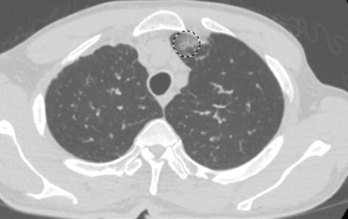

Figure 1. This chest CT shows new left upper lobe groundglass opacity.

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), also known as Churg-Strauss syndrome or allergic granulomatosis and angiitis, is a rare small- and medium-vessel vasculitis. This disease was first described by American pathologists Jacob Churg and Lotte Strauss in 1951.1

Although the vasculitis is often not apparent in the initial phases of the disease, EGPA can affect any organ system. It often manifests as peripheral blood eosinophilia, asthma and/or allergic rhinitis. In addition, patients frequently experience non-specific systemic findings, such as fever, weight loss, malaise, myalgias and arthralgias. Classified as an anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis, along with granulomatosis with polyangiitis and microscopic polyangiitis, EGPA is the least common of the three.2

EGPA has three clinical phases (i.e., allergic, eosinophilic and vasculitic), but not all patients will develop all phases or progress from one to the next sequentially.3 The most commonly involved organ in this disease is the lung, followed by the skin.4 Unlike many autoimmune diseases, EGPA does not exhibit a particular gender predominance.5 The mean age of onset is 40 years.5 Much of the underlying etiology and pathophysiology remains unclear.

Below, we report an interesting case in which a patient’s initial presentation of worsening shortness of breath in the setting of myocarditis led to a diagnosis of EGPA.

The Case

A 63-year-old man with a past medical history of prostate cancer (treated with radical prostatectomy), hyperlipidemia and asthma presented to our emergency department with a one-day history of worsening shortness of breath and dyspnea on exertion. The patient did not have any previous personal or family history of rheumatologic disease. Of note, he was diagnosed with asthma within one year of his initial presentation.

Two months earlier, the patient was evaluated by his primary care physician for watery diarrhea. His diarrhea had resolved, but over the course of the next two weeks, the patient noted worsening lower extremity numbness and tingling. Labs at that time revealed leukocytosis of 30.9×103/µL (50.3% eosinophils).

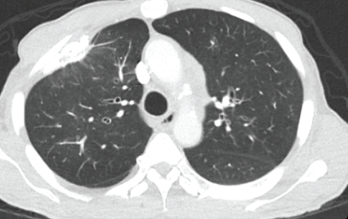

Figure 2. This chest CT shows improved aeration of the left upper lobe compared with Figure 1.

The patient’s complete blood count one year earlier had revealed a normal white blood cell (WBC) count with 5.1% eosinophils. The patient was hospitalized briefly for worsening leukocytosis and eosinophilia in the setting of thrombocytosis. He underwent extensive workups with hematology/oncology and infectious disease experts, all of which proved unremarkable. A computed tomography (CT) scan of his chest revealed densely calcified pleural plaques involving the anterior aspect of the lung’s right upper lobe with an adjacent parenchymal opacity. He refused further inpatient workup and was discharged on oral antibiotics and an oral prednisone taper.

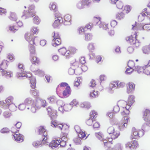

In the month preceding his presentation at our emergency department, the patient underwent further outpatient workup. A repeat chest CT demonstrated a new left upper lobe groundglass opacity with new mediastinal lymphadenopathy in addition to stable, upper right lobe, partially calcified, pleural thickening (see Figure 1). The patient continued to experience worsening paresthesias of his feet bilaterally (the left more so than the right), and an autoimmune workup (see Table 1) demonstrated elevated inflammation markers. A bone marrow biopsy revealed reactive eosinophilia without evidence of underlying leukemia or lymphoproliferative process.