CNS infections, caused by syphilis, viruses, fungi and bacteria, should be ruled out when evaluating a patient for neuro-Behçet’s disease. CSF findings consistent with infection include an elevated opening pressure, a decreased glucose (bacterial), elevated white blood count and positive cultures.

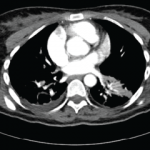

In neurosarcoidosis, isolated cranial nerve (CN) neuropathies are common, most often affecting CN VII, as are noncaseating granulomas, hilar lymphadenopathy on chest X-ray, and elevated angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) and calcium levels.1,15

Autoimmune or inflammatory diagnoses that should be ruled out include systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome and CNS vasculitis. CNS vasculitis usually presents with multiple infarcts that involve cortical areas in the absence of systemic symptoms.

Other rare disorders to consider include Vogt-Koyanagi Harada syndrome, reactive arthritis, Eales disease, Cogan syndrome, Susac syndrome and neuro-Sweet disease. All have ocular involvement but can be differentiated on detailed ophthalmologic exams. Lastly, it is also important to consider malignancy, such as CNS lymphoma or glioma, or cerebrovascular accident (CVA) in the differential.15

Treatment

In 2018, EULAR published treatment guidelines for neuro-Behçet’s disease. These were level IIIC recommendations because they were supported only by uncontrolled observational studies.16 In the case of an acute attack, it is recommended to start the patient on 1 g of intravenous methylprednisolone daily for five to 10 days. Following this, oral prednisolone or prednisone can be given as 1 mg/kg/day for one month, tapered by 5 to 10 mg every 10 to 15 days. This regimen can be adjusted based on clinical judgment. Treatment with corticosteroids has not been shown to prevent relapses.1,3,16

Additional immunosuppressives are recommended for patients who fail to respond to steroids or have frequent relapses. They can be started at the same time as corticosteroids for an acute attack. First-line therapy is azathioprine with a target dose of 2–3 mg/kg. Alternatives include methotrexate 12.5 to 25 mg/week, mycophenolate 2–3 g/day and cyclophosphamide 500–1000 mg/m2 IV for 6–12 months.

TNF-α inhibitors have also been used as steroid-sparing agents to prevent relapse. The most commonly used TNF-α inhibitors include infliximab, etanercept and adalimumab.1,3,15,17

Some case reports describe infliximab being successful in otherwise refractory and aggressive cases. One case report presented a patient treated with golimumab after having relapse with azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, infliximab and tocilizumab.18

Anti-IL-1 antibody therapy, such anakinra or canakinumab, has been shown to be highly effective in cases of ocular involvement.

In rare instances, tocilizumab has been used in neuro-Behçet’s disease. EULAR guidelines recommended against use of cyclosporin A because observational studies have shown that it may increase the risk of CNS symptoms due to neurotoxic effects.3,16

In two cases of severe progressive neuro-Behçet’s disease, the patients underwent autologous peripheral hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. At 48-month follow-up, they were both off all medications and one patient showed mild improvement in neurologic status and disability.3,4

In non-parenchymal disease, initial therapy is also high-dose corticosteroids. 2018 EULAR guidelines state no benefit is seen with the addition of immunosuppressives in the first episode of cerebral venous thrombosis.16 Only small studies and case reports show the benefit of immunosuppression in reducing the rate of relapse in non-parenchymal neuro-Behçet’s disease. A cohort study by Desbois et al. reported on 76 patients with relapse of thrombosis. Eight of these patients had been treated with immunosuppressants and 68 had not been treated with immunosuppressive agents. The immunosuppressive agents used included cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, methotrexate and TNF inhibitors.14,19

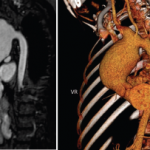

Anticoagulation in non-parenchymal neuro-Behçet’s disease is controversial due to concerns over increased bleeding risk. Neuro-Behçet’s disease may have the potential to increase the prevalence of intracranial aneurysms, and a thrombus may be inherently tightly adherent to the vessel wall due to inflammation. In a retrospective study by Shi et al., 20 of 21 patients received anticoagulation without any adverse effects. One patient had a subarachnoid hemorrhage and hemoptysis.14,20

Desbois et al. published a study of 291 patients treated with anticoagulants, of which seven had a bleeding complication. These complications included gastrointestinal hemorrhage, subdural hematoma, lower limb hematoma, perirenal hematoma or hemoptysis.19 Per the 2018 EULAR guidelines, anticoagulants may be added for a short duration and the decision for anticoagulation is left to clinical judgment.16 Daily aspirin has been suggested as an alternative.1

Two-thirds of patients with neuro-Behçet’s disease recover without significant neurologic deficits after the initial attack.1,2 Nonetheless, the rate of relapse is high. Some 50% of patients have at least one relapse: 35% in five years and 47% in seven years. About 30% of patients have progressive neurologic decline despite treatment. At 10 years, 78% of patients have at least mild neurologic disability and up to 45% may have severe neurologic disability. Poor prognosic factors include HLA-B*51 carriers, elevated WBC or protein in CSF studies, involvement of brainstem, more than two attacks or relapse during treatment with steroids. HLA-B*51 carriers have been noted to have more aggressive disease leading to a relapse rate of approximately 51% over a seven-year follow-up period. Patients with non-parenchymal neuro-Behçet’s disease have a more benign course and are less likely to relapse.1,2

Zeba Faroqui, MD, obtained her Doctor of Medicine from SUNY Downstate College of Medicine, New York. She completed her rheumatology fellowship at Case Western School of Medicine/University Hospitals in Cleveland. She now practices in Plainview, N.Y.

Zeba Faroqui, MD, obtained her Doctor of Medicine from SUNY Downstate College of Medicine, New York. She completed her rheumatology fellowship at Case Western School of Medicine/University Hospitals in Cleveland. She now practices in Plainview, N.Y.

References

- Miller JJ, Venna N, Siva A. Neuro-Behçet disease and autoinflammatory disorders. Sem Neurol. 2014 Sep;34(4):437–443.

- Saip S, Akman-Demir G, Siva A. Neuro-Behçet syndrome. In Biller J, Ferro JM (Eds). Neurologic Aspects of Systemic Disease Part III (pp 1703–1724). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier. 2014.

- Kürtüncü M, Tüzün E, Akman-Demir G. Behçet’s disease and nervous system involvement. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2016 May;18(5):19.

- De Cata A, Intiso D, Bernal M, et al. Prolonged remission in neuro-Behcet disease following autologous transplantation. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. Jan–Mar 2007;20(1):91–96.

- Lakhanpal S, Tani K, Lie JT, et al. Pathologic features of Behçet’s syndrome: A review of Japanese autopsy registry data. Hum Pathol. 1985 Aug;16:790–795.

- Akman-Demir G, Serdaroglu P, Tasçi B. Clinical patterns of neurological involvement in Behçet’s disease: Evaluation of 200 patients. The Neuro-Behçet Study Group. Brain. 1999;122(pt 11):2171–2182.

- Dutra LA, Gonçalves CR, Braga-Neto P, et al. Atypical manifestations in Brazilian patients with neuro-Behçet’s disease. J Neurol. 2012 Jun;259(6):1159–1165.

- Riera-Mestre A, Martínez-Yelamos S, Martínez-Yelamos A, et al. Clinicopathologic features and outcomes of neuro-Behçet’s disease in Spain: A study of 20 patients. Eur J Int Med. 2010 Dec:21(6): 536–541.

- Ozyurt S, Sfikakis P, Siva A, et al. Neuro-Behçet’s disease—Clinical features, diagnosis and differential diagnosis. Eur Neurol Rev. 2018;13(2):93–97.

- Siva A, Saip S. The spectrum of nervous system involvement in Behçet’s syndrome and its differential diagnosis. J Neurol. 2009 Apr;256(4):513–529.

- Kir S, Akyol L, Ozgen M, et al. Ptosis and mass like lesions in Behçet’s disease: A rare presentation. Arch Rheumatol. 2017 Oct;33(2)221–224.

- Saito K, Watanabe T, Toru S. Multiple hemorrhagic cerebral cortical lesions in neuro-Behçet’s disease. Intern Med. 2017 Sep 1;56(17): 2377–2378.

- Othmon K, Tajudin A. Severe panuveitis in neuro-Behcet disease in Malaysia: A case series. Int Med Case Rep J. 2017 Feb 7;10:35–40.

- Lyons J, Nevares A. Case report: A Behçet’s patient develops cerebral venous sinus thrombi. The Rheumatologist, 2018 Dec 17:42–43.

- Caruso P, Moretti R. Focus on neuro-Behçet’s disease: A review. Neurol India. Nov–Dec 2018;66(6):1619–1628.

- Hatemi G, Christensen R, Bang D, et al. 2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of Behçet’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Jun;77(6):808–818.

- Kalra S, Silman A, Akman-Demir G, et al. Diagnosis and management of neuro-Behçet’s disease: International consensus recommendations. J Neurol. 2014 Sep:261(9):1662–1676.

- London F, Pesch V. Which treatment strategies for highly refractory forms of neuro-Behçet’s disease? Mult Scler. 2017 Oct;23(3_suppl):680–975 (ePoster 1289).

- Desbois AC, Wechsler B, Resche-Rigon M, et al. Immunosuppressants reduce venous thrombosis relapse in Behçet’s disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2012 Aug;64(8):2753–2760.

- Shi J, Huang X, Li G, et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in Behçet’s disease: A retrospective case-control study. Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Jan;37(1):51–57.