The following report outlines a case of newly diagnosed adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD) complicated by macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) in a previously healthy and active 32-year-old man who had emigrated from Africa to the U.S.

The following report outlines a case of newly diagnosed adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD) complicated by macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) in a previously healthy and active 32-year-old man who had emigrated from Africa to the U.S.

Case

A man with no prior medical history presented with acute-onset polyarthritis, fevers and fatigue that began one month previously. He had been seen in the emergency department several times and had multiple visits to his primary care doctor, who also noted elevated inflammatory markers.

In addition to the arthritis, he had developed a transient, diffuse rash and gross hematuria one week earlier. A review of systems also revealed sore throat, cough, pleuritic chest pain, muscle weakness, and an inability to walk. His symptoms were not relieved by ibuprofen.

On physical exam, the patient appeared ill, in mild distress and was sitting in a wheelchair. The patient had active synovitis, with notable red, hot, swollen joints in his fingers, knees, ankles and wrists. He had difficulty making a fist with both hands. The patient was prescribed 60 mg of prednisone daily and instructed to follow up in one week to review the results of his laboratory tests.

Laboratory results: elevated AST 170 U/L (normal range: 17–59 U/L), ALT 135 U/L (normal range: 0–57 U/L), albumin 3.2 g/dL (normal range: 3.5–5.0 g/dL) white blood cell count 23.2K/mcL (normal range: 4.5–11K/mcL) with 96% polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 37 mm/hr (normal range: 0–15 mm/hr), C-reactive protein (CRP) 328.2 mg/L (normal range <10 mg/L). Most notably, ferritin was significantly elevated at 20,853.3 ng/mL (normal range: 3.8–10.6 ng/mL).

Due to these markedly abnormal lab results and lack of improvement with high-dose glucocorticoids, the patient was directly admitted to the hospital for further evaluation. Specialists in infectious disease, rheumatology, oncology and orthopedic surgery followed this patient during his hospitalization.

Extensive infectious disease testing was performed, ruling out SARS-CoV-2, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, parvovirus B-19, influenza, malaria, histoplasmosis and tuberculosis. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Uric acid levels, rheumatoid factor and antistreptolysin O antibodies were within normal limits. Chest X-ray, computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine revealed no acute pathology, signs of infection or masses. Transthoracic echocardiogram was negative for valvular vegetation.

On hospital day 3, synovial fluid analysis of the left knee revealed some calcium pyrophosphate crystals.

Despite acetaminophen use during his seven-day hospitalization, the patient’s temperature waxed and waned, with a documented maximum temperature of 102.5ºF. He experienced continued fevers despite intravenous antibiotic treatment for the first 72 hours of hospitalization, thus his regimen was broadened to include daptomycin, meropenem and doxycycline.

The patient continued to have significant elevation of his ferritin levels, joint pain and fevers, suspicious for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH)/macrophage activation syndrome (MAS). On hospital day 4, 1 g of intravenous methylprednisolone daily for three days was initiated, which led to reduced joint pain and decreased fevers.

To further evaluate for HLH, a bone marrow biopsy was performed on hospital day 5, demonstrating hemophagocytosis, consistent with HLH/MAS. The bone marrow biopsy also revealed hypercellular bone marrow, trilineage hematopoiesis without abnormal B cells or blasts on flow cytometry, which reduced the likelihood of a bone marrow malignancy.

The soluble IL-2 alpha receptor level was elevated at 2,202 U/mL (normal: 858 U/mL).

Prior to discharge, the patient was transitioned from intravenous methylprednisolone to 60 mg of oral prednisone daily, with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for prophylaxis against Pneumocystis.

While on a slow steroid taper, the patient developed steroid-induced psychosis, thus was tapered off steroids over the following two weeks. During this time, he continued to have joint pain; thus, 100 mg of subcutaneous anakinra daily was prescribed.

For six months following initiation of anakinra, the patient complained of diffuse pruritus and dry cough, which he attributed to the anakinra. The anakinra was discontinued, and the patient started canakinumab. He continued to have knee and shoulder pain; thus, 25 mg of subcutaneous methotrexate weekly was added, and his joint pain resolved.

One year following the onset of AOSD, the patient began to complain of dry eyes and dry mouth and was found to be anti-SSA antibody positive. Hydroxychloroquine was added to his regimen.

The patient is now stable and asymptomatic on canakinumab, methotrexate and hydroxychloroquine. He is able to live an active life with his wife and three young children.

Discussion

Adult-onset Still’s disease is a condition defined by a systemic inflammatory response whose pathogenesis remains unclear. The annual incidence of AOSD is 0.16 per 100,000 people.11 However, delays in diagnosis make it likely that the incidence is higher.1 There is apparently a bimodal distribution in the age of onset, with peaks between 15–25 years of age and 36–46 years of age. There also appears to be a higher occurrence among women, for unknown reasons.11,2

The classic description of symptoms includes arthritis, fever, evanescent rash and elevated ferritin levels. However, patients may also present with other clinical features, including sore throat, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy and serositis.6

The disease course generally follows one of three patterns: 1) a singular, self-limited episode (i.e., monocyclic); 2) a pattern of continued flares with periods of remission (i.e., polycyclic); and 3) continued signs and symptoms with no periods of remission (i.e., chronic).3 At almost two years from initial diagnosis, our patient’s disease remains in remission; thus, he follows the monocyclic pattern.

There are no specific tests that confirm a diagnosis of AOSD; however, laboratory tests commonly show non-specific signs of generalized inflammation, including anemia, thrombocytosis, elevated inflammatory markers and significantly elevated ferritin. Of note, ferritin is usually markedly elevated and found to be much higher than in other autoimmune, infectious, inflammatory or neoplastic diseases. Higher levels of ferritin may also be an indicator of MAS.5

Click to enlarge.

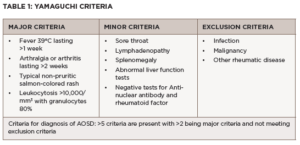

Although AOSD is largely a clinical diagnosis, clinicians can use the Yamaguchi criteria and Fautrel criteria to help classify it. As seen in Table 1, the Yamaguchi criteria require that five or more criteria be met, with at least two major criteria, and infection, malignancies and other rheumatic diseases ruled out.13 The Yamaguchi criteria has a sensitivity of 96.2% and a specificity of 92.1% in diagnosing AOSD.13

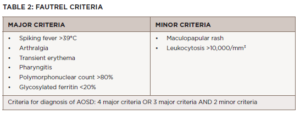

As seen in Table 2, the Fautrel criteria require at least four or more major criteria or three major criteria with two minor criteria be met. They have a sensitivity of 80.6% and specificity of 98.5%.4

Our patient’s disease characteristics fit both the Fautrel criteria and the Yamaguchi criteria because he had fever (>39ºC), leukocytosis with 96%, polymorphonuclear neutrophils, polyarthralgia/arthritis, abnormal liver function tests, pharyngitis and rash. In addition, his infectious and hematologic evaluations were negative, ruling out other causes of his presentation.

Click to enlarge.

The treatment aim for AOSD is to control inflammation and prevent end-organ damage, which can be assessed clinically and through serial measurement of inflammatory markers. The treatment initiated depends on disease severity. Patients are classified as having mild to moderate disease when symptoms are low grade, including mild fever, rash and arthralgias or arthritis. These patients may be treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). However, NSAIDs alone fail to control symptoms in 80% of AOSD patients.9 If symptoms fail to improve after a two week trial of NSAIDs, glucocorticoids are recommended for management in mild cases.9

Patients with moderate to severe disease, as in the case of our patient, typically have signs of systemic illness, including debilitating polyarthritis, persistently elevated fever despite antipyretics, and serositis. In these cases, anakinra, an interleukin 1 receptor antagonist is recommended. Studies have shown that, in AOSD patients, anakinra was more likely to induce remission than DMARDs alone, and patients on anakinra were able to decrease or eliminate glucocorticoid use.12,7 Alternative medications for patients who are unable to tolerate anakinra include the other IL-1 inhibitors canakinumab and rilonacept, as well as the IL-6 inhibitor tocilizumab.14 Of note, only canakinumab is approved by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration for the treatment of AOSD.10

Numerous complications are associated with AOSD. Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), found in up to 15% of AOSD patients, is one of the most severe complications, and the complication with the highest mortality rate.6 The mechanisms of MAS development in AOSD is unclear, but involves cytokine-induced hyperproliferation of activated CD8+ T lymphocytes and macrophages in the reticuloendothelial system.8 MAS is characterized by cytokine storm, hemophagocytosis and multi-system organ damage.2

Studies have shown that patients with AOSD complicated by MAS have a mortality rate of up to 52.9%, which is significantly higher than the mortality rate of AOSD alone, which is 9.5%.2 There are a few proposed scores for diagnosis of MAS, including the 2004-HLH criteria or H-Score, but the applicability of these tools in the context of AOSD remains unclear.

Because the diagnosis of AOSD with MAS is difficult, and the number of patients relatively low, little published literature on this topic exists. Treatment of MAS continues to evolve, with greater use of immunomodulators to help control the inflammation. Currently, high-dose intravenous glucocorticoids, which were administered to our patient and resulted in clinical improvement, remain a cornerstone of treatment.5

Even less is known about AOSD in people of African descent, with fewer than 10 cases discussed in the literature. Despite this small number of published reports, it is possible the condition is underdiagnosed. After all, there is a huge shortage of trained rheumatologists practicing within the continent of Africa. Additionally, classic textbook descriptions of AOSD describe a salmon-colored rash and in individuals with darker skin, this description may be misleading. Regardless, it is important to consider AOSD in patients of African descent who have a fever of unknown origin and significant hyperferritinemia.

Cristina Romaniello, DO, is an internal medicine resident at Riverside Methodist Hospital in Columbus, Ohio. She graduated from West Virginia School of Osteopathic Medicine in 2020. She will pursue a career as a hospitalist following her residency.

Cristina Romaniello, DO, is an internal medicine resident at Riverside Methodist Hospital in Columbus, Ohio. She graduated from West Virginia School of Osteopathic Medicine in 2020. She will pursue a career as a hospitalist following her residency.

Caitlin Kesari, MD, is a board-certified rheumatologist practicing in Columbus, Ohio. She completed her rheumatology fellowship at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center and Cincinnati VA.

Caitlin Kesari, MD, is a board-certified rheumatologist practicing in Columbus, Ohio. She completed her rheumatology fellowship at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center and Cincinnati VA.

References

- Akintayo RO, Adelowo O. Adult-onset Still’s disease in a Nigerian woman. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Jul 6;2015:bcr2015210789.

- Bae CB, Jung JY, Kim HA, et al. Reactive hemophagocytic syndrome in adult-onset Still disease: Clinical features, predictive factors, and prognosis in 21 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015 Jan;94(4):e451.

- Fautrel B. Adult-onset Still disease. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008 Oct;22(5):773–792.

- Fautrel B, Zing E, Golmard JL, et al. Proposal for a new set of classification criteria for adult-onset Still disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 2002 May;81(3):194–200.

- Gao Q, Yuan Y, Wang Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of macrophage activation syndrome in adult-onset Still’s disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2021 Sep–Oct;39 Suppl 132(5):59–66.

- Giacomelli R, Ruscitti P, Shoenfeld Y. A comprehensive review on adult onset Still’s disease. J Autoimmun. 2018 Sep;93:24–36.

- Giampietro C, Ridene M, Lequerre T, et al. Anakinra in adult-onset Still’s disease: long-term treatment in patients resistant to conventional therapy. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013 May;65(5):822–826.

- Gopalarathinam R, Orlowsky E, Kesavalu R, et al. Adult onset Still’s disease: A review on diagnostic workup and treatment options. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2016;2016:6502373.

- Franchini S, Dagna L, Salvo F, et al. Efficacy of traditional and biologic agents in different clinical phenotypes of adult-onset Still’s disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Aug;62(8):2530–2535.

- Kedor C, Listing J, Zernicke J, et al. Canakinumab for treatment of adult-onset Still’s disease to achieve reduction of arthritic manifestation (CONSIDER): phase II, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre, investigator-initiated trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 Aug;79(8):1090–1097.

- Magadur-Joly G, Billaud E, Barrier JH, et al. Epidemiology of adult Still’s disease: estimate of the incidence by a retrospective study in west France. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995 Jul;54(7):587–590.

- Nordström D, Knight A, Luukkainen R, et al. Beneficial effect of interleukin 1 inhibition with anakinra in adult-onset Still’s disease. An open, randomized, multicenter study. J Rheumatol. 2012 Oct;39(10):2008–2011.

- Yamaguchi M, Ohta A, Tsunematsu T, et al. Preliminary criteria for classification of adult Still’s disease. J Rheumatol. 1992 Mar; 19(3):424–430.

- Efthimiou P, Kontzias A, Hur P, et al. Adult-onset Still’s disease in focus: Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and unmet needs in the era of targeted therapies. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2021 Aug;51(4):858–874.

Editor’s note: The African continent is full of diversity in every aspect. Although we were unable to ascertain precisely which country or region the patient had immigrated from, the key learning point remains: Immune dysfunction is often overlooked in those living in Africa and among African diaspora communities. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for these conditions.