Figure 1

Retroperitoneal fibrosis (RPF) is a rare condition characterized by aberrant fibroinflammatory tissue developing in the retroperitoneum. This disorder was initially called Ormond’s disease. RPF may be idiopathic or secondary to other conditions. Idiopathic RPF is a part of the disease spectrum of chronic periaortitis due to its typical periaortoiliac localization.

Idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis is a relatively uncommon condition characterized by chronic fibroinflammatory proliferation in the retroperitoneum, usually around the infrarenal abdominal aorta and iliac vessels.1,2 It can lead to compression of retroperitoneal structures and a myriad of associated complications, most commonly obstructive uropathy and acute renal injury that can progress to end-stage renal disease.1,2,3

Due to its nonspecific and atypical clinical manifestations, prompt and early diagnosis can be challenging. Prognosis is mainly determined by the impact on renal function and complications from systemic corticosteroids.2

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old Black woman presented to the hospital complaining of nausea, decreased oral intake, diffuse abdominal pain and profuse watery diarrhea, all of which had persisted over a few weeks. She was found to have severe acute kidney injury with a serum creatinine of 9.3 mg/dL. Her baseline serum creatinine had been between 0.7 mg/dL and 0.8 mg/dL in prior years. She did not have a history of abdominal surgery or a family history of renal, oncologic or rheumatic conditions. She had never smoked cigarettes, although she had smoked cannabis for years. A urinalysis did not demonstrate evidence of an active sediment.

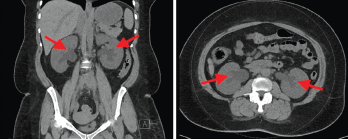

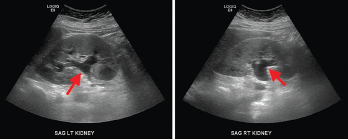

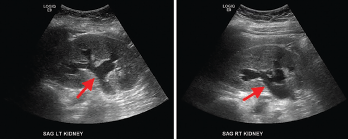

A non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated mild symmetric prominence of the renal pelvises (see Figure 1, top), which was thought to be an incidental finding. A renal ultrasound showed mild bilateral hydronephrosis (see Figure 2, bottom) but the kidneys were found to be of normal size and echogenicity. An evaluation by a nephrologist and a gastroenterologist led to the conclusion that she likely had suffered severe gastrointestinal fluid losses, possibly due to gastroenteritis, which in turn led to acute tubular injury due to severe dehydration.

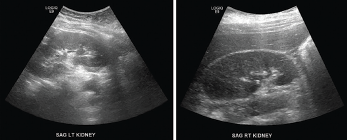

Figure 2. Renal ultrasound, sagittal view, showing mild bilateral hydronephrosis (arrows) with expansion of the renal sinus and calyces with normal renal cortical thickness and echogenicity.

The patient was treated with intravenous hydration and supportive care. Her serum creatinine declined to 1.9 mg/dL, and her gastrointestinal symptoms had resolved by the time of discharge. During this hospitalization, she had also been diagnosed with right-sided Bell’s palsy, for which she received a one-week course of prednisone and valacyclovir. She was also diagnosed with hypertension, which was treated with amlodipine.

A month later, the patient was seen for follow-up by her primary care provider. Laboratory studies showed her serum creatinine level had increased to 5.96 mg/dL; she was asked to return to the hospital for further evaluation. At the time of this second admission, she noted two weeks of fatigue, generalized weakness and constant bilateral flank pain. She had intermittently loose stools but no recurrence of severe abdominal pain or diarrhea. She did not have urinary symptoms or hematuria, and she was not taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or supplements.

The patient’s physical examination was significant for hypertension, tachycardia and non-pitting edema of the left leg. The abdomen was soft, without tenderness or guarding. There was no costovertebral angle tenderness.

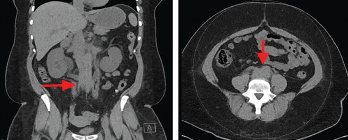

Laboratory findings demonstrated a blood urea nitrogen of 49 mg/dL and a serum creatinine of 11.1 mg/dL. Her urinalysis was unremarkable. A non-contrast CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a retroperitoneal density around the aortic bifurcation. Pelvic masses and mesenteric adenopathy were not seen (see Figure 3). A renal ultrasound (see Figure 4) showed grade 2 bilateral hydronephrosis. A lower extremity ultrasound did not demonstrate evidence of deep venous thrombosis.

Figure 3. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis (left panel: coronal view; right panel: axial view), without intravenous contrast administration, demonstrating increased retroperitoneal density around the aortic bifurcation (arrows).

The patient underwent retrograde pyelography, which confirmed bilateral hydronephrosis. A double-J stent was placed on the left kidney; because of the fishhook configuration of the right ureter, a nephroureteral stent was placed in the right kidney with subsequent conversion into a double-J stent.

Figure 4. Renal ultrasound, sagittal view, showing bilateral grade 2 hydronephrosis (arrows) with normal renal cortical thickness and without focal lesions or nephrolithiasis.

A follow-up ultrasound demonstrated resolution of the obstruction (see Figure 5). Additional laboratory tests (see Table 1), including anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), complement, immunoglobulin levels, serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and immunofixation (IFE), were all unremarkable.

A clinical diagnosis of idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis leading to obstructive uropathy was made, and induction therapy with 1 mg/kg/day of prednisone was initiated. She responded well, and, at the time of discharge, her serum creatinine was 1.3 mg/dL; her improvement in serum creatinine was presumed to be due to stent placement and glucocorticoid therapy.

Figure 5. Renal ultrasound, sagittal view, performed a week after stenting showed complete resolution of hydronephrosis.

Discussion

RPF is a rare inflammatory disease often associated with non-specific clinical features; its etiopathogenesis is poorly understood.1 The overall incidence of RPF is unknown. Previous studies have estimated the incidence of idiopathic RPF at approximately 0.1–1.3 cases/100,000 people/year and the prevalence at approximately 1.4 cases/100,000 people.1 RPF is often diagnosed in patients between the ages of 40 and 60 years. Some studies have shown a 2:1 to 3:1 male predominance.1 It is possible that a higher number of male patients seek medical attention due to the genitourinary symptoms and, therefore, men may be over-represented in these studies.3

The age at the time of diagnosis and the male-to-female ratio have been changing over time. Comparing studies from 1987 and 2009, the age at the time of diagnosis increased from 56 to 64 years and male-to-female ratio increased to 3.3:1.4 Although some studies suggested a higher prevalence among white people than among other races, most of the studies noted no significant difference.

RPF is idiopathic in about two-thirds of cases; in one-third of cases, it is associated with other autoimmune diseases, such as IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD).1 In this patient, the serum IgG4 level was normal; however, serum IgG4 is not a reliable indicator of IgG4-RD because a large proportion of patients with RPF associated with IgG4 RD can have normal IgG4 levels. On the other hand, patients with other inflammatory or proliferative conditions can have elevated levels of serum IgG4.5 Given these uncertainties, the authors cannot excluded the possibility that this patient had IgG4-RD instead of idiopathic RPF.

An association between RPF and other conditions, such as atherosclerotic aortic disease, drugs, infections (mainly bacterial and fungal), malignancy and radiation, has also been identified.3 In a retrospective cohort study of patients with RPF, it was noted that one patient had chronic hepatitis E infection, although causality could not be proved.6 No other data regarding the association between RPF and viral infections was found.

Environmental and genetic factors contribute to disease susceptibility. Tobacco smoke and asbestos exposure are strong risk factors for idiopathic RPF. Exposure to asbestos in a smoker is associated with doubling the risk of RPF.7 This susceptibility involves a CD4+ T cell-mediated immune response, which causes proliferation of B cells and fibroblasts in the periaortic retroperitoneum. The main genetic association is with HLA-DRB1*03, which has been associated with other autoimmune diseases.2

Local and systemic production of interleukin (IL) 6 and Th2 cytokines have been demonstrated in idiopathic RPF and RPF found in association with IgG4-RD.8 No data have been found linking cannabinoid use with the development of retroperitoneal fibrosis.

The most common manifestations of RPF include pain in the lower back, abdomen or flank and lower extremity edema due to inferior vena cava or lymphatic compression.1,3 More than 50% of male patients exhibit testicular symptoms, including testicular pain, with or without hydrocele, varicocele or both; these are thought to occur due to encasement of the spermatic vein, retrograde ejaculation and erectile dysfunction.3

Less common features include claudication due to compromise of the arterial circulation in the lower extremities and abdominal pain due to mesenteric ischemia.3 New-onset renovascular hypertension has been noted in 30–60% of patients. Laboratory findings may reveal acute kidney injury in 40–70% of patients. Elevated inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, have been found in 50% to over 80% of cases.1,3 ANA are found in 60% of cases. Serum IL‑6 may also be elevated, reflecting an acute phase response; its correlation with disease activity or prognosis is unexplored.

In patients who present with acute kidney injury from obstruction, the diagnosis may be delayed due to lack of significant hydronephrosis on imaging, as demonstrated in this case. Compression of the kidneys, aorta and renal arteries by inflammatory and fibrotic tissue leads to decreased renal perfusion and could cause hydroureteronephrosis.3 In patients with RPF, the degree of rise in serum creatinine is often out of proportion to the degree of hydronephrosis.

The diagnosis is made via imaging studies, such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. Retroperitoneal biopsy is only indicated in cases with atypical localization or with clinical findings suggestive for an alternative diagnosis.

Management

Management involves pharmacological as well as surgical approaches. The goal of idiopathic RPF treatment is to relieve ureteral obstruction via nephrostomy for patients with obstructive uropathy, followed by anti-fibrotic therapy to achieve disease regression.1 The cornerstone of medical therapy is corticosteroids, which suppress the synthesis of the cytokines involved in the fibroinflammatory response.9 Radiographic improvement is observed after about a week of treatment. Evaluation is recommended a month later to assess for disease response.9

Tamoxifen is commonly used as an alternative therapy if corticosteroids are contraindicated. In one small retrospective study, corticosteroids were found to be superior to tamoxifen for ameliorating symptoms, but patients who responded to tamoxifen had a lower chance of recurrence than those treated with corticosteroids.10

If remission is obtained, prednisone can be tapered to 5–10 mg/day and then maintained for an additional six to nine months.9 Studies are still ongoing regarding the use of biologics, such as rituximab and infliximab. Rituximab is now a standard therapy for the treatment of IgG4-RD.11 Other agents that can be used to induce remission include cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil and azathioprine.12

Table 1: Laboratory Test Results

| Laboratory | Patient | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|

| IgG | 1,214 mg/dL | 700–1,600 mg/dL |

| IgG1 | 629 mg/dL | 240–1,118 mg/dL |

| IgG2 | 504 mg/dL | 124–549 mg/dL |

| IgG3 | 87 mg/dL | 21–134 mg/dL |

| IgG4 | 60 mg/dL | 1–123 mg/dL |

| IgA | 157 mg/dL | 68–408 mg/dL |

| IgM | 109 mg/dL | 35–264 mg/dL |

| Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) screen immunofluorescence assay | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) IgG | <1:20 | <1:20 |

| Ganglioside (GM1) IgG | 4 IV | 0–50 IV |

| Ganglioside (GM1) IgM | 5 IV | 0–50 IV |

| Complement C3 | 144 mg/dL | 90–180 mg/dL |

| Complement C4 | 40 mg/dL | 10–40 mg/dL |

| Antistreptolysin screen | <55 IU/mL | 0–330 IU/mL |

| Serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and immunofixation (IFE) | Slight restriction of protein migration in the gamma region. Normal IFE pattern, no monoclonal proteins. | |

| Free κ light chains | 7.64 mg/dL | 0.33–1.94 mg/dL |

| Free λ light chains | 2.65 mg/dL | 0.57–2.63 mg/dL |

| Free κ/λ light chain ratio | 2.88 | 0.26–1.65 |

No standard criteria exist for the classification of idiopathic RPF, and specific diagnostic biomarkers are not available. The lack of significant hydronephrosis in obstructive nephropathy can be misleading and may delay the pursuit of additional investigations. The one-week course of prednisone this patient received for Bell’s palsy might have contributed to further delays in establishing her diagnosis of RPF.

Remission rates following treatment with corticosteroids vary from 75% to 95%; however, idiopathic RPF is a chronic relapsing disorder and even after successful treatment, the relapse rate may be as high as 72%.9 This warrants close monitoring and follow up over a long period of time after the initial presentation.

In Sum

Although rare, RPF should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with acute kidney injury secondary to obstructive uropathy with periaortic masses seen on imaging. Secondary causes should be excluded. The diagnosis of RPF can be made radiologically, without need for a biopsy.

Despite its chronic relapsing course, idiopathic RPF has good renal outcomes and progression to end-stage renal disease is rare with prompt treatment.

Roshniben Patel, MD, is a hospitalist at Ascension Saint Agnes Hospital, Baltimore.

Roshniben Patel, MD, is a hospitalist at Ascension Saint Agnes Hospital, Baltimore.

Simon Go, MD, is a chief resident in internal medicine at Ascension Saint Agnes Hospital, Baltimore.

Simon Go, MD, is a chief resident in internal medicine at Ascension Saint Agnes Hospital, Baltimore.

Akhila Mohan, MD, is a third-year resident in internal medicine at Ascension Saint Agnes Hospital, Baltimore.

Akhila Mohan, MD, is a third-year resident in internal medicine at Ascension Saint Agnes Hospital, Baltimore.

Maria Pardi, MD, is the associate program director of, and an academic hospitalist in, the internal medicine residency program at Ascension Saint Agnes Hospital, Baltimore.

Maria Pardi, MD, is the associate program director of, and an academic hospitalist in, the internal medicine residency program at Ascension Saint Agnes Hospital, Baltimore.

References

- Adnan S, Bouraoui A, Mehta S, et al. Retroperitoneal fibrosis; A single-centre case experience with literature review. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2018 Dec;3(1):rky050.

- Kermani TA, Crowson CS, Achenbach SJ, Luthra HS. Idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis: A retrospective review of clinical presentation, treatment, and outcomes. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011 Apr;86(4):297–303.

- Nguyen TV, Bader NM, Sidhu H, et al. Acute kidney failure in a young African American male. Case Rep Nephrol. 2019 Feb 17;2019:2591560.

- van Bommel EFH, Jansen I, Hendriksz TR, Aarnoudse ALHJ. Idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis: Prospective evaluation of incidence and clinicoradiologic presentation. Medicine (Baltimore). 2009 Jul;88(4):193–201.

- Maritati F, Rocco R, Accorsi Buttini E, et al. Clinical and prognostic significance of serum IgG4 in chronic periaortitis. An analysis of 113 patients. Front Immunol. 2019 Apr 4;10:693.

- Pischke S, Peron JM, von Wulffen M, et al. Chronic hepatitis E in rheumatology and internal medicine patients: A retrospective multicenter European cohort study. Viruses. 2019 Feb 22;11(2):186.

- Goldoni M, Bonini S, Urban ML, et al. Asbestos and smoking as risk factors for idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis: A case-control study. Ann Intern Med. 2014 Aug 5;161(3):181–188.

- Vaglio A, Catanoso MG, Spaggiari L, et al. Interleukin-6 as an inflammatory mediator and target of therapy in chronic periaortitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Sep;65(9):2469–2475.

- Cervera-Bonilla S, Garcia Mora M, Rodriguez Ossa P, et al. Medical challenge posed by retroperitoneal fibrosis: Case reports and literature review. Cureus. 2020 Jan 10;12(1):e6624.

- van der Bilt FE, Hendriksz TR, van der Meijden WA, et al. Outcome in patients with idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis treated with corticosteroid or tamoxifen monotherapy. Clin Kidney J. 2016 Apr;9(2):184–191.

- Khosroshahi A, Carruthers MN, Stone JH, et al. Rethinking Ormond’s disease: “Idiopathic” retroperitoneal fibrosis in the era of IgG4-related disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 2013 Mar;92(2):82–91.

- Warnatz K, Keskin AG, Uhl M, et al. Immunosuppressive treatment of chronic periaortitis: A retrospective study of 20 patients with chronic periaortitis and a review of the literature. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005 Jun;64(6):828–833.