A 44-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with bifrontal headaches that had started approximately one month earlier. She was diagnosed with migraines and discharged home. Three days later, the patient returned to the emergency department upon recurrence of her headaches, and this time she also reported abnormal leg movements. A computerized tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head were unrevealing.

The patient’s symptoms appeared to be due to a transient ischemic attack, and she was treated with warfarin with instructions to follow up with a neurologist. On follow-up, the neurologist ordered a repeat MRI of the brain. While at the MRI facility a few days later, the patient began to have severe headaches again and was sent back to the emergency department. The MRI showed nonspecific white matter changes from the midbrain to the thalamus. She was started on 1 g of intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone and admitted to the hospital.

On further investigation, the patient reported that she had recurrent oral ulcers once per month. The lesions were singular in nature and had never appeared in clusters. A rheumatologist was consulted to evaluate for Behçet’s disease, but the evidence was felt to be insufficient; she did not report any changes in vision, genital ulcers, joint pain or morning stiffness. She had no evidence of uveitis, oral ulcers, genital lesions, rashes or pathergy on exam.

A positron emission tomography scan revealed a calcified granuloma in the left lower lobe of the lung. This finding prompted the neurologist to consider neurosarcoidosis. The patient was discharged on 60 mg of prednisone daily with plans for steroid taper managed by the neurologist.

On follow-up with the neurologist three months later, the patient was on 26 mg of prednisone daily and was doing well.

Two months after that visit, she presented to the emergency department again, this time reporting two weeks of difficulty speaking and an unsteady gait. She reported new skin lesions over her chest and both arms, which had developed within the prior month, and an increased frequency of oral ulcers. She also complained of confusion and an inability to focus at work. She denied arthritic symptoms at the time of presentation but did report right ankle pain and swelling approximately two to three weeks prior. By this time, she was on 6 mg of prednisone daily.

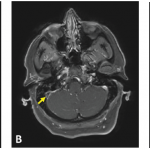

Her physical exam was significant for oral aphthous lesions, painful erythematous nodules over the left upper lateral and medial shin, and reddish-brown raised plaques on her anterior chest and both upper extremities (see Figures 1–3). She had swelling and tenderness over her proximal interphalangeal joints and metacarpophalangeal joints of both hands, as well as synovitis in both ankles. She was speaking with a lisp, had an unsteady gait and spastic choreiform-like movements of both legs. No sensory deficits were experienced, and her strength remained intact throughout the exam.

An aphthous lesion and reddish-brown raised plaques on the anterior chest and bilateral upper extremities are pictured.

Courtesy Felicia Yang, MD

Her laboratory evaluation revealed worsening anemia, thrombocytosis, neutrophilia and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein. Her electrolytes and renal function were within normal limits. Hepatitis B and C serologies and a QuantiFERON-TB Gold test for tuberculosis were negative. No significant abnormalities were found on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies.

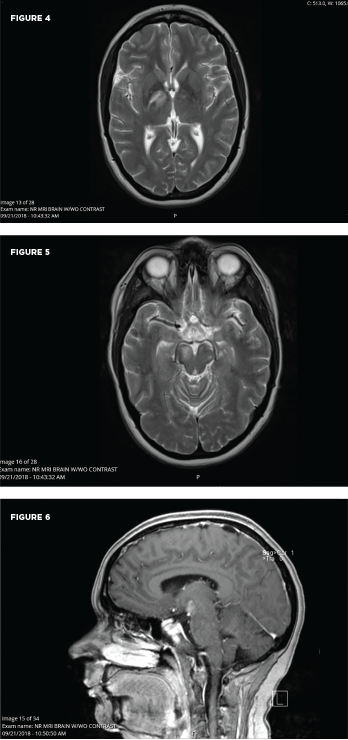

An MRI showed new signal abnormality and enhancement in the bilateral internal capsules and extending into the brainstem (see Figures 4–6).

A dermatologist was consulted to perform a skin biopsy, which showed superficial and deep lymphocytic and histiocytic inflammatory infiltrate with a superficial interstitial histiocytic and neutrophilic infiltrate with leukocytoclasis.

The patient was diagnosed with neuro-Behçet’s disease and treated with intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone for three days. A detailed ophthalmologic exam revealed no evidence of ocular involvement. After completing the course of IV methylprednisolone, the patient was transitioned to 40 mg of prednisone daily and 50 mg of azathioprine daily.

She was discharged, and the azathioprine was titrated up to 150 mg daily during her follow-up visits.

Diagnosis

These MRI scans reveal new signal abnormality and enhancement in the bilateral internal capsules, extending into the brainstem.

University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center

Two sets of diagnostic criteria have been proposed for Behçet’s: the International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease criteria and the International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease (ICBD; see Tables 1 & 2). Both include as a primary criterion the presence of recurrent oral ulcerations, including minor or major aphthous ulcers or herpetiform ulcers occurring at least three times in a 12-month period. Also included are recurrent genital ulcers, eye lesions, skin lesions or a positive pathergy test.1

A diagnosis of neuro-Behçet’s disease requires a diagnosis of systemic Behçet’s disease with the presence of neurologic symptoms supported by imaging or cerebrospinal fluid analysis.1,2 Because other neurologic illnesses can have a similar presentation, it is important to exclude other potential causes.

Between 2.5% and 50% of patients with Behçet’s disease exhibit neurologic involvement several years into the disease course.3 The wide range is presumably based on such factors as geography, ethnicity and inclusion criteria for neurologic disease. In 1985, a review of Japanese autopsy registry data by Lakhanpal et al. showed that of 170 autopsies of Behçet’s disease patients, 20% showed pathological evidence of brain involvement.5

Neurologic manifestations as the first sign of disease are rare, which makes the diagnosis in patients without other symptoms of Behçet’s disease difficult.3 A literature review revealed three prior series that document neurologic manifestations as the first sign of disease.

The first, by Akman-Demir et al. in 1999, showed that of 200 Turkish patients with neuro-Behçet’s disease, only six had neurologic symptoms as the first manifestation of Behçet’s disease.6 The other two studies had smaller populations: In 2010, Riera-Mestre et al. reported that 13 of 20 Spanish patients with Behçet’s disease presented with neurologic symptoms as the first manifestation of disease, and in 2012, Dutra et al. reported that six of 36 Brazilian patients with Behçet’s disease presented with neurologic sypmptoms as the first manifestation of disease.7,8

A diagnosis of neuro-Behçet’s disease generally requires patients meet the diagnostic criteria previously mentioned for Behçet’s disease (i.e., the ISG or ICBD criteria). Thus, only about 10% of patients are considered to have true neuro-Behçet’s disease.3 These patients have primary neurologic involvement; neurologic symptoms are a direct consequence of Behçet’s disease affecting the central nervous system (CNS). Secondary neurologic involvement makes up the greater portion of the previously cited 2.5–50%, in which neurologic symptoms are due to systemic involvement of Behçet’s disease, for example, cardiac emboli or secondary to toxicity of treatment, such as peripheral neuropathy caused by medications.3,9,10

Neuro-Behçet’s disease can occur as either parenchymal or non-parenchymal disease. Parenchymal disease involves the brainstem, cerebral hemispheres, cerebellum or the diencephalon and makes up approximately 80% of neuro-Behçet’s disease cases. Non-parenchymal disease includes cerebral venous thrombosis, intracranial hypertension syndrome, acute meningeal syndrome and, uncommonly, stroke due to arterial thrombosis, dissection or aneurysm. Most pediatric cases of neuro-Behçet’s disease are non-parenchymal. In such cases, the superior sagittal sinus and the transverse sinus are most frequently involved, and this tends to occur in a progressive manner, evolving over weeks to months. Non-parenchymal disease occurs earlier in the course of disease compared with parenchymal neuro-Behçet’s disease.1,3

Neuroimaging is an important part of patient assessment in cases of possible neuro-Behçet’s. MRI is more sensitive and specific than CT in showing reversible inflammatory parenchymal lesions. Multiple case reports have documented parenchymal disease initially being misclassified as aseptic meningitis based on normal CT scans.2 Lesions are generally located within the brainstem, occasionally extending into the diencephalon and, less often, within the periventricular and subcortical white matter. Brainstem atrophy and third ventricle enlargement have been noted on serial MRIs of patients with progressive or relapsing neuro-Behçet’s disease.

Table 1: The International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease (ICBD)

| Signs/Symptoms | Points |

|---|---|

| Ocular Lesions | 2 |

| Oral aphthosis | 2 |

| Genital aphthosis | 2 |

| Skin lesions | 1 |

| Neurologic manifestations | 1 |

| Vascular manifestations | 1 |

| Positive pathergy test | 1 |

| Note: Four or more points are necessary for a patient to meet the criteria for Behçet’s disease. | |

| Source: International Team for the Revision of the International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease (ITR-ICBD). The International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease (ICBD): A collaborative study of 27 countries on the sensitivity and specificity of the new criteria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014 Mar;28(3):338–347. |

Some case reports have also noted mass-like lesions mimicking brain tumors. This may be due to acute inflammatory edema, and some documentation exists of such lesions resolving with intravenous methylprednisolone. However, in some cases, mass-like lesions have led to severe initial and long-term disability. The prevalence remains low, with one study noting mass-like lesions found in only 1.8% of 275 patients with neuro-Behçet’s disease.11 Lesions on T1 MRI sequences may appear hypo- or isointense and hyperintense on T2- and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences.12

Magnetic resonance venography is the preferred method to diagnose non-parenchymal neuro-Behçet’s disease, although T1 and T2 images are more commonly used. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) can be used to demonstrate vasculitis, dissection or aneurysms, although these are not commonly found. Fatal bleeding during arterial injection of contrast was reported in a patient with a basilar artery aneurysm, and it is thought that vascular inflammation due to the disease itself may increase the risk of bleeding.1,12

A diagnosis of neuro-Behçet’s disease requires a diagnosis of systemic Behçet’s disease with the presence of neurologic symptoms supported by imaging or cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

Cerebrospinal fluid studies may show elevated white blood cell (WBC) count and modestly elevated protein levels. In the acute stage of disease, a neutrophilic predominance is likely. In later stages of disease, lymphocytes commonly become the dominant cell type. CSF immunoglobulin G (IgG) may be elevated, but oligoclonal bands are usually negative (seen in less than 20%). CSF levels of IL-6, IL-8 and IL-33 have been found to correlate with neuro-Behçet’s disease activity, prognosis and response to treatment.2,3 With non-parenchymal neuro-Behçet’s disease, CSF opening pressure is often elevated, but other parameters are generally within normal ranges.1-3

Clinical Presentation

The manifestations of neuro-Behçet’s disease depend on parenchymal and non-parenchymal disease. The presentation of parenchymal disease varies widely. Symptoms of parenchymal neuro-Behçet’s disease may include headaches, fevers, weakness, spasticity, hyperreflexia, oculoparesis/uveitis, facial palsy, dysarthria, memory disturbance, psychosis, cognitive dysfunction, depression, aphasia, neglect, sensory deficits, hemiplegia and seizures. Non-parenchymal disease presents with headaches, papilledema, nausea, vomiting, hyperreflexia and cranial nerve VI palsy.1-3,13-15

The protean manifestations of neuro-Behçet’s disease lead to a wide differential diagnosis. One key consideration is multiple sclerosis (MS). Key differences between the two diseases exist. In neuro-Behçet’s disease, brainstem involvement is common, with extension to basal ganglia and diencephalic regions, whereas MS has a clear preference for the periventricular area and corpus callosum. Cerebral loss is often seen in neuro-Behçet’s disease and not in MS; sensory dysfunction, optic neuritis, internuclear ophthalmoplegia and spinal cord involvement are more common in MS. In addition, CSF from patients with MS often demonstrates oligoclonal bands.

Table 2: The International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease Criteria

| Mandatory Criteria (required) | Minor Criteria (must meet at least 2) |

|---|---|

| Recurrent oral apthous ulcers (at least 3 in a 12-month period) | Recurrent genital ulcers |

| Eye lesions | |

| Skin lesions | |

| Source: International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease. Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. Lancet. 1990 May 5;335(8697):1078–1080. |

CNS infections, caused by syphilis, viruses, fungi and bacteria, should be ruled out when evaluating a patient for neuro-Behçet’s disease. CSF findings consistent with infection include an elevated opening pressure, a decreased glucose (bacterial), elevated white blood count and positive cultures.

In neurosarcoidosis, isolated cranial nerve (CN) neuropathies are common, most often affecting CN VII, as are noncaseating granulomas, hilar lymphadenopathy on chest X-ray, and elevated angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) and calcium levels.1,15

Autoimmune or inflammatory diagnoses that should be ruled out include systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome and CNS vasculitis. CNS vasculitis usually presents with multiple infarcts that involve cortical areas in the absence of systemic symptoms.

Other rare disorders to consider include Vogt-Koyanagi Harada syndrome, reactive arthritis, Eales disease, Cogan syndrome, Susac syndrome and neuro-Sweet disease. All have ocular involvement but can be differentiated on detailed ophthalmologic exams. Lastly, it is also important to consider malignancy, such as CNS lymphoma or glioma, or cerebrovascular accident (CVA) in the differential.15

Treatment

In 2018, EULAR published treatment guidelines for neuro-Behçet’s disease. These were level IIIC recommendations because they were supported only by uncontrolled observational studies.16 In the case of an acute attack, it is recommended to start the patient on 1 g of intravenous methylprednisolone daily for five to 10 days. Following this, oral prednisolone or prednisone can be given as 1 mg/kg/day for one month, tapered by 5 to 10 mg every 10 to 15 days. This regimen can be adjusted based on clinical judgment. Treatment with corticosteroids has not been shown to prevent relapses.1,3,16

Additional immunosuppressives are recommended for patients who fail to respond to steroids or have frequent relapses. They can be started at the same time as corticosteroids for an acute attack. First-line therapy is azathioprine with a target dose of 2–3 mg/kg. Alternatives include methotrexate 12.5 to 25 mg/week, mycophenolate 2–3 g/day and cyclophosphamide 500–1000 mg/m2 IV for 6–12 months.

TNF-α inhibitors have also been used as steroid-sparing agents to prevent relapse. The most commonly used TNF-α inhibitors include infliximab, etanercept and adalimumab.1,3,15,17

Some case reports describe infliximab being successful in otherwise refractory and aggressive cases. One case report presented a patient treated with golimumab after having relapse with azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, infliximab and tocilizumab.18

Anti-IL-1 antibody therapy, such anakinra or canakinumab, has been shown to be highly effective in cases of ocular involvement.

In rare instances, tocilizumab has been used in neuro-Behçet’s disease. EULAR guidelines recommended against use of cyclosporin A because observational studies have shown that it may increase the risk of CNS symptoms due to neurotoxic effects.3,16

In two cases of severe progressive neuro-Behçet’s disease, the patients underwent autologous peripheral hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. At 48-month follow-up, they were both off all medications and one patient showed mild improvement in neurologic status and disability.3,4

In non-parenchymal disease, initial therapy is also high-dose corticosteroids. 2018 EULAR guidelines state no benefit is seen with the addition of immunosuppressives in the first episode of cerebral venous thrombosis.16 Only small studies and case reports show the benefit of immunosuppression in reducing the rate of relapse in non-parenchymal neuro-Behçet’s disease. A cohort study by Desbois et al. reported on 76 patients with relapse of thrombosis. Eight of these patients had been treated with immunosuppressants and 68 had not been treated with immunosuppressive agents. The immunosuppressive agents used included cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, methotrexate and TNF inhibitors.14,19

Anticoagulation in non-parenchymal neuro-Behçet’s disease is controversial due to concerns over increased bleeding risk. Neuro-Behçet’s disease may have the potential to increase the prevalence of intracranial aneurysms, and a thrombus may be inherently tightly adherent to the vessel wall due to inflammation. In a retrospective study by Shi et al., 20 of 21 patients received anticoagulation without any adverse effects. One patient had a subarachnoid hemorrhage and hemoptysis.14,20

Desbois et al. published a study of 291 patients treated with anticoagulants, of which seven had a bleeding complication. These complications included gastrointestinal hemorrhage, subdural hematoma, lower limb hematoma, perirenal hematoma or hemoptysis.19 Per the 2018 EULAR guidelines, anticoagulants may be added for a short duration and the decision for anticoagulation is left to clinical judgment.16 Daily aspirin has been suggested as an alternative.1

Two-thirds of patients with neuro-Behçet’s disease recover without significant neurologic deficits after the initial attack.1,2 Nonetheless, the rate of relapse is high. Some 50% of patients have at least one relapse: 35% in five years and 47% in seven years. About 30% of patients have progressive neurologic decline despite treatment. At 10 years, 78% of patients have at least mild neurologic disability and up to 45% may have severe neurologic disability. Poor prognosic factors include HLA-B*51 carriers, elevated WBC or protein in CSF studies, involvement of brainstem, more than two attacks or relapse during treatment with steroids. HLA-B*51 carriers have been noted to have more aggressive disease leading to a relapse rate of approximately 51% over a seven-year follow-up period. Patients with non-parenchymal neuro-Behçet’s disease have a more benign course and are less likely to relapse.1,2

Zeba Faroqui, MD, obtained her Doctor of Medicine from SUNY Downstate College of Medicine, New York. She completed her rheumatology fellowship at Case Western School of Medicine/University Hospitals in Cleveland. She now practices in Plainview, N.Y.

Zeba Faroqui, MD, obtained her Doctor of Medicine from SUNY Downstate College of Medicine, New York. She completed her rheumatology fellowship at Case Western School of Medicine/University Hospitals in Cleveland. She now practices in Plainview, N.Y.

References

- Miller JJ, Venna N, Siva A. Neuro-Behçet disease and autoinflammatory disorders. Sem Neurol. 2014 Sep;34(4):437–443.

- Saip S, Akman-Demir G, Siva A. Neuro-Behçet syndrome. In Biller J, Ferro JM (Eds). Neurologic Aspects of Systemic Disease Part III (pp 1703–1724). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier. 2014.

- Kürtüncü M, Tüzün E, Akman-Demir G. Behçet’s disease and nervous system involvement. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2016 May;18(5):19.

- De Cata A, Intiso D, Bernal M, et al. Prolonged remission in neuro-Behcet disease following autologous transplantation. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. Jan–Mar 2007;20(1):91–96.

- Lakhanpal S, Tani K, Lie JT, et al. Pathologic features of Behçet’s syndrome: A review of Japanese autopsy registry data. Hum Pathol. 1985 Aug;16:790–795.

- Akman-Demir G, Serdaroglu P, Tasçi B. Clinical patterns of neurological involvement in Behçet’s disease: Evaluation of 200 patients. The Neuro-Behçet Study Group. Brain. 1999;122(pt 11):2171–2182.

- Dutra LA, Gonçalves CR, Braga-Neto P, et al. Atypical manifestations in Brazilian patients with neuro-Behçet’s disease. J Neurol. 2012 Jun;259(6):1159–1165.

- Riera-Mestre A, Martínez-Yelamos S, Martínez-Yelamos A, et al. Clinicopathologic features and outcomes of neuro-Behçet’s disease in Spain: A study of 20 patients. Eur J Int Med. 2010 Dec:21(6): 536–541.

- Ozyurt S, Sfikakis P, Siva A, et al. Neuro-Behçet’s disease—Clinical features, diagnosis and differential diagnosis. Eur Neurol Rev. 2018;13(2):93–97.

- Siva A, Saip S. The spectrum of nervous system involvement in Behçet’s syndrome and its differential diagnosis. J Neurol. 2009 Apr;256(4):513–529.

- Kir S, Akyol L, Ozgen M, et al. Ptosis and mass like lesions in Behçet’s disease: A rare presentation. Arch Rheumatol. 2017 Oct;33(2)221–224.

- Saito K, Watanabe T, Toru S. Multiple hemorrhagic cerebral cortical lesions in neuro-Behçet’s disease. Intern Med. 2017 Sep 1;56(17): 2377–2378.

- Othmon K, Tajudin A. Severe panuveitis in neuro-Behcet disease in Malaysia: A case series. Int Med Case Rep J. 2017 Feb 7;10:35–40.

- Lyons J, Nevares A. Case report: A Behçet’s patient develops cerebral venous sinus thrombi. The Rheumatologist, 2018 Dec 17:42–43.

- Caruso P, Moretti R. Focus on neuro-Behçet’s disease: A review. Neurol India. Nov–Dec 2018;66(6):1619–1628.

- Hatemi G, Christensen R, Bang D, et al. 2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of Behçet’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Jun;77(6):808–818.

- Kalra S, Silman A, Akman-Demir G, et al. Diagnosis and management of neuro-Behçet’s disease: International consensus recommendations. J Neurol. 2014 Sep:261(9):1662–1676.

- London F, Pesch V. Which treatment strategies for highly refractory forms of neuro-Behçet’s disease? Mult Scler. 2017 Oct;23(3_suppl):680–975 (ePoster 1289).

- Desbois AC, Wechsler B, Resche-Rigon M, et al. Immunosuppressants reduce venous thrombosis relapse in Behçet’s disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2012 Aug;64(8):2753–2760.

- Shi J, Huang X, Li G, et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in Behçet’s disease: A retrospective case-control study. Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Jan;37(1):51–57.