Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic autoimmune inflammatory disease. Although RA develops its central pathology within the synovium of diarthrodial joints, many non-articular organs can be involved, particularly in patients with severe joint disease.1 Although most patients are asymptomatic, cardiac involvement is relatively common and includes rheumatic heart nodules, pericarditis (30–50%), pericardial effusion and conduction abnormalities.2,3 Cardiac tamponade due to rheumatoid pericarditis is considered rare and may present a diagnostic challenge.4

This article describes a case of 64-year-old man with a three-year history of rheumatoid arthritis who presented with rheumatoid pericarditis and cardiac tamponade physiology.

The Case

Mr. M is a 64-year-old man from El Salvador with a past medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension and seropositive RA, who presented to an outside hospital with acute-onset, left-sided chest pain. The chest pain was constant, progressively worsening, exacerbated with deep inspiration and relieved by lying flat and on his left side. He was noted to be tachycardic to 130–140s and his systolic blood pressure was in the 90s; an electrocardiogram showed ST elevation at I, AVL and V5–6. He was initially given thrombolytic therapy due to concern for acute coronary syndrome and transferred to our hospital for further management.

The patient was diagnosed with RA in 2015 when he presented with polyarticular joint pain. He was subsequently started on methotrexate, but he did not tolerate the medication well due to nausea and gastrointestinal discomfort. Subcutaneous adalimumab, 40 mg every two weeks, was added a month later; however, he stopped taking both medications a few weeks later because he felt “unwell.”

Upon arrival at our hospital, Mr. M underwent a left heart catheterization that revealed normal coronary arteries. Physical examination revealed a pulse of 134, respiration of 21, blood pressure of 108/75 and oxygen saturation of 93% on room air. No jugular venous distention was appreciated, and no friction rub was heard; however, muffled heart sounds and decreased breath sounds were noted. Synovitis was present in his right wrist, right second and third metacarpophalangeal joints, and left second metacarpophalangeal joints.

Laboratory data included elevated white blood cells at 20×103/mm3 (87% neutrophils, 7% lymphocytes and 6% monocytes), normocytic anemia (hemoglobin: 11.4 g/dL) and mild thrombocytosis (a platelet count of 479×103/mm3). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was normal at 36, but the C-reactive protein was >190 mg/L. Rheumatoid factor was present at an elevated titer of 536 IU/mL and anti-citrullinated cyclic peptide antibodies were positive at 181 units. The patient tested negative for anti-nuclear antibodies. Human immunodeficiency virus was not detected, and the T-SPOT tuberculosis test was negative.

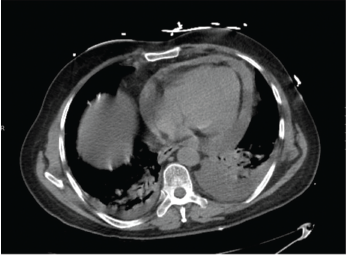

A chest X-ray showed moderate cardiomegaly and a tortuous aorta (see Figure 1, top right). A computed tomography angiogram revealed a moderate-size complex pericardial effusion (see Figure 2, bottom right). An echocardiogram showed moderate pericardial effusion with signs of tamponade.

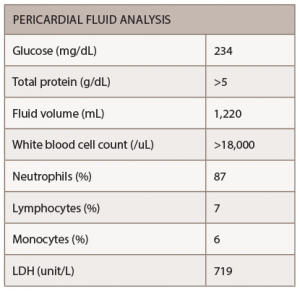

The patient underwent pericardiocentesis with the removal of 380 cc of bloody fluid. The findings of pericardial fluid are listed below (see Table 1).

The pericardial fluid showed no growth of bacterial or fungal cultures, and no acid-fast bacilli were seen, making mycobacterium tuberculosis unlikely. No evidence of malignant cells was found in the pericardial fluid. Colchicine with an anti-inflammatory medication were administered for the treatment of pericarditis.

Two days after the pericardiocentesis, the patient was transferred to the cardiac floor from the medical intensive care unit in stable condition. A repeat echocardiogram showed a left ventricle normal in size, with normal wall thickness and preserved systolic function, as well as minimal residual pericardial effusion.

Methotrexate was restarted after the infectious workup remained negative. The patient was discharged in stable condition, with no recurrence of symptoms on 0.6 mg of colchicine twice daily, 600 mg of ibuprofen three times daily and 20 mg of methotrexate weekly. He had a follow-up scheduled in two weeks with his rheumatologist when he would likely restart adalimumab.

Discussion

Pericardial involvement has been detected in a high percentage of RA patients in necropsy and echocardiographic studies (11–50%), but neither cardiac tamponade nor constrictive pericarditis is considered a common complication of the disease.5,2

Pericardial tamponade due to rheumatoid pericarditis can be a life-threatening complication.6 In 1990, Escalante et al. described 960 patients with RA who were followed over 11 years, and only five manifest cardiac compression.6 The male-to-female ratio of RA patients with tamponade (11:8) also differs from the normal RA population gender distribution, which typically trends toward women.6

Figure 1: A chest X-ray demonstrated moderate cardiomegaly with tortuous aorta.

Figure 2: A computed tomography angiogram of the chest showed a moderate-sized complex pericardial effusion.

Cardiac compressions in rheumatoid pericarditis have also occurred in patients mostly older than 60 years with long-standing disease, according to most literature reported to date, including Nomeir et al. and Escalante et al.3,6 Symptomatic pericarditis often takes place in association with other extra-articular manifestations; rheumatoid factor is positive in 95% of the cases, and subcutaneous nodules are found in 35% of the patients.7

Diagnosis of Cardiac Tamponade

The diagnosis of cardiac tamponade can be made clinically by the finding of raised jugular venous pressure, distant heart sounds, hepatomegaly, ankle edema and pulsus paradoxus, and is substantiated by cardiac screening and echocardiography. In a review of 48 patients with RA, the authors described jugular vein distension in 60% and edema in 47%, although pulsus paradoxus or Kussmaul’s sign were uncommon.5

In the case of Mr. M, a muffled heart sound presented with no other physical examination finding of tamponade. The important diagnostic tool is aspiration of pericardial fluid. In the majority of reported cases the most frequent character of the fluid is hemorrhagic or serosanguinous. The fluid has the characteristic of exudate with high protein and lactate dehydrogenase.8 The sugar content of the fluid is either very low or absent.9 Cellular content is variable, but tends to be higher than 2,000.

In this case, pericardial fluid glucose was 234 mg/dL, but the protein was more than 5 g/dL. Most importantly, the cell count of more than 18,000 with the negative infectious and malignancy workup makes RA the most likely cause.

The infrequency of compressive pericardial diseases in RA limits the feasibility of studies to establish the effectiveness of any particular treatment strategy. Previous reports have demonstrated that treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressive drugs may be appropriate for RA-associated pericarditis.10

Systemic corticosteroids are often ineffective for the treatment of cardiac compression caused by rheumatoid pericarditis. Instead, percutaneous catheter drainage and surgical tube drainage are warranted.10 Rheumatoid pericardial effusions have responded to more intensive immunosuppression; however, some controversy exists on the effectiveness of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors on extra-articular manifestation.11

This is a rare complication that has historically occurred in patients with seropositive active rheumatoid arthritis, but its occurrence in patients with quiescent joint disease while on tumor necrosis factor inhibitors has been reported.11

Few studies have been conducted on RA as a cause for cardiac tamponade. No evidence-based therapeutic guidelines for rheumatoid pericarditis have been established yet. Further investigations are needed to make proper treatment recommendations.

Sirajum Munira, MD, is a third-year resident in the internal medicine residency program at Saint Agnes Hospital, Baltimore.

Sirajum Munira, MD, is a third-year resident in the internal medicine residency program at Saint Agnes Hospital, Baltimore.

Mamta Sherchan, MD, is a first-year fellow in the rheumatology department of MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington, D.C. She completed her residency in internal medicine at Saint Agnes Hospital, Baltimore.

Mamta Sherchan, MD, is a first-year fellow in the rheumatology department of MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington, D.C. She completed her residency in internal medicine at Saint Agnes Hospital, Baltimore.

Christopher Collins, MD, FACR, is an attending rheumatologist and associate program director of the Rheumatology Division, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, and an assistant professor of medicine, Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, D.C.

Christopher Collins, MD, FACR, is an attending rheumatologist and associate program director of the Rheumatology Division, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, and an assistant professor of medicine, Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, D.C.

References

- Davis JM 3rd, Matteson EL, et al. My treatment approach to rheumatoid arthritis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012 Jul;87(7):659–673.

- Bonfiglio T, Atwater EC. Heart disease in patients with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis; a controlled autopsy study and review. Arch Intern Med. 1969 Dec;124(6):714–719.

- Nomeir AM, Turner R, Watts E, et al. Cardiac involvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Intern Med. 1973 Dec;79:800–806.

- Hara KS, Ballard DJ, Ilstrup DM, et al. Rheumatoid pericarditis: Clinical features and survival. Medicine (Baltimore). 1990 Mar:69(2):81–91.

- Thadani U, Iveson JM, Wright V. Cardiac tamponade, constrictive pericarditis and pericardial resection in rheumatoid arthritis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1975 May;54(3):261–270.

- Escalante A, Kaufman RL, Quismorio FP Jr., et al. Cardiac compression in rheumatoid pericarditis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1990 Dec;20(3):148–163.

- Franco, AE, Levine, HD, Hall, AP. Rheumatoid pericarditis. Report of 17 cases diagnosed clinically. Ann Intern Med. 1972 Dec;77(6):837–844.

- Richards AJ, Koehler BE, Broder I, et al. Rheumatoid pericarditis: Comparison of immunologic characteristics of pericardial fluid, synovial fluid, and serum. J Rheumatol. 1976 Sep;3(3):275–282.

- Latham BA. Pericarditis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1966 May;25(3):235–241.

- Imadachi H, Imadachi S, Koga T, et al. Successful treatment of refractory cardiac tamponade due to rheumatoid arthritis using pericardial drainage. Rheumatol Int. 2010 Jun;30(8):1103–1106.

- Soh MC, Hart HH, Corkill M. Pericardial effusions with tamponade and visceral constriction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis on tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-inhibitor therapy. Int J Rheum Dis. 2009 Apr;12(1):74–77.