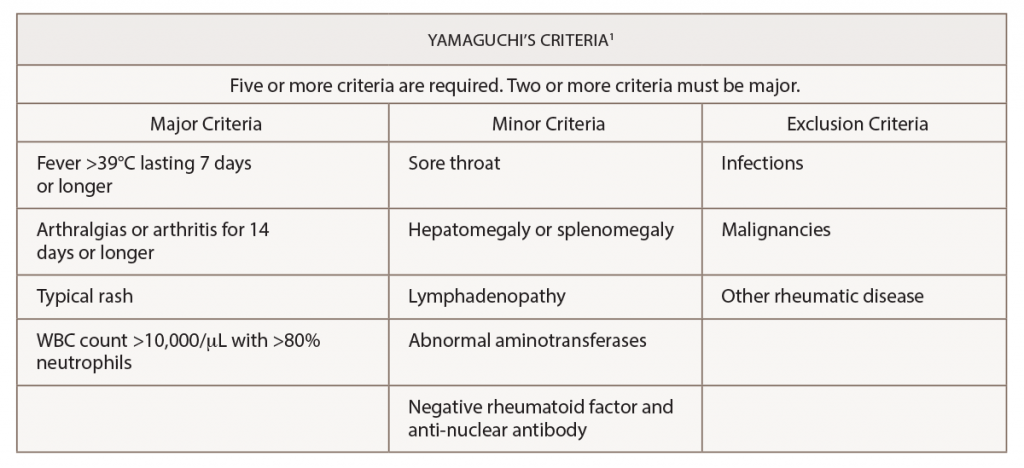

(click for larger image) Table 1: Yamaguchi’s Criteria for the Diagnosis of Adult-Onset Still’s Disease

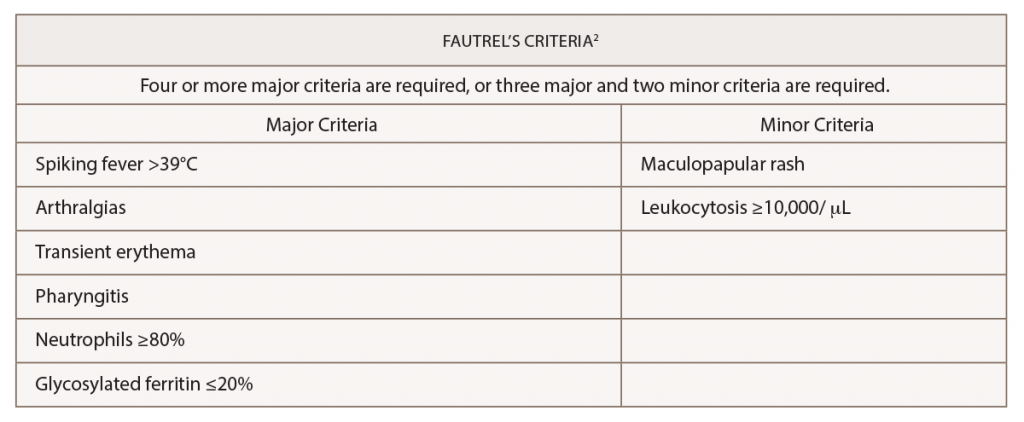

(click for larger image) Table 2: Fautrel’s Criteria for the Diagnosis of Adult-Onset Still’s Disease

The patient was started on 40 mg of methylprednisolone intravenously every eight hours.

Interventional radiology was consulted for biopsy of the retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, but the biopsy proved to be technically difficult. On the advice of a hematologist/oncologist, an outpatient positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan was arranged for further evaluation. During his hospital course, he developed bilateral deep venous thromboses, and he was started on 10 mg of apixaban twice daily for seven days and was then transitioned to 5 mg twice daily. His response to intravenous glucocorticoids was substantial, improving his synovitis, range of motion and pain. He was transitioned to 10 mg of oral prednisone daily and was discharged home.

Approximately two weeks after discharge, he returned to the hospital following a syncopal event. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of his brain demonstrated multiple patchy areas of acute ischemia in the cerebellum consistent with an acute stroke. He reported compliance with the apixaban after hospital discharge; however, he had stopped taking the steroids, and the symmetric inflammatory arthritis had recurred.

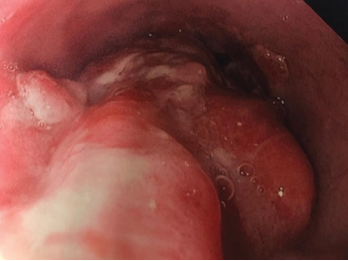

Due to his persistent abdominal lymphadenopathy, bilateral deep venous thromboses, a guaiac-positive stool test and the recent stroke, which was thought to be thromboembolic despite anticoagulation, we were concerned about the possibility of a paraneoplastic hypercoagulable state. A gastroenterologist was consulted for endoscopic evaluation to aid the investigation into the abdominal lymphadenopathy (see Figure 2, above). Evaluation revealed a large, 4 cm polypoid, ulcerated, friable lesion in the distal esophagus. A biopsy of the lesion demonstrated an invasive, moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma. Of note, mutations in the Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) and TP53 genes, as well as PD-L1, were revealed.

The final diagnosis: a paraneoplastic syndrome caused by an esophageal adenocarcinoma, which mimicked adult-onset Still’s disease.

Discussion

Figure 2. Endoscopy findings reveal distal esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Adult-onset Still’s disease is an inflammatory disorder characterized by leukocytosis, elevated ferritin levels, intermittent fevers and transient rashes.1 The Yamaguchi criteria are commonly used to assist with diagnosis. Fever for longer than one week, arthralgias or arthritis for two weeks, evanescent skin eruption and leukocytosis (10,000/µL or greater with 80% or greater neutrophils) are the major criteria used for the diagnosis of adult-onset Still’s disease. Absence of rheumatoid factor and anti-nuclear antibodies, and the presence of lymphadenopathy, pharyngitis, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly and abnormal aminotransferases are minor criteria that can be used to fulfill a diagnosis of adult-onset Still’s disease.

The exclusion of other illnesses is necessary to establish a diagnosis of adult-onset Still’s disease.1 Cancer and infection can mimic its clinical manifestations.3

Mutations in the KRAS gene have been reported, with lower overall survival in patients with colorectal cancer.4 KRAS mutations have also been associated with treatment resistance.5 The significance of the PD-L1 mutation is less clear. Hsieh et al. showed that overexpression of PD-L1 in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma had a better overall survival after esophagectomy.6 The TP-53 mutation is associated esophageal and gastric carcinogenesis.7

Back to our patient: After initial treatment with intravenous methylprednisolone, our patient was treated with a gradual steroid taper; three weeks later his ferritin had decreased to 551 ng/mL (RR: 8–388), and his ESR had decreased to 51 mm/hr (RR: 0–20).

Interestingly, there is a case report of a patient with adult-onset Still’s disease who was diagnosed with an esophageal cancer nine months after the onset of Still’s disease.8 Shibuya et al. presented the case of a 77-year-old man who presented with adult-onset Still’s disease and had been placed on tapering doses of prednisolone. During the steroid taper, the patient developed recurrent fever, arthritis and rash. On re-evaluation, the patient was found to have esophageal cancer.8 This case highlighted that esophageal cancer may mimic adult-onset Still’s disease.

Our own case bears some similarities to this presentation. Our patient’s esophageal cancer was discovered shortly after he presented with adult-onset Still’s disease. Likewise, his rash and arthralgias worsened with lower steroid doses. In this regard, our patient presented in a fashion more typical of a paraneoplastic syndrome.

In 2015, Sun et al. described cases of malignancy associated with atypical presentations of adult-onset Still’s disease.9 Thirty-one case reports described patients who satisfied the Yamaguchi criteria (for a total of 31 patients), and adult-onset Still’s disease-like symptoms were reported in patients with multiple forms of malignancy. A diagnosis of a malignancy was established after a diagnosis of adult-onset Still’s disease in 13 of the 31 cases.

The condition most strongly associated with adult-onset Still’s disease-like symptoms was lymphoma (eight of the 31 patients).9,10 Breast cancer had the second strongest association (six of the 31 patients).9 Papillary subtypes of thyroid cancer were reported as well.9,11 With regard to the gastrointestinal tract, one malignancy of the esophagus and one malignancy involving the rectum were documented.9

The single case of esophageal cancer noted in this review was the patient presentation documented by Shibuya et al. in 2003.8 One patient was diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma.9,12 The cutaneous findings associated with the adult-onset Still’s disease presentations were consistent with evanescent rashes in all but two of the 31 cases.9

According to Sun et al., the first reports of adult-onset Still’s disease-like symptoms in the setting of malignancy were described in 1988.9,13 The first patient was diagnosed with myeloproliferative syndrome, but had initially presented with fever, arthritis, leukocytosis and a transient rash. The second patient also initially presented with fever, arthritis and a temporary rash, but was later discovered to be harboring a laryngeal carcinoma.13

Charda et al. performed extensive chart reviews of patients aged 18 and older who were diagnosed with adult-onset Still’s disease or an adult-onset Still’s disease-type syndrome.14 Nine patients with adult-onset Still’s disease were identified and followed for 25 months after initial diagnosis. One developed Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and another had acute myelogenous leukemia with concurrent non-squamous cell lung carcinoma. This study suggested a relationship between adult-onset Still’s disease and malignancy needs to be explored and further supports the hypothesis that our patient’s initial presentation may have had a correlation with malignancy.