented to the hospital with chest and abdominal pain. Her history was notable for pustular psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis (untreated), relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (not on therapy), as well as recurrent abscesses over the preceding four years. Abscesses occurred at the chest wall (see Figures 2 & 3, opposite), axilla and pancreas.

She was treated with systemic antibiotics, although aerobic, anaerobic and AFB cultures were repeatedly negative during each of these episodes. Additional testing included negative results for anti-nuclear antibody, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, anti-myeloperoxidase antibody, anti-proteinase 3 antibody and human leukocyte antigen B27. Computerized tomography (CT) of the abdomen/pelvis demonstrated a possible duodenal-colonic fistula that was not further evaluated. Her symptoms improved with corticosteroids.

One year later she was admitted with chest and abdominal pain. She was afebrile, hypertensive up to 200/110 mmHg (RR: <120 mmHg systolic, <80 mmHg diastolic), without tachycardia or abnormal respiratory rate. Initial labs were notable for leukocytosis with a total WBC of 22.2 x 109/L (RR: 4.0–11.0 x 109/L) and elevated inflammatory markers with ESR 82 mm/h (RR: 0–30 mm/hour for women over 50) and a CRP of 10.6 mg/dL (RR: 0–0.6 mg/dL). CT scan of the chest/abdomen/pelvis demonstrated a 2.3×4 cm peri-pancreatic abscess with fat stranding and associated lymphadenopathy (see Figures 4 & 5, p. 22).

Figure 5. Coronal CT showing multilocular abdominal fluid collection.

Cultures from the abscess aspirate again failed to identify an organism, and 40 mg of prednisone daily was initiated. Despite this, she developed a new chest wall abscess over the following days. Incision and drainage were performed, with negative cultures. The following day she developed skin erythema, and pain and warmth at the incision and drainage sites. Due to concern for possible cellulitis, corticosteroids were stopped and she was started on antibiotics.

Ultimately, however, a new chest wall abscess developed, prompting re-initiation of 40 mg of prednisone daily. Her chest wall lesions improved over the following days. Due to suspicion of possible underlying IBD, a fecal calprotectin was tested but proved indeterminate at 106 mg/kg (negative: <50 mg/kg). Colonoscopy was subsequently performed and was unremarkable.

A diagnosis of synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis syndrome (SAPHO) was considered given her chest wall lesions and psoriasis, but she lacked other clinical features of osteitis, hyperostosis or acne. She was diagnosed with spondyloarthropathy-associated aseptic abscess syndrome. She was discharged on a prednisone taper and subsequently lost to follow-up.

Discussion

Aseptic abscesses were first described in 1995 in the case of a 25-year-old man who developed multiple abscesses several years prior to an eventual diagnosis of Crohn’s disease.1 In 2007, the most complete description of this new entity was published with the inclusion of 30 cases from a French registry and 19 cases compiled from a literature review.2 The researchers defined AA by the radiographic appearance of an abscess, negative microbial diagnostic studies, lack of response to antibiotic therapy and rapid response to corticosteroids (see Table 1).2

Table 1: The 5 Features of Aseptic Abscesses

| 1. Presence of abscess on radiologic examination |

|---|

| 2. Histopathology with neutrophilic features |

| 3. Negative blood cultures and infectious evaluation |

| 4. Failure of antibiotic therapy (defined as >2 weeks of therapy or >3 months if concern for tuberculosis) |

| 5. Improvement with steroids |

Within this series, AA typically occurred in young adults and were in the spleen in the vast majority of cases (93%). Other involved areas included abdominal lymph nodes (48%), the liver (40%), lung (17%), pancreas (7%) and brain (2%). Most patients had fever (90%), as well as abdominal pain (67%) and weight loss (50%). Laboratory studies were non-specific, demonstrating leukocytosis in most patients (70%).2

In the cases in which an underlying condition could be identified, the condition was typically in the autoinflammatory spectrum of diseases (see Table 2, above). The majority (70%) of patients were ultimately diagnosed with IBD. Importantly, one-third of patients were diagnosed with IBD prior to the presentation of aseptic abscesses, one-third concurrently with IBD and one-third with a later diagnosis of IBD.2

Neutrophilic dermatoses, a heterogeneous group of inflammatory skin disorders characterized by a sterile dense infiltration of neutrophils in affected tissues (e.g., pyoderma gangrenosum), may exist on a continuum with AA.3 Supporting this observation, 20% of patients from the initial cohort were diagnosed with identifiable neutrophilic dermatoses.2,4

Further, neutrophilic dermatoses are well-described clinical manifestations of the autoinflammatory diseases associated with AA.3 Despite this clear association, it is important to note that the histopathologic features of AA and neutrophilic dermatoses are different—in AA, the abscesses can be surrounded by granulomatous reaction, which is atypical in neutrophilic dermatoses.2

One should have a strong suspicion for AA in a patient with abscesses that do not appropriately respond to antibiotic therapy, particularly in the setting of an autoinflammatory syndrome and/or neutrophilic dermatosis. In a patient with a suspected AA, one should thoroughly evaluate for an infectious process.

All patients should have blood cultures, as well as appropriate cultures of the abscess (including AFB and fungal). Consideration should also be made for testing for HIV or Tropheryma whipplei in patients with lymphadenopathy, arthralgias, gastrointestinal symptoms or weight loss.4 Given the high prevalence of associated (often occult) IBD, evaluation for IBD should be completed in all patients.

Treatment guidelines for AA do not exist, but first-line treatment typically consists of high-dose glucocorticoids (0.5–1 mg/kg). Given the high rate of recurrence, steroid-sparing agents are frequently trialed. A 2019 literature review detailed the use of multiple agents, including disease-modifying anti-

rheumatic drugs (e.g., most typically azathioprine, but also methotrexate, cyclosporine and mycophenolate), colchicine and biologic therapy (e.g., typically tumor necrosis factor [TNF] inhibitors, but also agents that block interleukin [IL] 1 and IL-6). Of these agents, TNF inhibitors had high rates of complete clinical responses and would generally be considered the initial treatment of choice.5

Table 2: Systemic Diseases Seen in Association with Aseptic Abscesses

| Systemic Disease | Key Clinical Features |

|---|---|

| Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) | • Characterized by inflammatory changes of the GI tract |

| Synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis (SAPHO) | • Skin lesions include palmoplantar psoriasis and nodular acne • Neutrophilic dermatoses can be seen as part of the disease process • Osteitis most commonly involves the anterior chest wall, sacroiliac joint or spine |

| Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO)/chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis | • Typical onset in childhood with unifocal or multifocal osteomyelitis involvement of bones, including the metaphysis of the long bones of the lower extremities (most common), as well as the pelvis, vertebrae, clavicle, long bone of upper extremities and mandible |

| Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic fever (TRAPs) | • Periodic fever syndrome with typical onset in childhood, characterized by episodes of fevers lasting five days to two weeks and occurring every five to six weeks. |

| Pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum and acne (PAPA) | • Autosomal dominant disorder typically with childhood onset, characterized by destructive arthritis, nodular acne and absence of fevers |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne and hidradenitis suppurativa (PASH) | • Triad of multiple neutrophilic dermatoses including pyoderma gangrenosum, acne and hidradenitis suppurativa |

| Pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, suppurative hidradenitis (PAPASH) | • Characterized by arthritis and multiple skin lesions |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | • Characterized by abnormal blood cell maturation of a cell line leading to cytopenia(s) |

| Behçet’s disease | • A variable vessel size vasculitis • The disease is characterized by recurrent oral and genital ulcers • This multisystem disorder can include eye, gastrointestinal, neurologic and vascular disease |

| Relapsing polychondritis | • Chronic inflammation of cartilaginous structures • Typically involves the ears, nose, eye, respiratory tract and joints |

In Sum

Here, we describe two patients seen in our inpatient rheumatology consultation service who were ultimately diagnosed with aseptic abscesses. As can be appreciated by these cases, substantial delays in diagnosis of this disease entity can occur. Increased awareness of this likely under-recognized disease would result in earlier recognition and treatment, potentially preventing significant morbidity.

Katherine Chakrabarti, MD, is a recent graduate of the rheumatology fellowship program and is a current clinical assistant professor in the Division of Rheumatology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Andrew Vreede, MD, is a clinical assistant professor in the Division of Rheumatology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and also serves in the Rheumatology Section of Ann Arbor Veterans Administration Healthcare System.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Michelle Sakala, MD, and Mahmoud Al-Hawary, MD, for their interpretation and preparation of imaging, as well as Rory Marks, MD, for reviewing the manuscript.

References

- André M, Aumaitre O, Marcheix JC, Piette JC. Aseptic systemic abscesses preceding diagnosis of Crohn’s disease by three years. Dig Dis Sci. 1995 Mar;40(3):525–527.

- André MFJ, Piette JC, Kémény JL, et al. Aseptic abscesses: A study of 30 patients with or without inflammatory bowel disease and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007 May;86(3):145–161.

- Vignon-Pennamen MD. The extracutaneous involvement in neutrophilic dermatoses. Clin Dermatol. May–Jun 2000;18(3):339–347.

- André M, Aumaître O. Aseptic abscesses syndrome. Rev Med Interne. 2011 Nov; 32(11):678–688.

- Elessa D, Thietart S, Corpechot C, et al. TNF-α antagonist infliximab for aseptic abscess syndrome. Presse Med. 2019 Dec;48(12):1579–1580.