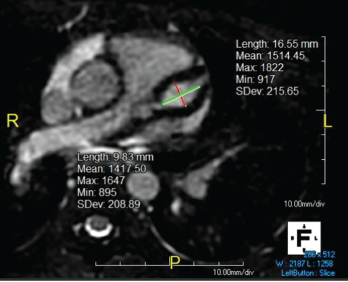

Figure 1. Giant LAD fusiform aneurysm measuring 9.8 mm in diameter (z-score = 19) and extending approximately 17 mm.

In September 2019, a previously healthy, 9-year-old white girl presented to the emergency department following two months of sinusitis and unexplained fever responsive to ibuprofen. She presented with anorexia; a 9 lb. weight loss; intermittent, nonbilious, nonbloody emesis; and occasional epistaxis with digital manipulation of the nose.

Six weeks prior to admission, she had presented to the emergency department with fever and rhinorrhea unresolved by amoxicillin. An evaluation revealed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 58 mm/hr (reference range [RR] 0–20 mm/hr), a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 22 mg/L (RR: 0–9 mg/L), a white blood cell (WBC) count of 17.6 cells/μL (RR: 5.4–9.7 cells/μL) and a hematocrit level of 41% (RR: 35–43%). A chest radiograph was unrevealing, and the urinalysis was normal, demonstrating a baseline creatinine (Cr) level of 0.4 mg/dL (RR: 0.31–0.61 mg/dl). She tested positive for enterovirus and was sent home with conservative management.

Two weeks prior to admission, the patient had been seen by an infectious disease specialist due to persistent fevers. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), uric acid, cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus titers were performed and found to be normal. She was noted to be incompletely vaccinated.

On admission, a physical examination revealed pale, friable nasal mucosa; a subtle transverse nasal crease; livedo reticularis on her hands and feet; and pseudofolliculitis in the lower extremities. She had no maxillary tenderness, and pulmonary and cardiac exams were unremarkable. Her vital signs were within normal limits.

Laboratory testing on admission showed an ESR of 10 mm/hr, a CRP of 16.3 mg/L, a WBC of 22.0 cells/μL, hematocrit of 26%, platelets of 574 K/uL (RR: 150–400 K/uL), Cr of 1.3 mg/dL and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) of 944 U/L (RR: 420–750 U/L). Urinalysis revealed 10–25 RBC/HPF (normal: <5) and 5–10 WBCs/HPF (normal: <5/HPF), but was negative for protein and leukocyte esterase.

The patient was admitted for pre-renal azotemia, leukocytosis and fever of unknown origin, and intravenous ceftriaxone and fluids were administered.

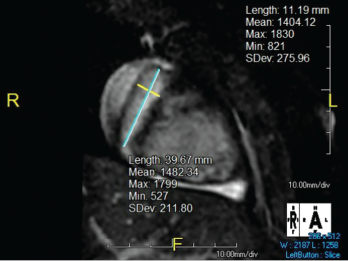

As part of the evaluation for a fever of unknown origin, an echocardiogram was performed and revealed severe bilateral fusiform aneurysms 6–7 mm in diameter in both coronary arteries, as well as mild tricuspid, mitral and aortic valve regurgitation. An electrocardiogram showed 1 mm ST depressions in the lateral leads and QT prolongation to 541 ms. Troponin was initially 0.09 ng/mL (RR: 0–0.08 ng/mL), but normalized at 12 hours.

An abdominal ultrasound showed loss of corticomedullary differentiation in both kidneys. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) revealed a wedge-shaped region of enhancement suspicious for subacute to chronic renal infarct. MRAs of the chest, abdomen and head showed no other aneurysms.

Her hematocrit dropped to 24%. The patient’s valvular involvement was atypical for Kawasaki disease, and additional laboratory tests demonstrated proteinase-3 IgG >8.0 U (<0.4 U), C-ANCA (anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies) 1:256 (negative), anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) 1:320 (normal: <1:40) with a speckled pattern, and normal complement levels. It was not until 10 days later that her urinalysis indicated proteinuria and a urine protein to creatinine ratio of 3.4.

Diagnosis & Treatment

Figure 2. The right coronary artery sustained a giant fusiform aneurysm 11 mm in diameter (z-score = 20) and 40 mm in length.

The patient was diagnosed with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and started on 1,000 mg of pulse dose intravenous methylprednisolone daily for three days and 81 mg daily of aspirin.

Sinus computerized tomography (CT) showed mucosal thickening and “bubbly” fluid in the sphenoid sinuses. A chest CT showed pleural effusions and potential upper lung nodules measuring 5 mm. A percutaneous biopsy of the left kidney revealed severe necrotizing crescentic pauci-immune glomerulonephritis.

Overall, this patient demonstrated severe manifestations of GPA equating to a validated Pediatric Vasculitis Activity Score (PVAS) of 34.1 Note that the current PVAS does not include scoring criteria for coronary artery aneurysms.1

Because of the severity of the renal disease, the patient was treated with 1 mg/kg/day methylprednisolone, 15 mg/kg of intravenous cyclophosphamide every two weeks for two doses and 375 mg/m2/week of rituximab for four weeks, a combination regimen consistent with the RITUXVAS trial.2 After four doses of rituximab, the patient denied any symptoms beyond mild rhinorrhea, and her renal disease gradually resolved.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging was performed, revealing giant aneurysms (see Figure 1, and Figure 2). The patient was subsequently started on warfarin and aspirin; she continues to have no cardiac symptoms. Continued management with rituximab as maintenance therapy is consistent with the MAINRITSAN trial.3 As of December 2020, the patient had a persistent PVAS of 2, secondary to residual valvular heart disease.

Discussion

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis is a small-vessel vasculitis associated with ANCA and multi-organ involvement.4 Aside from Kawasaki disease and IgA vasculitis, the systemic vasculitides are rare in the pediatric population, at an incidence of 0.24 per 100,000 children annually.1,5 Consequently, the average delay from symptom onset to diagnosis is 2.1 months, with a hospitalization rate 1.3 times that of adults.4,6

GPA typically presents with involvement of the upper and lower respiratory tracts, as well as renal manifestations, most commonly pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis.5,7

The clinician who suspects or diagnoses an ANCA-associated vasculitis in a pediatric patient should consider coronary artery aneurysms as a possible & dangerous sequela.

Cardiac involvement in GPA is typically limited to venous thrombosis, as reported in three of 183 patients in the ARChiVe study.4 One reported case of coronary artery aneurysms in GPA, published in December 2010, involved a 25-year-old man who subsequently experienced an expansive anterior myocardial infarction and ventricular tachycardia necessitating electrical cardioversion.8 Cardiac involvement in GPA can also have confounding presentations. Varnier et al. described a 16-year-old boy with a tricuspid vegetation masquerading as infective endocarditis despite negative cultures and a positive PR3-ANCA.9

Our patient’s unique cardiac manifestations brought to the authors’ attention three significant considerations:

- ANCA-associated vasculitis should be considered in children with coronary artery aneurysms, especially if their presentation is atypical for Kawasaki disease;

- The clinician who suspects or diagnoses an ANCA-associated vasculitis in a pediatric patient should consider coronary artery aneurysms as a possible and dangerous sequela; and

- Coronary artery aneurysms should be included in the PVAS scoring criteria.

Tryphina Adel Mikhail has a B.S. in Biomedical Sciences and is a fourth-year medical student at the University of Central Florida College of Medicine, Orlando. She plans to pursue a career in pediatrics and medical education.

Tryphina Adel Mikhail has a B.S. in Biomedical Sciences and is a fourth-year medical student at the University of Central Florida College of Medicine, Orlando. She plans to pursue a career in pediatrics and medical education.

Mary Bratovich Toth, MD, is a professor of pediatrics at the University of Central Florida College of Medicine and the pediatric rheumatology division chief for Nemours Children’s Hospital, Orlando. She is faculty for the adult rheumatology fellowship at the University of Central Florida and active in CARRA (Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance).

Mary Bratovich Toth, MD, is a professor of pediatrics at the University of Central Florida College of Medicine and the pediatric rheumatology division chief for Nemours Children’s Hospital, Orlando. She is faculty for the adult rheumatology fellowship at the University of Central Florida and active in CARRA (Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance).

References

- Dolezalova P, Price-Kuehne FE, Özen S, et al. Disease activity assessment in childhood vasculitis: Development and preliminary validation of the Paediatric Vasculitis Activity Score (PVAS). Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Oct;

72(10):1628–1633. - Jones RB, Cohen Tervaert JW, Hauser T, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide in ANCA-associated renal vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul;363(3):211–220.

- 3Guillevin L, Pagnoux C, Karras A, et al. Rituximab versus azathioprine for maintenance in ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2014 Nov;371(19):1771–1780.

- Cabral DA, Canter DL, Muscal E, et al. Comparing presenting clinical features in 48 children with microscopic polyangiitis to 183 children who have granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s): An ARChiVe cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016 Oct;68(10):2514–2526.

- Iudici M, Quartier P, Terrier B, et al. Childhood-onset granulomatosis with polyangiitis and microscopic polyangiitis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016 Oct 22;11(1):141.

- Panupattanapong S, Stwalley DL, White AJ, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of granulomatosis with polyangiitis in pediatric and working‐age adult populations in the United States: Analysis of a large national claims database. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 Dec;70(12):2067–2076.

- Jariwala MP, Laxer RM. Primary vasculitis in childhood: GPA and MPA in childhood. Front Pediatr. 2018 Aug 16;6:226.

- Musuruana JL, Cavallasca JA, Berduc J, et al. Coronary artery aneurysms in Wegener’s granulomatosis. Joint Bone Spine. 2011 May;78(3):309–311.

- Varnier GC, Sebire N, Christov G, et al. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis mimicking infective endocarditis in an adolescent male. Clin Rheumatol. 2016 Sep;35(9):2369–2372.