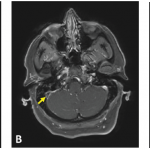

An aphthous lesion and reddish-brown raised plaques on the anterior chest and bilateral upper extremities are pictured.

Courtesy Felicia Yang, MD

Her laboratory evaluation revealed worsening anemia, thrombocytosis, neutrophilia and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein. Her electrolytes and renal function were within normal limits. Hepatitis B and C serologies and a QuantiFERON-TB Gold test for tuberculosis were negative. No significant abnormalities were found on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies.

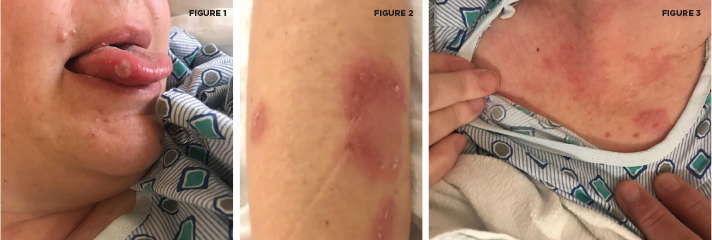

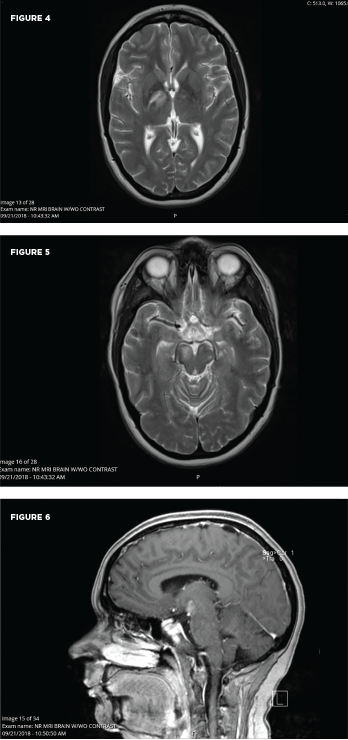

An MRI showed new signal abnormality and enhancement in the bilateral internal capsules and extending into the brainstem (see Figures 4–6).

A dermatologist was consulted to perform a skin biopsy, which showed superficial and deep lymphocytic and histiocytic inflammatory infiltrate with a superficial interstitial histiocytic and neutrophilic infiltrate with leukocytoclasis.

The patient was diagnosed with neuro-Behçet’s disease and treated with intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone for three days. A detailed ophthalmologic exam revealed no evidence of ocular involvement. After completing the course of IV methylprednisolone, the patient was transitioned to 40 mg of prednisone daily and 50 mg of azathioprine daily.

She was discharged, and the azathioprine was titrated up to 150 mg daily during her follow-up visits.

Diagnosis

These MRI scans reveal new signal abnormality and enhancement in the bilateral internal capsules, extending into the brainstem.

University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center

Two sets of diagnostic criteria have been proposed for Behçet’s: the International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease criteria and the International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease (ICBD; see Tables 1 & 2). Both include as a primary criterion the presence of recurrent oral ulcerations, including minor or major aphthous ulcers or herpetiform ulcers occurring at least three times in a 12-month period. Also included are recurrent genital ulcers, eye lesions, skin lesions or a positive pathergy test.1

A diagnosis of neuro-Behçet’s disease requires a diagnosis of systemic Behçet’s disease with the presence of neurologic symptoms supported by imaging or cerebrospinal fluid analysis.1,2 Because other neurologic illnesses can have a similar presentation, it is important to exclude other potential causes.

Between 2.5% and 50% of patients with Behçet’s disease exhibit neurologic involvement several years into the disease course.3 The wide range is presumably based on such factors as geography, ethnicity and inclusion criteria for neurologic disease. In 1985, a review of Japanese autopsy registry data by Lakhanpal et al. showed that of 170 autopsies of Behçet’s disease patients, 20% showed pathological evidence of brain involvement.5

Neurologic manifestations as the first sign of disease are rare, which makes the diagnosis in patients without other symptoms of Behçet’s disease difficult.3 A literature review revealed three prior series that document neurologic manifestations as the first sign of disease.

The first, by Akman-Demir et al. in 1999, showed that of 200 Turkish patients with neuro-Behçet’s disease, only six had neurologic symptoms as the first manifestation of Behçet’s disease.6 The other two studies had smaller populations: In 2010, Riera-Mestre et al. reported that 13 of 20 Spanish patients with Behçet’s disease presented with neurologic symptoms as the first manifestation of disease, and in 2012, Dutra et al. reported that six of 36 Brazilian patients with Behçet’s disease presented with neurologic sypmptoms as the first manifestation of disease.7,8

A diagnosis of neuro-Behçet’s disease generally requires patients meet the diagnostic criteria previously mentioned for Behçet’s disease (i.e., the ISG or ICBD criteria). Thus, only about 10% of patients are considered to have true neuro-Behçet’s disease.3 These patients have primary neurologic involvement; neurologic symptoms are a direct consequence of Behçet’s disease affecting the central nervous system (CNS). Secondary neurologic involvement makes up the greater portion of the previously cited 2.5–50%, in which neurologic symptoms are due to systemic involvement of Behçet’s disease, for example, cardiac emboli or secondary to toxicity of treatment, such as peripheral neuropathy caused by medications.3,9,10

Neuro-Behçet’s disease can occur as either parenchymal or non-parenchymal disease. Parenchymal disease involves the brainstem, cerebral hemispheres, cerebellum or the diencephalon and makes up approximately 80% of neuro-Behçet’s disease cases. Non-parenchymal disease includes cerebral venous thrombosis, intracranial hypertension syndrome, acute meningeal syndrome and, uncommonly, stroke due to arterial thrombosis, dissection or aneurysm. Most pediatric cases of neuro-Behçet’s disease are non-parenchymal. In such cases, the superior sagittal sinus and the transverse sinus are most frequently involved, and this tends to occur in a progressive manner, evolving over weeks to months. Non-parenchymal disease occurs earlier in the course of disease compared with parenchymal neuro-Behçet’s disease.1,3

Neuroimaging is an important part of patient assessment in cases of possible neuro-Behçet’s. MRI is more sensitive and specific than CT in showing reversible inflammatory parenchymal lesions. Multiple case reports have documented parenchymal disease initially being misclassified as aseptic meningitis based on normal CT scans.2 Lesions are generally located within the brainstem, occasionally extending into the diencephalon and, less often, within the periventricular and subcortical white matter. Brainstem atrophy and third ventricle enlargement have been noted on serial MRIs of patients with progressive or relapsing neuro-Behçet’s disease.

Table 1: The International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease (ICBD)

| Signs/Symptoms | Points |

|---|---|

| Ocular Lesions | 2 |

| Oral aphthosis | 2 |

| Genital aphthosis | 2 |

| Skin lesions | 1 |

| Neurologic manifestations | 1 |

| Vascular manifestations | 1 |

| Positive pathergy test | 1 |

| Note: Four or more points are necessary for a patient to meet the criteria for Behçet’s disease. | |

| Source: International Team for the Revision of the International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease (ITR-ICBD). The International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease (ICBD): A collaborative study of 27 countries on the sensitivity and specificity of the new criteria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014 Mar;28(3):338–347. |