Presentation

A 26-year-old man with a history of acne vulgaris and hidradenitis suppurativa presented to our rheumatology clinic with persistent back pain and stiffness of three years’ duration. He described bilateral low back pain that was worse when he arose in the morning and at night when he was trying to sleep.

In a similar pattern to his back pain, he described right shoulder and neck pain. He described neck stiffness preventing him from being able to look over his shoulder when driving. He worked as a cashier and did not notice any worsening pain during his shifts. On his days off, when he was less active, he noticed worsening symptoms.

Physical therapy over the previous few months had not improved his pain or stiffness. Exercise, 800 mg of ibuprofen three times daily and heating pads provided only minimal relief. He did not notice any swollen joints, and a review of systems was otherwise negative. There was no family history of arthritis.

The patient was followed by a dermatologist for his severe acne, which involved his face, scalp, axilla and groin. He had been on isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoic acid) intermittently for the previous four years. His therapy was limited by generalized myalgias. The dose of isotretinoin varied from 20 mg to 60 mg daily, with a two-year pause from therapy due to myalgias and, because the patient was attempting to lose weight, the need to take the medication with a high-fat meal. Two years prior to presentation he completed a four-month course with a cumulative total dose of 8,880 mg. Most recently, his cumulative dose of isotretinoin reached a value of 19,760 mg (170 mg/kg) and was, therefore, discontinued.

The physical exam was remarkable for a body mass index of 35, in addition to several skin and musculoskeletal findings. He had atrophic scarring of his face without papules, hypopigmented scaling lesions on his scalp, hyperpigmentation on the back of his neck and erythematous papules and scarring in both axillae. He had no nail abnormalities and no appreciable synovitis of his fingers, wrists, elbows, knees, ankles or toes. He exhibited reduced right shoulder external rotation due to pain. Bilateral hips exhibited reduced symmetrical external rotation; no back tenderness was elicited with active or passive hip movements. He did not have entheseal tenderness in his triceps, pectoris, quadriceps, patellar or Achilles tendons or plantar fasciae.

His axial mobility was markedly abnormal. The occiput to wall was approximately 8 cm (0 is normal). Tragus to wall distance measured 24 cm (less than 15 cm is normal). He had 0 cm excursion on the modified Schoeber test (greater than 5 is normal). Chest expansion only reached 3.5 cm (normal for his age and sex is 6.2–9.0 cm). Cervical spine flexion was preserved. He had decreased lateral flexion of cervical spine and slightly reduced cervical rotation. Lateral lumbar spine flexion reached 10 cm excursion on the left and 5 cm excursion on the right (greater than 10 cm is normal). Lumbar flexion was limited to 30º and he was unable to touch his toes. He did not have any sacroiliac joint tenderness.

The laboratory work-up revealed a normal complete blood count, liver function tests and hemoglobin A1C. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was mildly elevated to 29 mm/HR, with a previous available level of 18. His C-reactive protein (CRP) was 1.9 mg/L. He was negative for HLA-B27.

Imaging

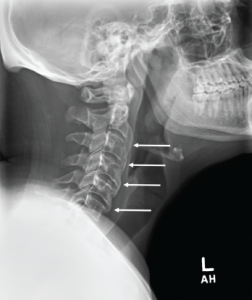

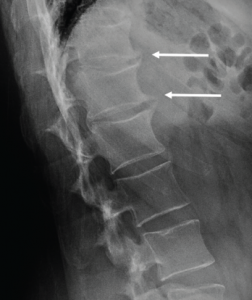

A cervical spine radiograph (Image 1) was remarkable for the presence of flowing ossifications bridging the anterior margins of the C2-C6 vertebra, with a relative lack of disc space narrowing. A radiograph of the lumbar spine (Image 2) demonstrated mild intervertebral disc space narrowing with marginal osteophytes and end plate sclerosis at T12–L1 and L1–L2.

Image 1: Cervical spine radiograph, lateral view, demonstrating flowing anterior ossifications (white arrows) bridging four consecutive vertebrae (C2–C3 through C5–C6), but with relative preservation of the disc space.

Image 2: Lumbar spine radiograph, lateral view, demonstrating anterior endplate osteophytes at the levels of T12–L1 and L1–L2 (white arrows).

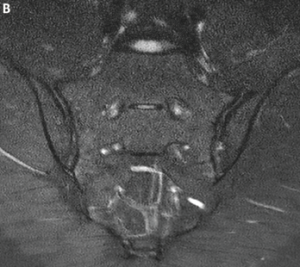

An MRI of the pelvis without gadolinium (Images 3a and 3b) demonstrated bridging anterior ossifications along the left sacral iliac joint with only mild chondral loss and reactive bone marrow edema pattern. There were no bone erosions.

Image 3a: MRI of the sacroiliac joints. Panel A shows a proton density oblique coronal image demonstrating bridging ossifications along the anterior aspect of the left sacroiliac joint (black arrow) with only minimal chondral thinning within the joint itself. Panel B shows a fat-suppressed T2-weighted image of the same region, demonstrating no areas of synovitis, subchondral bone marrow edema or erosion to suggest an inflammatory arthritis.

Image 3b

Diagnosis

The differential for this patient included ankylosing spondylitis (AS); synovitis,

acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis and osteitis (SAPHO); diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) and retinoid hyperostosis (RH). DISH is clinically synonymous to RH except that in RH an etiology has been established.

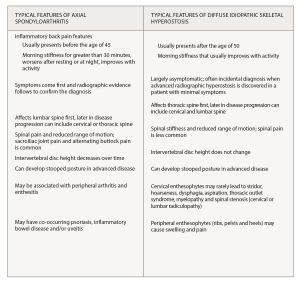

Because of the patient’s extensive isotretinoin history and the extensive anterior ossifications of the cervical spine, he was thought to have RH from isotretinoin. Clues on history suggesting RH included severe acne requiring prolonged intensive medical treatment. His history of back pain had some inflammatory features, but notably his pain failed to improve with activity or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which are key features of inflammatory back pain (Box 1).

The patient’s insulin resistance, suggested by acanthosis nigricans on the back of his neck, also points toward hyperostosis. Insulin resistance has been documented as a risk factor for DISH and, therefore, likely a risk factor for RH as well.1 Lastly, while patients with SAPHO exhibit pustular acne and hyperostosis, these patients typically have chest wall involvement, whereas this patient has predominantly cervical spine involvement. SAPHO is a diagnosis of exclusion, whereas in this patient, isotretinoin was considered the likely culprit for his symptoms.

Discussion

DISH is a non-inflammatory disorder of bone in which ossification of ligaments and entheses occurs. DISH may be asymptomatic or a contributor to axial and peripheral joint pain and stiffness. Risk factors for DISH include male sex, advanced age and hyperinsulinemia. DISH most commonly affects the thoracic spine, where flowing ossifications may be visible along the anterolateral aspect of the vertebral bodies, typically on the right side. Other common sites for DISH include the cervical and lumbar spine, as well as entheses in the pelvis, knees, heels and shoulders.

Most patients with DISH are discovered to have the syndrome incidentally when found on imaging.1 It can be mistaken for AS because both problems often present with back stiffness and back pain.4 Several features distinguish DISH from inflammatory spondyloarthritis. First of all, DISH most commonly presents in men 50 years or older, but AS usually presents in those younger than age 45. Patients with DISH may not complain of back pain but rather stiffness that improves with activity. However, some patients progress to having back pain as well.

Back symptoms usually start in the thoracic spine in DISH, whereas patients with AS usually develop lumbar back pain first. Patients with AS may also develop intermittent buttock pain. As DISH progresses, it can include the cervical and lumbar spine. Cervical spine enthesophytes in DISH can lead to several extra-axial symptoms, such as stridor, hoarseness, dysphagia, thoracic outlet syndrome, myelopathy and spinal stenosis.1 These complications are rare.

Both diseases, when advanced, can lead to a stooped posture, decreased range of motion, stiffness and pain throughout the cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine. To confirm the diagnosis, the most reliable way to distinguish spondyloarthritis from DISH is by incorporating radiographic and laboratory findings with the clinical presentation. Interestingly, some patients with DISH have been found to have elevated serum levels of vitamin A, whereas patients with AS have been found to have paradoxically lower levels.5

DISH is a non-inflammatory disorder of bone in which ossification of ligaments & entheses occurs.

Vitamin A, Bone Metabolism & the Development of Hyperostosis

Vitamin A is involved in bone metabolism through multiple routes. Indirectly, it is a factor in stem cell growth and differentiation. It is a component in bone formation and resorption, though the mechanism of bone formation is unclear. Regarding bone resorption, vitamin A has been found to stimulate osteoclasts to resorb bone, and at the same time inhibit the formation of osteoclasts.6

When retinoids are ingested, they attach to retinoid binding protein for uptake into peripheral cells. Vitamin A is primarily stored in the liver, but chylomicrons take one-quarter to one-third of dietary retinoids and deposit them outside the liver, with bone the next most common site for metabolism.6 Once inside cells, retinol is converted to all-trans retinol via oxidation. All-trans retinal is then oxidized to all-trans retinoic acid, which is the active compound required to properly bind to the multitude of proteins and receptors with which it interacts.

(click for larger image) Box 1*

* Information from Mader et al,1 Cuesta-Vargas et al.2 and Taurog et al.3

Isotretinoin, a vitamin A derivative, is commonly used for the treatment of severe recalcitrant acne vulgaris. Five biologically active forms of this compound are known, but only tretinoin and 4-oxo-tretinoin are recognized to bind to the retinoic acid receptor gamma (RAR-γ), leading to downstream improvement in acne. Although it is not directly antimicrobial, isotretinoin works to make the skin less habitable for Propionibacterium acnes and therefore reduces inflammation. It decreases the size of pilosebaceous ducts by targeting the smooth endoplasmic reticulum. This, in turn, decreases the amount of sebum produced.7

Prolonged courses and high doses of isotretinoin and other vitamin A derivatives have been linked to development of hyperostosis.8-10 The frequency of hyperostosis is unknown, but the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has observed “a high prevalence” among patients with disorders of keratinization when mean doses reached 2.24 mg/kg/day.11 When treating acne vulgaris, isotretinoin doses of 120 to 150 mg/kg are typically used as part of a 20-week course. However, in some cases, high cumulative doses (over 220 mg/kg) are used to reduce the risk of acne relapse.12

An excess of vitamin A has been associated with a range of bone pathologies. Case studies of individuals taking high doses of synthetic retinoids have demonstrated premature epiphyseal closure, increased cortical bone resorption and periosteal bone formation. These individuals endorsed skeletal and joint pain and exhibited hyperostosis in the long bones, metatarsals and metacarpals. Decreased bone mass, osteoporosis and fractures have been documented.6

It is hypothesized that isotretinoin contributes to hyperostosis through acceleration of skeletal maturation. Animal models have shown exposure to high levels of vitamin A lead to faster cartilage and periosteal growth and more bone remodeling.8 Although the mechanism of hyperostosis is unclear, two hypotheses could explain this phenomenon. One is that osteoblastic cells are stimulated by hypervitaminosis A, leading to more bone production.9 Another is that hypervitaminosis A leads to osteopenia, which then stimulates osteoblastic cells to produce more bone.9

Although it is uncertain whether vitamin A and its derivatives are involved in the development of DISH, some studies have found patients with DISH to have higher levels of vitamin A than the general population.1 Therefore, it is possible that DISH is a metabolic syndrome and that vitamin A plays a larger role in the manifestation of DISH than previously thought. Further studies are needed to understand the impact of high-dose retinoids on bone health and functional status.

Conclusion

This clinical encounter is an opportunity to differentiate spondyloarthritis from skeletal hyperostosis. Our experience highlights retinoid hyperostosis, a condition nearly identical to diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis, as a rare cause of axial pain. Although uncommon, this diagnosis is important to make, because if caught early, cessation of isotretinoin can be recommended, and musculoskeletal symptoms can potentially be reversible.10

Rachael Stovall, MD, is a resident in the Department of Internal Medicine at Boston Medical Center. She completed her medical degree at the University of Washington.

Rachael Stovall, MD, is a resident in the Department of Internal Medicine at Boston Medical Center. She completed her medical degree at the University of Washington.

Akira M. Murakami, MD, is an assistant professor of radiology at Boston University School of Medicine and the section head of musculoskeletal imaging at Boston Medical Center.

Akira M. Murakami, MD, is an assistant professor of radiology at Boston University School of Medicine and the section head of musculoskeletal imaging at Boston Medical Center.

Maureen Dubreuil, MD, MSc, is an assistant professor of medicine in the sections of clinical epidemiology and rheumatology at Boston University Medical Center.

Maureen Dubreuil, MD, MSc, is an assistant professor of medicine in the sections of clinical epidemiology and rheumatology at Boston University Medical Center.

References

- Mader R, Verlaan JJ, Buskila D. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis: Clinical features and pathogenic mechanisms. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013 Dec;9(12):741–750.

- Cuesta-Vargas A, Farasyn A, Gabel CP, Luciano JV. The mechanical and inflammatory low back pain (MIL) index: development and validation. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014 Jan 9;15:12.

- Taurog JD, Chhabra A, Colbert RA. Ankylosing spondylitis and axial spondyloarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2016 Jun 30;374(26):2563–2574.

- Olivieri I, D’Angelo S, Palazzi C, et al. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis: Differentiation from ankylosing spondylitis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2009 Oct;11(5):321–328.

- O’Shea FD, Tsui FW, Chiu B, et al. Retinol (vitamin A) and retinol-binding protein levels are decreased in ankylosing spondylitis: clinical and genetic analysis. J Rheumatol. 2007 Dec;34(12):2457–2459.

- Conaway HH, Henning P, Lerner UH. Vitamin A metabolism, action, and role in skeletal homeostasis. Endocr Rev. 2013 Dec;34(6):766–797.

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009 May;1(3):162–169.

- Pennes DR, Ellis CN, Madison KC, et al. Early skeletal hyperostoses secondary to 13-cis-retinoic acid. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984 May;142(5):979–983.

- Petscavage JM, Grauke LJ, Richardson ML. Retinoic acid arthropathy: An unusual cause of elbow pain. Radiol Case Rep. 2015 Nov 6;5(3):427.

- Pittsley RA, Yoder FW. Retinoid hyperostosis. Skeletal toxicity associated with long-term administration of 13-cis-retinoic acid for refractory ichthyosis. N Engl J Med. 1983 Apr 28;308(17):1012–1014.

- Accutane (isotretinoin capsules). 2010 Jan; Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- Blasiak RC, Stamey CR, Burkhart CN, Lugo-somolinos A, Morrell DS. High-dose isotretinoin treatment and the rate of retrial, relapse, and adverse effects in patients with acne vulgaris. JAMA Dermatol. 2013 Dec;149(12):1392–1398.