Brandon Crawford / shutterstock.com

Cannabis arteritis mirrors thromboangiitis obliterans in its clinical and arteriographic presentation, but its relevant exposure is cannabis rather than tobacco.1 Whether cannabis arteritis is a subset of thromboangiitis obliterans or a unique pathologic entity is debatable.

Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, the primary psychoactive component of cannabis, is a peripheral vasoconstrictor.2 This offers mechanistic insight into how cannabis may cause the distal extremity ischemia characteristic of thromboangiitis obliterans. However, with rare exceptions, at least some tobacco use—concomitant with cannabis use—is reported in cases of cannabis arteritis.3,4

In the U.S., cannabis users infrequently mix loose tobacco with cannabis in a joint (i.e., cannabis rolled in cigarette paper) or pipe, as is typical in other countries.5 Yet almost two-thirds of cannabis users in the U.S. co-administer cannabis and tobacco at least occasionally as a blunt.5

Blunts are cigars or cigarillos that are hollowed out and filled with cannabis. A substantial minority of blunt smokers don’t consider themselves cigar or tobacco users.6 This has significant implications for obtaining the necessary social history in patients with a clinical presentation compatible with cannabis arteritis to reach the appropriate diagnosis, as demonstrated in this case.

Case Presentation

A 61-year-old man presented with a three-day history of diffuse swelling and pain in his right second finger. He had a three-month history of Raynaud’s phenomenon of the digits in both hands and a two-month history of progressively worsening, painful ulcerations of several distal fingertips. He had no inflammatory joint pain or swelling and no extremity numbness. He did not have fevers, weight loss, lymphadenopathy, dyspepsia, rashes or cutaneous nodules. He reported many months of dyspnea on exertion, and non-exertional, non-pleuritic substernal chest pain.

Whether cannabis arteritis is a subset of thromboangiitis obliterans or a unique pathologic entity is debatable.

His past medical history included hypertension and untreated hepatitis C. He had no known personal history of arterial or venous thrombosis. He was not taking any prescription medications, over-the-counter medications or supplements.

He smoked cannabis 8 to 10 times each week. He denied past or current tobacco use. He explicitly, and on multiple occasions, denied past or current smoking of cigarettes, cigars or pipes. He did not use any other drugs. He had no family history of autoimmune or metabolic diseases. He had never worked in an industrial factory.

Physical exam showed digital clubbing, with distal tuft swelling and tenderness of all distal fingertips. Dry ulcerations with a honey-colored crust were present on multiple fingertips, including the right second digit. This finger was diffusely swollen and tender. He could not flex the right second finger at the distal and proximal interphalangeal joints actively or passively due to severe pain. No sclerodactyly was present. The right third toe distal tuft was swollen, with a digital pit.

Figure 1. Acro-osteolysis with resorptive changes of the tufts of the distal phalanges of (A) the left first, second and third digits, and (B) the right second and third digits.

No joint swelling or tendon rubs were present. No rashes or skin tightening at any other sites was seen. His anterior chest was sun damaged, with occasional telangiectasia. No other telangiectasia at any other location, including the oral mucosa or palms, was noted. The neurologic, cardiovascular, pulmonary and the remainder of the musculoskeletal examinations were unrevealing.

X-rays revealed acro-osteolysis of the distal phalanges of the affected fingers (see Figure 1).

The patient was started on oral vasodilators, nifedipine and sildenafil for the digital ulcerations. Intravenous antibiotics were also initiated for a superimposed cellulitis of the right second finger.

An orthopedic surgeon did not recommend surgical intervention on the right second digit for complicated soft tissue infection.

Arterial ultrasound showed no occlusive thrombus or stenosis of involved extremities. Transthoracic echocardiography excluded an intracardiac thrombus. The patient had a normal complete blood count, basic metabolic panel and coagulation profile. The hepatic function panel showed mild transaminase elevation (see Table 1). Laboratory testing, together with the history and exam, reasonably excluded autoimmune disease, hypercoagulable state and diabetes mellitus (see Table 1).

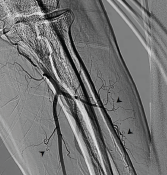

Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen and pelvis showed no evidence of vasculitis or pulmonary parenchymal disease, but atherosclerosis of the superior mesenteric and coronary arteries was seen. An invasive angiogram of both upper arms showed widely patent bilateral large vessels with severely diminished flow into the radial and ulnar arteries distally, with numerous corkscrew collateral arteries in the forearms (see Figure 2).

Table 1: Selected Laboratory Testing

| Laboratory test | Patient result | Normal values |

|---|---|---|

| Serum glucose (fasting) | 87 mg/dL | 74–106 mg/dL |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 44 U/L | 11–35 U/L |

| Alanine transaminase | 57 U/L | 10–49 U/L |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 32 mm/hr | 0–26 mm/hr |

| C-reactive protein | 2.77 mg/dL | 0.0–0.5 mg/dL |

| Rheumatoid factor | 20.3 IU/mL | 0–14 IU/mL |

| C3 | 138 mg/dL | 90–170 mg/dL |

| C4 | 41.6 mg/dL | 19–52 mg/dL |

| HIV screen1 | Nonreactive | Nonreactive |

| HBsAg | Nonreactive | Nonreactive |

| HBsAb | Nonreactive | Nonreactive |

| Hepatitis C antibody | Reactive | Nonreactive |

| Hepatitis C RNA VL | 264,657 IU/mL | ≤25 IU/mL |

| SARS-CoV-2 PCR | Negative | Negative |

| Thyroid stimulating hormone | 2.70 mcIU/mL | 0.4–4.7 mcIU/mL |

| Calcium (serum) | 9.3 mg/dL | 8.7–10.4 mg/dL |

| Parathyroid hormone | 32.6 pg/mL | 11.1–79.5 pg/mL |

| Anti-nuclear antibody | 1:80, nucleolar pattern | ≤1:40 |

| U1-RNP antibody | <0.2 U | <1.0 U |

| Smith antibody | <0.2 U | <1.0 U |

| dsDNA antibody | <12.3 IU/mL | <30.0 IU/mL |

| Scl-70 antibody | <0.2 U | <1.0 U |

| Centromere antibody | <0.2 U | <1.0 U |

| ANCA proteinase 3 | <0.2 U | <0.4 U |

| ANCA myeloperoxidase | <0.2 U | <0.4 U |

| β-2-glycoprotein-1 IgG | <9.4 U/mL | <15.0 U/mL |

| β-2-glycoprotein-1 IgM | <9.4 U/mL | <15.0 U/mL |

| Cardiolipin IgG | <9.4 MPL | < 15.0 MPL |

| Cardiolipin IgM2 | <9.4 MPL | <15.0 MPL |

| Cryoglobulins | Negative | Negative |

| SPEP/SIFE | No monoclonal Ig | No monoclonal Ig |

Key: HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus; HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen; HBsAb: Hepatitis B surface antibody; RNA VL: Ribonucleic acid viral load; SARS-CoV-2 PCR: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 polymerase chain reaction; U1-RNP: U1 ribonucleoprotein; dsDNA: Double stranded deoxyribonucleic acid; ANCA: Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; Ig: Immunoglobulin; SPEP/SIFE: Serum protein electrophoresis/serum immunofixation

Notes

1 HIV antigen/antibody combination assay simultaneously detected HIV-1 p24 antigen, antibodies to HIV-1 (group M and O)—IgG and IgM, and antibodies to HIV-2—IgG and IgM.

2 Lupus anticoagulant was not obtained because the patient was receiving low-molecular weight heparin for deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis.

At this juncture, we explicitly questioned the patient on his mode of cannabis administration and discovered he was a daily blunt smoker.

Figure 2. Invasive angiogram of left brachial artery terminating into the radial and ulnar arteries. Note the multiple corkscrew collateral vessels off the radial and ulnar arteries (arrowheads).

The patient had decreased hand pain with nifedipine and sildenafil. After several days, his right second digit began spontaneously draining serosanguinous fluid, which was cultured and grew Klebsiella oxytoca. The patient’s antibiotics were tailored to an oral regimen based on antimicrobial susceptibilities, and he was discharged. After one month, in outpatient follow-up, the patient’s digital ulcerations had improved with oral vasodilators. Despite counseling, he continued to regularly smoke blunts filled with cannabis.

Discussion

In this case, we have objective evidence of distal-extremity ischemia in the form of multiple subacute digital ulcerations and underlying acro-osteolysis on X-ray in the setting of regular cannabis exposure. This constellation of features raises the possibility of cannabis arteritis. However, cannabis arteritis is a diagnosis of exclusion.7 After thorough assessment, no evidence supported autoimmune disease or hypercoagulable state as the cause of his presentation.

This patient did have increased inflammatory markers, yet these relatively mild elevations could reasonably be attributed to his superimposed right second digit cellulitis. The patient’s laboratory evaluation was remarkable for mild transaminase elevation, positive hepatitis C antibody and slightly increased rheumatoid factor in the setting of known, untreated hepatitis C. This raised the question of cryoglobulinemic vasculitis. However, the patient lacked constitutional symptoms or other end-organ manifestations of a vasculitis aside from digital ischemia. Further, his complements were normal and cryoglobulins were not detected. Therefore, a cryoglobulinemic-associated vasculitis was unlikely.

Despite a low-titer positive anti-nuclear antibody, extractable nuclear antigens and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were not detected. Taken together with the absence of other symptoms or physical exam findings to suggest connective tissue disease, autoimmune disease was reasonably unlikely in this case.

A hypercoagulable state was likewise unlikely. The patient had no history of venous or arterial thrombosis, and antiphospholipid antibodies were not detected. A proximal source of emboli was not found on either transthoracic echocardiography or invasive angiogram, where vessels proximal to the elbow were largely patent on both arms. No significant proximal atherosclerosis was seen on invasive angiogram. Further, his invasive angiogram was highly consistent with cannabis arteritis given the diminished distal flow and numerous corkscrew collateral arteries.1,7

The patient did not have diabetes mellitus given his normal fasting serum glucose levels; diffuse atherosclerotic disease in the setting of diabetes mellitus as a mimic of the invasive angiogram findings was, therefore, unlikely. Despite the patient’s age of 61, older than the mean age at presentation for cannabis arteritis in the literature, cannabis arteritis was the most appropriate diagnosis in this case.

To our knowledge, cannabis arteritis has only rarely been reported in the complete absence of any concomitant tobacco use.3,4 Therefore, in our case, the lack of any history of associated tobacco exposure was befuddling until we discovered the patient was not just a daily cannabis user, but a daily blunt user. Although the tobacco filler in a cigar or cigarillo is removed and replaced with cannabis to make a blunt, the cigar or cigarillo wrapper is itself made of tobacco.8

Mass spectrometry shows that among commonly used cigar brands for making blunts, cigar wrappers have between 8% and 40% of the nicotine content of a standard cigarette.8 Our patient’s chosen vehicle of cannabis administration itself is made of tobacco. This case highlights the importance of explicitly asking cannabis users about their cannabis administration method to ascertain if tobacco and cannabis co-use is present via smoking blunts.

Further, the method may have implications in the prognosis of cannabis arteritis. Poor prognosis in cannabis arteritis is directly linked to continued cannabis consumption.4 Blunt smoking is associated with increased cannabis dependence, which may impede cannabis discontinuation in blunt users with cannabis arteritis.5,9

Rachel E. Elam, MD, ScM, is an assistant professor of medicine and an adult rheumatologist at Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University and is in her first year of practice.

Rachel E. Elam, MD, ScM, is an assistant professor of medicine and an adult rheumatologist at Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University and is in her first year of practice.

Vishal Arora, MD, is an interventional cardiologist and professor of medicine at Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, practicing for 12 years. He serves as program director of the Interventional Cardiology Fellowship Program.

Vishal Arora, MD, is an interventional cardiologist and professor of medicine at Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, practicing for 12 years. He serves as program director of the Interventional Cardiology Fellowship Program.

Alyce M. Oliver, PhD, MD, is an adult rheumatologist, professor of medicine, Joseph P. Bailey, MD, Chair in Rheumatology, Division of Rheumatology and the director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program for the Medical College of Georgia (MCG) at Augusta University. She was formerly the MCG Rheumatology Fellowship program director.

Alyce M. Oliver, PhD, MD, is an adult rheumatologist, professor of medicine, Joseph P. Bailey, MD, Chair in Rheumatology, Division of Rheumatology and the director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program for the Medical College of Georgia (MCG) at Augusta University. She was formerly the MCG Rheumatology Fellowship program director.

References

- Olin JW, Shih A. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006 Jan;18(1):18–24.

- Adams MD, Earnhardt JT, Dewey WL, Harris LS. Vasoconstrictor actions of delta8- and delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol in the rate. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1976 Mar;196(3):649–656.

- Peyrot I, Garsaud A-M, Saint-Cyr I, et al. Cannabis arteritis: A new case report and a review of literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007 Mar;21(3):388–391.

- Cottencin O, Karila L, Lambert M, et al. Cannabis arteritis: Review of the literature. J Addict Med. 2010 Dec;4(4):191–196.

- Fairman BJ. Cannabis problem experiences among users of the tobacco-cannabis combination known as blunts. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015 May 1;150:77–84.

- Delnevo CD, Bover-Manderski MT, Hrywna M. Cigar, marijuana, and blunt use among US adolescents: Are we accurately estimated the prevalence of cigar smoking among youth? Prev Med. 2011 Jun;52(6):475–476.

- Olin JW. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). N Engl J Med. 2000 Sep 21;343(12):864–869.

- Peters EN, Schauer GL, Rosenberry ZR, Pickworth WB. Does cannabis “blunt” smoking contribute to nicotine exposure?: Preliminary product testing of nicotine content in wrappers of cigars commonly used for blunt smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016 Nov 1;168:119–122.

- Timberlake DS. A comparison of drug use and dependence between blunt smokers and other cannabis users. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44(3):401–415.