A 24-year-old woman presented to our rheumatology office in 2017 with a blotchy purple rash on her arms and legs. She reported no history of miscarriage or blood clots.

The rash pattern was concerning for livedo reticularis or livedo racemosa, and she was noted to have an anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:160 with a speckled pattern and an elevated anti-Ro/SSA antibody greater than 8.0; however, antiphospholipid antibodies were not identified. Undifferentiated connective tissue disease was suspected based on her history of Raynaud’s phenomenon, a positive ANA, self-reported fatigue and elevated anti-Ro/SSA antibodies. She was placed on hydroxychloroquine.

She was also noted to have mild leukopenia and was seen by a hematologist, who believed her leukopenia was related to an underlying autoimmune condition.

The patient’s dermatologist biopsied her forehead, with results consistent with rosacea, and a biopsy of her thigh was noted to be supportive of livedo reticularis. At this time, the patient continued to take hydroxychloroquine because she felt it was helping her fatigue.

Over the course of 2018 into 2019, our patient’s livedo worsened, spreading to cover her entire body. Continued serologic monitoring was remarkable for elevated anti-Ro/SSA antibodies and a low-positive ANA. An evaluation for antiphospholipid antibodies remained negative. The test for anti-double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (dsDNA) antibodies was also negative, and her complements were normal.

In May 2019, the patient presented to an emergency department with sudden-onset right upper extremity weakness and numbness. She initially believed the symptoms were caused by a “pinched nerve”; however, when her arm became limp, she went immediately to the local emergency department.

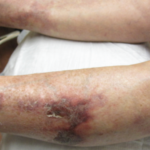

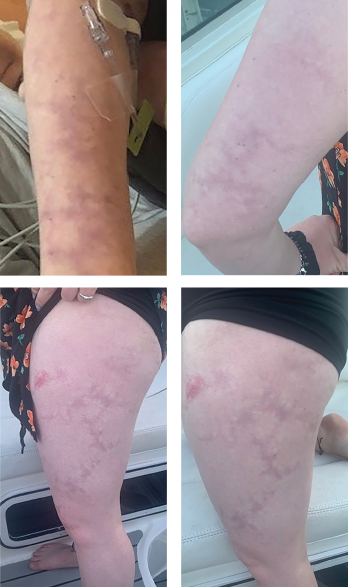

Livedo racemosa, a cutaneous finding characterized by a persistent, erythematous or violaceous discoloration of the skin, in a broken, branched, discontinuous and irregular pattern, is apparent on the patient’s arms and legs.

Upon arrival, the patient was found to have a score of 2 on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain demonstrated an acute left prefrontal gyrus infarct, with noted additional punctate foci of fluid-attenuated inversion recovery intensity within the cerebral white matter bilaterally.

A computed tomography angiography of her head and neck was nonrevealing, as was a magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) of her head. No evidence of stenosis was apparent on an MRA of her neck.

She was administered 325 mg of aspirin, as well as a statin, for stroke prevention by the consulting neurologist.

Transesophageal echocardiography failed to demonstrate a patent foramen ovale or intracardial clot. Laboratory evaluation did not demonstrate evidence of vasculitis or a hypercoagulable state.

After discharge, the patient was initially followed by the neurology practice that she saw in the hospital; she subsequently transitioned care to a neurologist in her home area.

Upon returning home following her stroke, she returned to our practice. The patient’s age, livedo and middle cerebral artery infarct, as well as her nonrevealing workup on repeat antiphospholipid antibody labs and hypercoagulable studies, were concerning for Sneddon syndrome.

Due to the concern for further strokes without a known associated cause, a dermatologist was contacted to perform a repeat skin biopsy, this time with larger margins. The biopsy demonstrated histological findings characteristic of Sneddon syndrome, with obliterative vasculopathy, and changes that included fibrous replacement of medium caliber vascular structures with focal recanalization.

The case was discussed with the patient’s dermatologist, who agreed that based on evidence of a pattern consistent with livedo racemosa (see Figures 1–4, opposite) and characteristic biopsy findings, Sneddon syndrome was a concern.

The patient’s case was discussed with her current hematologist, who agreed that anticoagulation was needed.

The patient has been taking warfarin and continued to have close follow-up with subspecialists. She has not had any further infarcts or events. The patient completed outpatient physical and occupational therapy, but continues to have residual right-hand deficits, including clumsiness, stiffness and loss of fine motor function.

Discussion

Sneddon syndrome is a rare, non-inflammatory vasculopathy, typically characterized by livedo racemosa, as well as such complications as cerebral infarcts or transient ischemic attacks that may go unrecognized prior to diagnosis.1

Livedo racemosa often presents years prior to cerebrovascular involvement; however, a case report of Sneddon syndrome without livedo racemosa does exist.1,2 Sneddon syndrome is estimated to occur in four in 1 million patients, generally women, with an onset between 20 and 42 years of age.2 Sneddon syndrome may present with or without antiphospholipid antibodies.3,4

Given the presentation and complications associated with this syndrome, multiple subspecialties are often necessary to establish a diagnosis, including neurologists, dermatologists, hematologists and rheumatologists.1 In this patient’s case, multidisciplinary care coordination was vital, and a team-based approach led to the recognition of her constellation of symptoms as possible Sneddon syndrome, prompting a repeat biopsy.

This case further highlights that larger biopsies may be necessary to demonstrate histologic evidence of livedo racemosa, which may help establish the diagnosis of Sneddon syndrome.4

In patients presenting with livedo racemosa, Sneddon syndrome should be included in the differential diagnosis, especially due to the high impact of potential disease complications.

It also is important to keep in mind that a large number of disease processes can be associated with livedo racemosa, including systemic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, polyarteritis nodosa and cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, among others. These other diagnoses must be ruled out by further evaluation, including clinical and laboratory testing, prior to a diagnosis of Sneddon syndrome.

Overall, more evidence is needed to support specific therapy recommendations in patients with Sneddon syndrome. Hydroxychloroquine has previously been reported to have theoretical benefit in patients with Sneddon syndrome due to its anti-thrombotic properties and ability to prevent endothelial dysfunction.1

There is a paucity of data to support the use of anticoagulation over antiplatelet therapy in patients with Sneddon syndrome who lack antiphospholipid antibodies. The decision on which therapy to use should be made on a case-by-case basis.

Further, given that patients most likely to be affected by Sneddon syndrome are women of childbearing age, the use of anticoagulants, such as warfarin, may be challenging. Warfarin is contraindicated in pregnancy due to its teratogenic potential and ability to induce spontaneous abortion, fetal hemorrhage and fetal death.6 Emphasis on effective contraceptive methods in patients treated with warfarin is vital. In patients who wish to start a family, careful consideration of the risks associated with temporary discontinuation of warfarin or use of low molecular-weight heparin is warranted.

Conclusion

Rheumatologists can play an important role in the diagnosis of Sneddon syndrome. In patients presenting with livedo racemosa, Sneddon syndrome should be included in the differential diagnosis, especially due to the high impact of potential disease complications. Additionally, when obtaining biopsies of livedo racemosa to investigate for histopathological evidence of Sneddon syndrome, an important consideration is whether the biopsied area is large enough for an accurate diagnosis.

It is vital to keep in mind the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with generalized livedo racemosa without evidence of positive antiphospholipid syndrome, especially in the context of known ischemic events. The lack of recognition of this rare syndrome can mean the difference between preventive anticoagulation and potential catastrophic events.

Emily Jean Katz, PA-C, is a physician assistant practicing rheumatology at the Center for Rheumatology, Saratoga Springs, N.Y.

Emily Jean Katz, PA-C, is a physician assistant practicing rheumatology at the Center for Rheumatology, Saratoga Springs, N.Y.

Kelsey Hennig, PharmD, BCPS, is a clinical assistant professor at Binghamton University, New York. She previously completed a PGY-1 pharmacy practice residency at St. Joseph’s Health, Syracuse, N.Y., and a PGY-2 ambulatory care pharmacy residency at Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, New York.

Mitchell Miller, PharmD, is a clinical pharmacy specialist in population health for Bassett Healthcare Network. He completed two years of post-graduate residency training, spending one year at St. Peter’s Hospital, Albany, N.Y., and another at Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences.

Jessica Farrell, PharmD, is a clinical pharmacist practicing at the Center for Rheumatology and an associate professor in the Department of Pharmacy Practice at Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences. Dr. Farrell is also a member of the ACR Government Affairs Committee.

Takeaways

- A diagnosis of Sneddon syndrome is best made via a multidisciplinary approach.

- Biopsy areas must be large enough to appreciate signs of Sneddon syndrome.

References

- Cleaver J, Teo M, Renowden S, et al. Sneddon syndrome: A case report exploring the current challenges faced with diagnosis and management. Case Rep Neurol. 2019 Dec 16;11(3):357–368.

- Wu S, Xu Z, Liang H. Sneddon’s syndrome: A comprehensive review of the literature. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014 Dec 13;9:215.

- Tietjen GE, Al-Qasmi MM, Gunda P, et al. Sneddon’s syndrome: Another migraine-stroke association? Cephalalgia. 2006 Mar; 26(3):225–232.

- Francès C, Papo T, Wechsler Bet al. Sneddon syndrome with or without antiphospholipid antibodies. A comparative study in 46 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1999 Jul;78(4):209–219.

- Bolayir E, Yilmaz A, Kugu N, et al. Sneddon’s syndrome: Clinical and laboratory analysis of 10 cases. Acta Med Okayama. 2004 Apr; 58(2):59–65.

- Coumadin (warfarin) prescribing information. Bristol-Meyers Squibb Company. 2019 Dec.