The Case

A 35-year-old African American woman with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) with multi-organ involvement presented with a three-month history of an intensely pruritic scaling rash on her scalp.

Prior to this encounter, the patient had a complicated medical course requiring multiple hospital admissions, leading to the diagnosis of Class V lupus nephritis, myositis, renal and pulmonary thrombi, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and persistent discoid skin lesions (see Figures 1a and b). The patient’s medications for her SLE included prednisone 40 mg daily, hydroxychloroquine 400 mg daily and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) 3 g/day. At the time of the patient’s initial diagnosis of SLE, her antibody profile revealed ANA 1:160 (speckled), anti-dsDNA negative, anti-SSA 274 EU/Ml, anti-Smith 165 EU/mL and anti-RNP 189 EU/mL.

Throughout the course of several admissions, she complained of a persistent pruritic skin rash, which initially started on her arms and hands, with hyperpigmentation, peeling and a psoriasiform appearance. The skin biopsy from the forearm performed at the time of the SLE diagnosis was consistent with a lupus rash. With initiation of immunosuppressive therapy, both her rash and pruritus significantly improved. However, at subsequent hospitalizations due to possible medication nonadherence and underlying disease activity, her SLE worsened, and she required several courses of pulse corticosteroids. There was temporary improvement in her skin findings, only to be followed by recurrence of her symptoms.

Over the course of these admissions, her rash worsened and became crusted, eventually spreading to involve her scalp (see Figures 2a and b). This was puzzling to the medical service and raised suspicion for an opportunistic infection (e.g., bacterial superinfection, rare fungal infections or herpes simplex virus) and a possible adverse drug reaction. She was empirically treated with antibiotics and antiviral agents, without notable improvement.

This was followed by selective discontinuation of the patient’s medications in an attempt to identify the culprit of a possible adverse drug reaction. It was found that the patient’s rash would improve with cessation of MMF and return once her therapy was resumed. This led to a strong suspicion that MMF was the source of the allergic type skin rash, which was causing the intense itching and scaling.

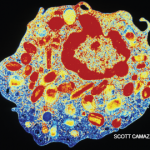

However, the diagnosis of scabies in several nurses in the ward prompted an evaluation of our patient for scabies. Microscopic analysis of scalp scrapings revealed hundreds of mites and scybala, consistent with a diagnosis of severe crusted scabies. The patient was treated with multiple doses of permethrin cream and ivermectin with resolution of the rash (see Figures 3a and b).

Diagnosis

Crusted scabies, formerly known as Norwegian scabies, is an uncommon parasitic infection caused by infestation of the superficial layers of the skin with the mite, Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis.1 The name Norwegian scabies originates from its first description in 1848 of a group of Norwegian leprosy patients who developed the crusted scabies variant.2

Unlike typical scabies, crusted scabies requires an inadequate host response to the arthropod mite, leading to a hyperinfestation state, with up to 2 million mites per person.3,4 This presentation usually occurs in patients with compromised immune systems, such as those on immunosuppressive therapy, infections with HIV or HTLV-1, or those with severe debilitation or cognitive dysfunction.1,5 Pruritis, caused by an allergic response to the mites within the skin, is a common manifestation of infection, which can lead to the diagnosis. However, in the immunocompromised patient, this urge to itch may be absent due to an altered immune response, which allows for heavy infestation.3,4

Crusted scabies is highly contagious and can be spread by minimal contact or indirect transmission through clothing or bedding. Classic scabies usually requires prolonged person-to-person contact and is rarely spread without direct contact.1 A classic infection of scabies has a mite load of about 10–15 mites per person; however, in crusted scabies, there are millions of mites underneath the skin, causing a crusted, scaly or even warty hyperkeratotic appearance of the skin.1,3

The presentation of crusted scabies is commonly limited to an isolated region of the body, such as the palms and soles, but infrequently involves the scalp. This atypical presentation can mimic many other conditions (e.g., dermatomyositis, psoriasis, discoid lupus) resulting in a delay in diagnosis.5 Prompt recognition of the condition is necessary because an outbreak can spread to those working close to the infected individual or even progress to an institution-wide infestation, as reported in our case.3 There is also heightened risk for secondary infections that could potentially lead to a life-threatening sepsis.2

The diagnosis of crusted scabies requires direct visualization of the mite with a light microscope under low power; however, false negatives can occur.

The diagnosis of crusted scabies requires direct visualization of the mite with a light microscope under low power; however, false negatives can occur. A mite may be visualized on a skin biopsy as well.1 Treatment for crusted scabies includes topical keratolytic therapy, topical scabicides and a multidose regimen of ivermectin depending on the severity of the condition.3,6

Crusted scabies is a relatively rare finding that needs to be considered as part of the differential diagnosis in immunosuppressed patients who develop a persistent, pruritic rash. As with our patient, symptoms can completely resolve with effective treatment and containment of the infestation.

Kenneth W. Van Dyke, DO, is a second-year clinical rheumatology fellow at Louisiana State University Health Science Center in New Orleans.

Jen K. Erbil, MD, is a rheumatologist at Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center in Baton Rouge, La. She completed her fellowship training at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans.

Harmanjot K. Grewal, MD, is an assistant professor of clinical medicine, Section of Rheumatology, at Louisiana State University Health Science Center in New Orleans.

Disclosures: Dr. Erbil has given a (nonbranded) presentation for Abbvie.

References

- Chosidow O. Scabies. N Engl J Med. 2006 Apr 20;354(16):1718–1727.

- Walton S, Beoukas D, Roberts-Thomson P, et al. New insights into disease pathogenesis in crusted (Norwegian) scabies: The skin immune response in crusted scabies. Br J Dermatol. 2008 Jun;158(6):1247–1255.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2010. Parasites: Scabies. http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies.

- Chosidow O. Scabies and pediculosis. Lancet. 2000 Mar 4;355(9206):819–826.

- Robers L, Huffam S, Walton, et al. Crusted scabies: Clinical and immunological findings in seventy-eight patients and a review of the literature. J Infect. 2005 Jun;50(5):375–381.

- Currie B, McCarthy J. Permethrin and ivermectin for scabies. N Engl J Med. 2010 Feb 25;362(8):717–725