Pachydermoperiostosis (PDP), also known as Touraine-Solente-Golé syndrome or primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy, is a rare syndrome that can be inherited as autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or sporadically. This progressive disease primarily affects males, who tend to have more severe features than females. PDP usually occurs during adolescence, often starting around puberty.1 The main clinical features are clubbing, pachydermia and hyperhidrosis. Fortunately, it is a self-limiting disease. However, it can be difficult to diagnose and treat. This report describes the current known pathogenesis of PDP and possible associated abnormalities that could explain potential gastrointestinal (GI) manifestations.

Pachydermoperiostosis (PDP), also known as Touraine-Solente-Golé syndrome or primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy, is a rare syndrome that can be inherited as autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or sporadically. This progressive disease primarily affects males, who tend to have more severe features than females. PDP usually occurs during adolescence, often starting around puberty.1 The main clinical features are clubbing, pachydermia and hyperhidrosis. Fortunately, it is a self-limiting disease. However, it can be difficult to diagnose and treat. This report describes the current known pathogenesis of PDP and possible associated abnormalities that could explain potential gastrointestinal (GI) manifestations.

Case Presentation

A 16-year-old young man presented with a history of protein-losing enteropathy, recurrent diarrhea secondary to Clostridioides difficile (C. diff) infections, iron deficiency and concern for eosinophilic esophagitis or Crohn’s disease. He had previously been healthy, with no pertinent family history, until he developed a gagging sensation at about 13 years old.

He was followed by gastroenterologists at multiple institutions who were concerned about the possibility of Crohn’s disease, but never received a confirmed diagnosis. He developed intermittent abdominal pain, as well as loose stools. An inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) serology panel was suggestive of Crohn’s disease. (Note: An ECM1 variant with single-nucleotide polymorphism was detected, but signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 [STAT3] variant were not detected, both of which would be unusual findings in an IBD panel; VEGF and inflammatory markers were elevated.)

Abdominal ultrasound showed a small focus of adherent sludge or a small polyp in the gallbladder, but was otherwise unrevealing.

Double-balloon enteroscopy with a capsule endoscopy was performed, which noted two proximal ileal strictures. A biopsy of the ulcerated stricture area showed mild, active ileitis with mixed inflammatory infiltrate, focal ulceration and reactive changes.

Repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy/colonoscopy showed mild inflammation of the distal colon and lymphoplasmacytosis. Fecal calprotectin fluctuated between abnormal, borderline and normal. Inflammatory markers were mildly abnormal, with the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) fluctuating between 29 and 53 mm/hr (reference range [RR]: <11 mm/hr) and C-reactive protein (CRP) between 1.0 and 4.7 mg/dL (RR: <1 mg/dL).

In the past, the patient had tested positive multiple times for stool α1-antitrypsin, which helped lead to a diagnosis of protein-losing enteropathy. He was initially treated with metronidazole, vancomycin and fidaxomicin due to multiple C. diff infections.

One-and-a-half years prior to this presentation, he had complained of knee and foot swelling. The pain and swelling worsened with activity, and he had daily morning stiffness for 10 minutes. He was evaluated by a cardiologist for foot edema, but had a normal echocardiogram. Ultrasound of his extremities ruled out deep vein thromboses. His symptoms progressed, and he developed hand swelling, with limited range of motion. Due to worsening symptoms, he was admitted for further evaluation and a rheumatologist was consulted.

During the rheumatologic consultation at this presentation, the patient had a striking physical appearance, with prominent forehead creases (see Figure 1). According to the patient, these had developed within the past year or two. He had multiple joint effusions in the wrists and knees (see Figure 2). He had limited

range of motion in his left shoulder, elbows, wrists, knees and ankles. His range of motion was also limited with reduced flexion of his metacarpophalangeal joints (MCP) and proximal interphalangeal joints (PIP) on both hands and thickened fingers. He had edema and tenderness of the midfoot, as well as tenderness of the Achilles tendon on palpation (see Figure 2). No clubbing was noted on the examination, but he did have cutis verticis gyrata (i.e., thickening of his scalp).

Laboratory tests at this time revealed low ferritin levels. Fecal occult blood and fecal calprotectin were abnormal. His CRP and ESR were elevated. His IgG level was mildly elevated, but he had normal IgA and IgM levels. HLA-B27, cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP), rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) tests were negative.

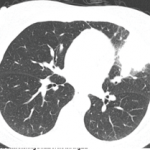

Magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) and X-ray of the sacroiliac (SI) joints were unremarkable. X-rays showed generalized osteopenia with periosteal reaction and sclerosis of both ulna (see Figure 3). He had small, suprapatellar effusions on both legs. Due to concern for both enthesitis-related juvenile idiopathic arthritis (ERA-JIA) and Crohn’s disease, he was started on 10 mg of oral methotrexate weekly and 40 mg of adalimumab via subcutaneous injection every two weeks.

He did not show much improvement on medication, and—given his striking physical examination, with forehead furrowing, and further literature searches—his case was reconsidered; his symptoms were found to be consistent with PDP.

Genetic testing was subsequently performed, revealing two heterozygous pathogenic variants in SLCO2A1.

Methotrexate was subsequently increased to 20 mg weekly, and he was switched from adalimumab to infliximab infusions due to his poor response and GI symptoms. Around the time his medications were changed, the patient started physical therapy, and dietary restrictions appropriate for patients with IBD were implemented. The patient responded to treatment, with improved knee effusions and pain. However, digit thickness continued to progress. Unfortunately, the patient developed antibodies to infliximab and the exclusionary diet was discontinued. Since then, his joint swelling and pachyderma have worsened.

Eventually, the patient was started on golimumab infusions at 100 mg every four weeks, along with subcutaneous 20 mg of methotrexate weekly. The patient experienced significant improvement in his arthritis. This improvement also coincided with utilization of a Crohn’s elimination diet, which further lowered his gastrointestinal inflammation.

As this is written, it has been more than two years since his presentation to the rheumatologist.

Discussion

The first reported case of PDP was in 1868.1 It most frequently occurs in males, and usually develops in the teenage years, presenting with clubbing, skin thickening and periostosis. The combination of thickened skin and bony enlargement can result in significant thickening of the extremities, which is often a very striking physical finding. The skin thickening can also be very prominent on the forehead and face.2 The digital clubbing, from some reports, occurs in about 89% of cases. There have also been reports of hypertrophy of the eyelids in 30–40% of patients and cutis verticis gyrata in 24% of patients. Cutis verticis gyrata is a thickening of the skin along the scalp that results in an appearance similar to the gyri of the brain.3 Ninety percent of patients tend to have seborrheic dermatitis. Other findings consist of acne, folliculitis, polyarthritis, palpebral ptosis, hyperhidrosis and acro-ostolysis of the long bones.1

Radiographs often reveal diffuse periostosis along the length of bones, including epiphyses in 80–97% of cases, and often with irregular contour.4 The diagnosis of PDP can be based on the presence of at least two of the four criteria set by Borochowitz et al.5:

- History of familial transmission,

- Pachyderma,

- Digital clubbing, and/or

- Skeletal manifestations, such as pain or signs of radiographic periostitis.

PDP has three clinical variants: complete, with pachyderma, clubbing and periostosis; incomplete, with isolated periostosis and limited skin changes; and forme fruste, presenting predominantly with pachyderma, with minimal periostosis.6

Due to the unusual presentation of these patients, many etiologies are often considered at onset, including multiple autoimmune and rheumatic conditions. PDP occurring along with other autoimmune conditions has been reported; one patient had concurrent PDP and limited scleroderma.7 PDP can be distinguished from scleroderma due to periosteal proliferation of the bones and hypertrophic skin changes.

Although the pathogenesis of PDP is still not clearly understood, studies have found genetic abnormalities, with pathogenic theories proposed. A study performed in 2005 reviewed pedigree data published on 68 families with 204 patients.8 The analysis showed evidence of an autosomal dominant mutation in 37 families and suggested the existence of an autosomal recessive form in the remaining families. Despite the incidence of PDP presenting mostly in young men, no X-linked pattern was noted. Theories suggest a potential relation to testosterone effects, such as promoting proliferation. The study did not include genetic testing, only pedigree evaluation.

The disease has been mapped to chromosome 4q33-q34 and mutations in 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (HPGD), which is the main enzyme for prostaglandin degradation.9,10 There is also a link to a genetic mutation in the SLCO2A1 gene, which disturbs prostaglandin metabolism via a deficient transmembrane prostaglandin transporter.11

Genetic mutations in HPGD and SLCO2A1 lead to increased levels of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), which appears to contribute to the pathogenesis of PDP.12,13 The severity of pachyderma and associated histological changes have been correlated with serum PGE2 levels and SLCO2A1 genotypes. PGE2 can mimic the activity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts, which may be responsible for the periosteal bone formation. Further, the prolonged local vasodilatory effects of PGE2 may explain digital clubbing.

PDP is self-limiting and usually stabilizes 5–20 years after onset.4 However, orthopedic disability can occur. The standard treatment includes non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for pain relief. Bisphosphonates, such as pamidronate, have been used to treat PDP due to their antiresorptive and osteoclast inhibitory properties.

Reports exist of multiple medications used being simultaneously: celecoxib and colchicine for articular abnormalities, folliculitis and pachyderma; pamidronate for rheumatologic manifestations, such as bone lesions; vagotomy of vagal nerve branches to improve joint pain/swelling; and isotretinoin for skin symptoms.2

PDP and IBD have occurred simultaneously, specifically in Crohn’s disease. As of 2018, four such case reports had been found. In one case, a patient with a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease presented with cutis verticis gyrata, digital clubbing, arthralgias, periosteal new bone formation and hyperhidrosis. That patient received celecoxib and pamidronate plus prednisolone, which reportedly resulted in a good response.

Gastric hypertrophy, gastric ulcers and even endocrine abnormalities have been described with PDP.14 Interestingly, GI symptoms and pathology have been found in patients with SLCO2A1 mutations.15 An associated condition has been described as chronic enteropathy associated with SLCO2A1 gene mutation (CEAS).16

CEAS was initially proposed as a diagnosis based on multiple intestinal ulcers accompanied by an SLCO2A1 mutation, but has since evolved into its own entity. CEAS is an autosomal recessive hereditary disease caused by SLCO2A1 mutations.17 It mostly occurs in women.11 Patients generally have some form of anemia and hypoproteinemia from persistent gastrointestinal bleeding and intestinal protein loss.18 Inflammatory markers, such as CRP, are usually normal or slightly increased. Because CEAS mimics ileal Crohn’s disease with respect to ileal ulcers and stenosis, it is often difficult to distinguish the two by clinical features alone.11

Treatments for chronic enteropathies, such as IBD, including 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), corticosteroids, azathioprine and anti-tumor necrosis factor-α antibody (anti-TNF-α), are often ineffective in CEAS. However, we found one report of improvement with azathioprine.18 A case report of a male patient with CEAS and PDP indicates he was eventually treated with 5-ASA.19

Conclusion

A diagnosis of PDP is often delayed due to different presentations, such as pachyderma, arthritis, enlarged distal extremities and even GI ulceration. CEAS should be considered in those with chronic enteropathy and SLCO2A1 gene mutation, and the therapy may differ from that for IBD. Patients may not respond well to treatment and different options may need to be explored, with minimal consensus on the available options, other than NSAIDs and, potentially, pamidronate.

The patient in our case report met the diagnostic criteria for PDP given the arthralgias, skin thickening and periosteal reaction, even though he did not have some of the other features, such as clubbing or cutis verticis gyrata, at the time of diagnosis. Genetic testing confirmed the diagnosis, with abnormalities in the SLCO2A1 gene, which also made CEAS a concern given his GI symptoms, especially findings related to the ileum. The patient has shown some response to methotrexate and anti-TNF-α medications. Since the implementation of this regimen, plus the addition of physical therapy and a Crohn’s disease exclusion diet, he has experienced improvement in joint swelling and pain.

Geoffrey E. Thiele, MD, is a third-year pediatric rheumatology fellow at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. He attended the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, for medical school and completed his residency at Phoenix Children’s Hospital, both of which cemented his interest in the field of pediatric rheumatology.

Geoffrey E. Thiele, MD, is a third-year pediatric rheumatology fellow at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. He attended the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, for medical school and completed his residency at Phoenix Children’s Hospital, both of which cemented his interest in the field of pediatric rheumatology.

Iris Reyhan, MD, is assistant professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Keck School of Medicine, and associate fellowship program director at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. She received her medical degree from Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel. She completed her residency training at Cohen Children’s Medical Center, Northwell Health, New York.

Iris Reyhan, MD, is assistant professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Keck School of Medicine, and associate fellowship program director at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. She received her medical degree from Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel. She completed her residency training at Cohen Children’s Medical Center, Northwell Health, New York.

References

- Sandoval AR, Flores-Robles BJ, Llanos JC, et al. Cutis verticis gyrata as a clinical manifestation of Touraine-Solente-Gole’ syndrome (pachydermoperiostosis). BMJ Case Rep. 2013 Jul 12:2013:bcr2013010047.

- Mobini M, Akha O, Fakheri H, et al. Pachydermoperiostosis in a patient with Crohn’s disease: Treatment and literature review. Iran J Med Sci. 2018 Jan;43(1):81–85.

- Yang JJ, Sano DT, Martins SR, et al. Primary essential cutis verticis gyrata – case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014 Mar–Apr;89(2):326–328.

- Martinez-Lavin M. Miscellaneous noninflammatory musculoskeletal conditions. Pachydermoperiostosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011 Oct;25(5):727–734.

- Gupta M, Lehl SS, Singh R, et al. Touraine-Solente-Gole’ syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2011 Sep 28:2011:bcr0820114605.

- Rahaman SH, Kandasamy D, Jyotsna VP. Pachydermoperiostosis: Incomplete form, mimicking acromegaly. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2016 Sep-Oct;20(5):730–731.

- Ozdemir M, Yildirim S, Mevlitoğlu I. En coup de sabre accompanied by pachydermoperiostosis: a case report. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007 Mar-Apr;25(2):315–317.

- Castori M, Sinibaldi L, Mingarelli R, et al. Pachydermoperiostosis: An update. Clin Genet. 2005 Dec;68(6):477–486.

- Uppal S, Diggle CP, Carr IM, et al. Mutations in 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase cause primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy. Nat Genet. 2008 Jun;40:789–793.

- Nakazawa S, Niizeki H, Matsuda M, et al. Involvement of prostaglandin E2 in the first Japanese case of pachydermoperiostosis with HPGD mutation and recalcitrant leg ulcer. J Dermatol Sci. 2015 May;78:153–155.

- Umeno J, Esaki M, Hirano A, et al. Clinical features of chronic enteropathy associated with SLCO2A1 gene: A new entity clinically distinct from Crohn’s disease. J Gastroenterol. 2018 Aug;53(8):907–915.

- Kim HJ, Koo KY, Shin DY, et al. Complete form of pachydermoperiostosis with SLCO2A1 gene mutation in a Korean family. J Dermatol. 2015 Jun;42(6):655–657.

- Coggins KG, Coffman TM, Koller BH. The hippocratic finger points the blame at PGE2. Nat Genet. 2008 Jun;40:691–692

- Rim A, Samar B, Fourati H, et al. Hypertrophy of the feet and ankles presenting inprimary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy or pachydermoperiostosis: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012 Jan 24:6:31.

- Seta V, Capri Y, Battistella M, Bagot M, Bourrat E. Pachydermoperiostosis: The value of molecular diagnosis. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2017 Dec;144(12):799–803.

- Umeno J, Hisamatsu T, Esaki M, et al. A hereditary enteropathy caused by mutations in the SLCO2A1 gene, encoding a prostaglandin transporter. PLoS Genet. 2015 Nov 5;11(11):e1005581.

- Yuan L, Chen X, Liu Z, et al. Novel SLCO2A1 mutations cause gender differentiated pachydermoperiostosis. Endocr Connec. 2018 Aug 1;7(11):1116–1128.

- Eda K, Mizuochi T, Takaki Y, et al. Successful azathioprine treatment in an adolescent with chronic enteropathy associated with SLCO2A1 gene: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Oct;97(41):e12811.

- Tsuzuki Y, Aoyagi R, Miyaguchi K, et al. Chronic enteropathy associated with SLCO2A1 with pachydermoperiostosis. Intern Med. 2020;59(24):3147–3154.