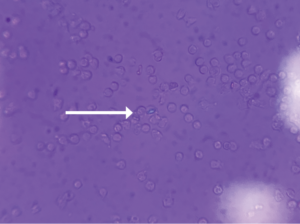

FIGURE 1 (click to enlarge): Intracellular calcium pyrophosphate crystal on polarized light microscopy.

Calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition disease (CPPD) is an arthritis caused by the accumulation of calcium pyrophosphate crystals. Despite a prevalence of 4–7% among the adult population in Europe and the U.S., it has remained a relatively under-recognized disease owing to its many clinical presentations.1 CPPD may cause an acute mono/oligoarthritis, which may mimic gout or septic arthritis; a chronic arthritis, which may mimic a variety of chronic arthritides (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis); or a systemic disease, which may mimic sepsis or meningitis. An estimated 25% of initial presentations of CPPD mimic gout or septic arthritis.1 Severity and timing of pain may truly mimic gout, but acute presentations of CPPD are typically less disabling and take longer for pain to reach peak intensity than gouty attacks.2

Although the formal diagnostic criteria have been defined, considerable practical challenges in the diagnosis of CPPD remain. Compared with urate crystals in the context of gout, calcium pyrophosphate crystals are smaller and less birefringent via light microscopy, resulting in less reliability and higher interobserver variability.3

We describe the case of a 78-year-old man with a history of gout who presented with acute-onset unilateral knee pain, initially thought to be due to a septic joint, a condition also known as pseudosepsis, an inflammatory arthritis that cannot be differentiated from septic arthritis on the basis of history, clinical presentation or serum lab values.4

Case Presentation

A 78-year-old man presented to the hospital with a one-day history of severe right knee pain and swelling. He was completely unable to move the knee or bear weight and was brought in via wheelchair. His pain was exacerbated by movement and light touch. He reported an episode of nausea and vomiting just before his arrival that was presumably due to the pain. The patient denied fevers, chills, night sweats, shortness of breath, chest pain, abdominal pain and diarrhea.

The patient’s medical history was significant for gout, myelodysplastic syndrome and stage 3 chronic kidney disease.

His knee was swollen and palpably warm, but without overlying erythema. His range of motion in the knee was limited due to pain. Initial lab tests revealed a C-reactive protein (CRP) of 295 mg/L (reference range [RR]: 0–5.0 mg/L) and a white blood cell (WBC) count of 14.6k/uL (RR: 3.9–10.7k/uL) with neutrophilic predominance. His right knee X-ray revealed mild tricompartmental joint space narrowing with a large joint effusion but no chondrocalcinosis. Arthrocentesis showed 47,628 nucleated cells (92% segmented neutrophils) and 21,000 red blood cells (RBCs) with no crystals seen via light microscopy. Synovial fluid gram stain was was unrevealing and bacterial cultures yielded no growth. Additional 16s and 18s polymerase chain reaction application studies for the detection of bacterial DNA were negative.

High index of suspicion for CPPD is needed in patients older than 65, even in light of other data that may be mistakenly interpreted as evidence of septic joint.

He was immediately taken to the operating room and underwent arthroscopic washout with partial synovectomy. The intraoperative synovial fluid culture failed to yield a culprit organism, although purulent material was noted. After some initial postoperative improvement, his CRP rose to 138 mg/L, prompting an incision and drainage with repeat negative synovial fluid cultures and no bacteria seen in synovial tissue sampling.

He completed a three-week course of antibiotics. However, he remained admitted, with a complex and prolonged hospitalization. Two months later, on hospital day 73, the patient developed acute left knee pain and swelling. Arthrocentesis revealed 42,880 nucleated cells (83% segmented neutrophils), 3,000 RBCs, negative fluid cultures and, once again, no crystals seen via light microscopy. Antibiotics were not initiated at this time given the concern for marrow suppressive effects and the inability to isolate an organism on synovial tissue or fluid culture. He had slow resolution of left knee pain and swelling with conservative pain management.

Three weeks later he had acute worsening of his left knee pain, for which a rheumatologist was consulted. An X-ray of the left knee showed chondrocalcinosis. The serum uric acid level was 8.1 mg/dL (RR: 3.5–7.2 mg/dL). Arthrocentesis revealed 150,927 nucleated cells (90% segmented neutrophils) and 17,000 RBCs. Synovial fluid gram stain and bacterial culture were again negative.

On our manual review of the synovial fluid, positively birefringent crystals were seen with a polarizing microscope within neutrophils, meeting formal criteria for the diagnosis of acute monoarticular CPPD arthropathy (see Figure 1). Anintra-articular steroid injection was performed. Arthrocentesis was repeated two days after the steroid injection, which revealed 80,600 nucleated cells (64% segmented neutrophils) and repeat visualization of CPPD crystals. He completed a three-day course of anakinra and was discharged home on hospital day 94.

Discussion

The differential diagnosis of acute-onset monoarticular joint pain is relatively limited. It may remain a diagnostic challenge, however, in cases where history, physical and serum lab values fail to adequately support or refute a noninfectious vs. an infectious cause—cases aptly termed pseudosepsis.

In addition to CPPD, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, Behçet’s disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis have all been reported to present as pseudoseptic arthritis.5 Despite potential fever and leukocytosis, synovial fluid gram stain and culture are repeatedly negative. In one retrospective study across more than two and a half decades at one center, 19% of suspected septic arthritis cases were culture negative.6

Several studies have examined the role of synovial WBC count and the percentage of polymorphonuclear cells in the diagnosis of septic arthritis. A leukocyte count of >100,000 cells/mm3 is highly suggestive of septic joint (likelihood ratio [LR]: 28.0; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 12.0–66.0), and a polymorphonuclear cells percentage of at least 90% further adds to the likelihood (LR: 3.4; 95% CI: 2.8–4.2).7 The decision to halt antibiotics in light of negative cultures ultimately comes down to clinical judgment, but the presence of persistently negative cultures should clue the clinician in to an alternate diagnosis.6

In our case, antibiotics were continued after our patient’s initial presentation despite repeated negative cultures and synovial tissue sampling with no bacteria noted. Because no crystals were seen on microscopy and diagnostic uncertainty remained, the decision was made to treat for septic arthritis given its significant morbidity and mortality. What may have given an infectious etiology more credence was the purulent material noted during the first joint washout and the patient’s immunosuppressed state. However, it’s important to note the possibilityof nonbacterial causes for such a finding, as previously described in leukemia and parvovirus-associated pseudosepsis.6

A patient’s promising response to washout and antibiotics is also unreliable as confirmation for an infected joint as occurred in this case. Improvement following antibiotics may be due to their general anti-inflammatory effect rather than their antimicrobial effects.6

The patient’s new symptoms on the contralateral side approximately 2.5 months into his hospitalization were compellingly similar to his initial presentation, leading us to believe that CPPD arthropathy was responsible for both instances of his biphasic course. Notably, many observers may have initially overlooked the presence of calcium pyrophosphate crystals, requiring further analysis. The EULAR (the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology) highlights that proper training is crucial for the identification of crystals—even one or a few crystals are clinically significant.8 The absence of chondrocalcinosis on the patient’s right knee is also unreliable as this radiologic finding lacks sensitivity and specificity.8

• Pseudosepsis is an inflammatory arthritis with sterile synovial gram stain and culture that cannot be differentiated from septic arthritis on the basis of history, clinical presentation or serum lab values.

• CPPD has been known to mimic several types of arthritis and systemic conditions due to its varying clinical phenotypes, often resulting in delayed correct diagnosis and inappropriate or over treatment.

• Although a synovial leukocyte count of >100,000 cells/mL is highly suggestive of a septic joint, this does not rule out the diagnosis of a crystalline disease. The presence of persistently sterile cultures should clue the clinician in to an alternate diagnosis.

Conclusion

This case adds to the many atypical presentations described across the CPPD continuum and highlights the importance of early entertainment of its possibility to avoid unnecessary harm. Our patient remained in the hospital for presumed septic arthritis, which increased his risk for hospital-associated complications that resulted in increased morbidity.

It is important to underscore the clinician’s responsibility to always rule out infection while pursuing other possible etiologies. High index of suspicion for CPPD is needed in patients older than 65, even in light of other data that may be mistakenly interpreted as evidence of septic joint, including a high synovial WBC count, absence of chondrocalcinosis and improvement on antibiotics, as we observed in our patient.

Hassan Fakhoury, BS, is a student at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn.

Erin Chew, MD, is a fellow in the Department of Rheumatology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

Narender Annapureddy, MBBS, is an associate professor of medicine, Department of Rheumatology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

References

- Rosenthal AK, Ryan LM. Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease. N Engl J Med. 2016 June 30;374(26):2575–2584.

- McCarty DJ. Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease—1975. Arthritis Rheum. 1976 May-Jun;19 Suppl 3:275–285.

- Gordon C, Swan A, Dieppe P. Detection of crystals in synovial fluids by light microscopy: Sensitivity and reliability. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989 Sep;48(9):737–742.

- Oppermann BP, Cote JK, Morris SJ, Harrington T. Pseudoseptic arthritis: A case series and review of the literature. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2011;2011:942023.

- Paul P, Paul M, Dey D, et al. Pseudoseptic arthritis: An initial presentation of underlying psoriatic arthritis. Cureus. 2021 Apr 24;13(4):e14660.

- Eberst-Ledoux J, Tournadre A, Mathieu S, et al. Septic arthritis with negative bacteriological findings in adult native joints: A retrospective study of 74 cases. Joint Bone Spine. 2012 Mar;79(2):156–159.

- Margaretten ME, Kohlwes J, Moore D, Bent S. Does this adult patient have septic arthritis? JAMA. 2007 Apr 4;297(13):1478–1488.

- Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, et al. European League Against Rheumatism recommendations for calcium pyrophosphate deposition. Part I: Terminology and diagnosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 Apr;70(4):563–570.