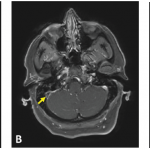

Some case reports have also noted mass-like lesions mimicking brain tumors. This may be due to acute inflammatory edema, and some documentation exists of such lesions resolving with intravenous methylprednisolone. However, in some cases, mass-like lesions have led to severe initial and long-term disability. The prevalence remains low, with one study noting mass-like lesions found in only 1.8% of 275 patients with neuro-Behçet’s disease.11 Lesions on T1 MRI sequences may appear hypo- or isointense and hyperintense on T2- and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences.12

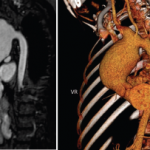

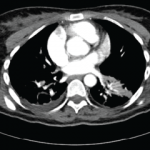

Magnetic resonance venography is the preferred method to diagnose non-parenchymal neuro-Behçet’s disease, although T1 and T2 images are more commonly used. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) can be used to demonstrate vasculitis, dissection or aneurysms, although these are not commonly found. Fatal bleeding during arterial injection of contrast was reported in a patient with a basilar artery aneurysm, and it is thought that vascular inflammation due to the disease itself may increase the risk of bleeding.1,12

A diagnosis of neuro-Behçet’s disease requires a diagnosis of systemic Behçet’s disease with the presence of neurologic symptoms supported by imaging or cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

Cerebrospinal fluid studies may show elevated white blood cell (WBC) count and modestly elevated protein levels. In the acute stage of disease, a neutrophilic predominance is likely. In later stages of disease, lymphocytes commonly become the dominant cell type. CSF immunoglobulin G (IgG) may be elevated, but oligoclonal bands are usually negative (seen in less than 20%). CSF levels of IL-6, IL-8 and IL-33 have been found to correlate with neuro-Behçet’s disease activity, prognosis and response to treatment.2,3 With non-parenchymal neuro-Behçet’s disease, CSF opening pressure is often elevated, but other parameters are generally within normal ranges.1-3

Clinical Presentation

The manifestations of neuro-Behçet’s disease depend on parenchymal and non-parenchymal disease. The presentation of parenchymal disease varies widely. Symptoms of parenchymal neuro-Behçet’s disease may include headaches, fevers, weakness, spasticity, hyperreflexia, oculoparesis/uveitis, facial palsy, dysarthria, memory disturbance, psychosis, cognitive dysfunction, depression, aphasia, neglect, sensory deficits, hemiplegia and seizures. Non-parenchymal disease presents with headaches, papilledema, nausea, vomiting, hyperreflexia and cranial nerve VI palsy.1-3,13-15

The protean manifestations of neuro-Behçet’s disease lead to a wide differential diagnosis. One key consideration is multiple sclerosis (MS). Key differences between the two diseases exist. In neuro-Behçet’s disease, brainstem involvement is common, with extension to basal ganglia and diencephalic regions, whereas MS has a clear preference for the periventricular area and corpus callosum. Cerebral loss is often seen in neuro-Behçet’s disease and not in MS; sensory dysfunction, optic neuritis, internuclear ophthalmoplegia and spinal cord involvement are more common in MS. In addition, CSF from patients with MS often demonstrates oligoclonal bands.

Table 2: The International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease Criteria

| Mandatory Criteria (required) | Minor Criteria (must meet at least 2) |

|---|---|

| Recurrent oral apthous ulcers (at least 3 in a 12-month period) | Recurrent genital ulcers |

| Eye lesions | |

| Skin lesions | |

| Source: International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease. Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. Lancet. 1990 May 5;335(8697):1078–1080. |