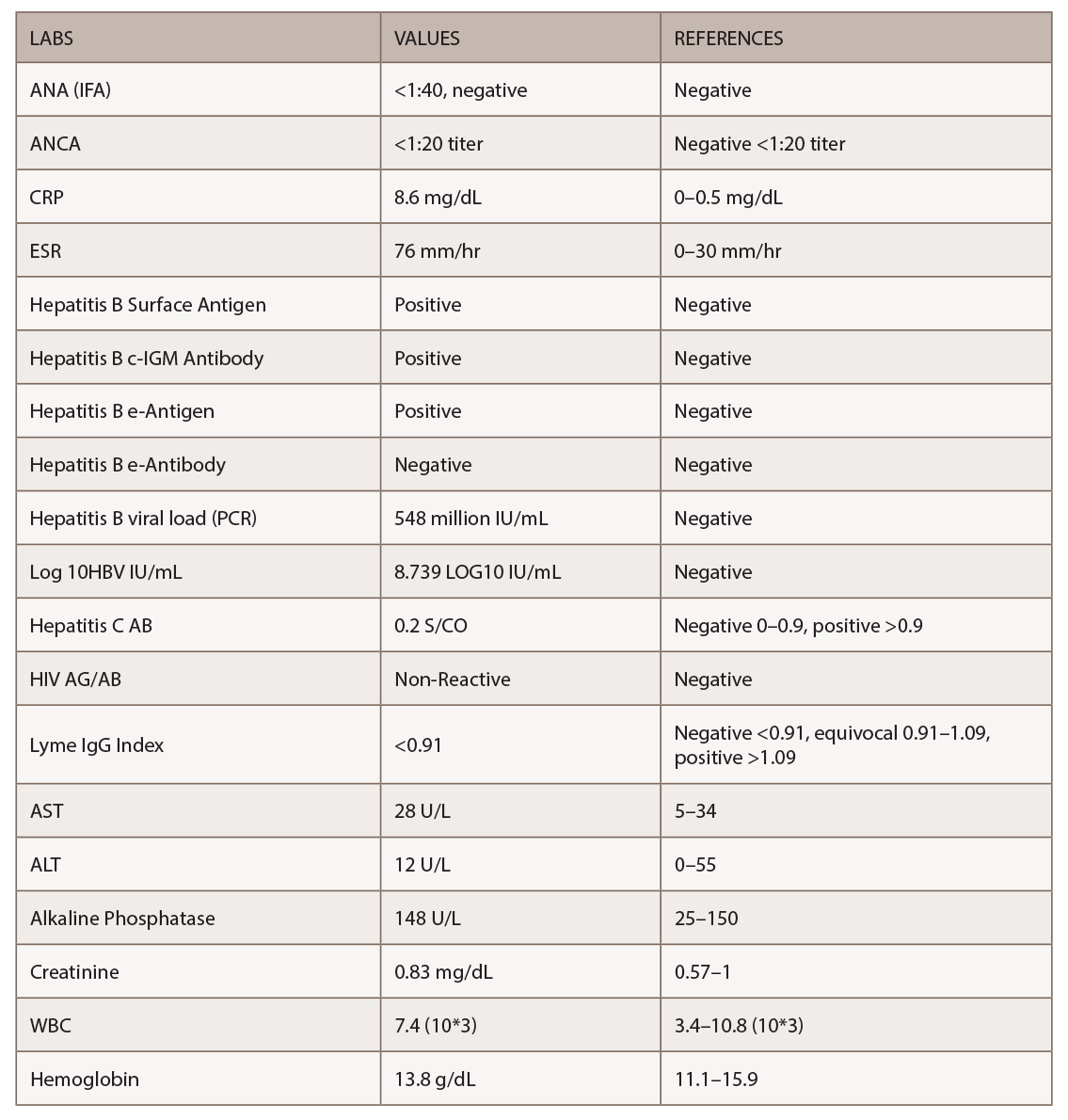

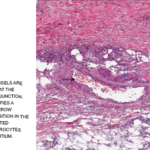

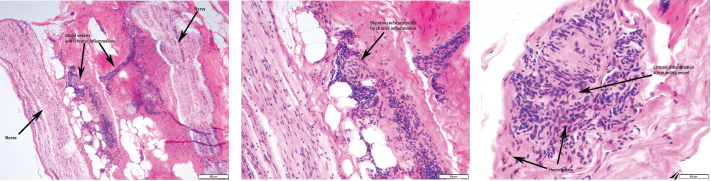

Figures 1, 2 & 3 (from left): The sural nerve biopsy showed vasculitis, perivascular cuffing, and vessels with inflammation and hemosiderin.

HBV-associated PAN was felt to be likely in this patient with mononeuritis multiplex, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), HBV viral load and vasculitis on sural nerve biopsy. The patient was promptly started on antiviral treatment with 0.5 mg of entecavir daily. She also underwent five sessions of plasmapheresis. Corticosteroids were tapered over the ensuing two weeks.

The patient saw improvement in the burning pain in her right leg and foot, and improvement in her left-hand weakness with the plasmapheresis sessions. The plan upon hospital discharge was to continue antiviral therapy and complete a few more plasmapheresis sessions. Unfortunately, she failed to show up for outpatient appointments and was eventually lost to follow-up.

Discussion

PAN is a systemic necrotizing vasculitis that primarily affects medium-size arteries. It was first described by Kussmaul and Meier in 1866.1 It may be primary or triggered by certain infections, the most common being HBV. PAN affects all racial groups, ages and genders.2 The current annual incidence ranges from 0–1.6 cases per million inhabitants in European countries.2 Once widespread, PAN has become rare over the years with the availability of HBV vaccination and antiviral therapies. Currently, less than 5% of patients with PAN in developed countries are HBV positive.2

The mechanism most commonly implicated is immune complex deposition leading to vascular injury. Interestingly, glomerulonephritis, a characteristic immune-complex mediated lesion, does not usually appear in PAN.2 Although viral antigens or immune complexes are rarely found in the vessel walls of PAN, a close relationship between PAN and HBV exists, although the frequency has declined. Moreover, the frequency of non-HBV-associated PAN has also decreased. Other causes of PAN include hepatitis C, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), cancers and hematological diseases.1

Signs & Symptoms

Clinical features of PAN encompass a wide constellation. Symptoms may be indolent, but life-threatening complications can occur. Constitutional symptoms, neurological manifestations and skin involvement are the most common findings.3 Table 2 (opposite) highlights the clinical symptoms in a retrospective study by Guillevin et al. of 115 patients with HBV-associated PAN.4 Unspecific constitutional symptoms include malaise, weight loss, fever, arthralgia and myalgia.2 Half of patients suffer myalgias, which may be intense, diffuse and occur spontaneously or after applying pressure.1 Arthralgias can predominantly affect the knees, ankles, elbows and wrists. Peripheral neuropathy, frequently manifested as mononeuritis multiplex, is a common finding in PAN.2 The preferentially involved nerves include the superficial peroneal, sural, radial, cubital and median.1 (Our patient had sural and median nerve involvement in an asymmetric and distal distribution.) Skin involvement includes purpura, livedoid lesions, subcutaneous nodules and necrotic ulcers.2 The most common cutaneous finding is palpable purpura, often necrotic and corresponding to subcutaneous small-vessel vasculitis.1 Our patient did not have any cutaneous manifestation.

Renal involvement consists of tissue infarction or hematoma. The hematoma is usually produced by the rupture of renal microaneurysms.2 Kidney infarcts may be clinically silent or produce micro- or macrohematuria, and mild to moderate proteinuria. Pagnoux et al. noted that peripheral neuropathy, recent onset hypertension (resulting from intrarenal artery involvement), skin nodules, orchitis and gastrointestinal manifestations were more frequent in patients with HBV-associated PAN than in patients with non-HBV-associated PAN.3

The time frame from HBV infection to PAN development is variable but generally occurs soon after infection. The Guillevin et al. study noted most patients became infected with HBV during the year preceding PAN and late occurrences are rare.4 Our patient’s HBV serologies indicated recent active infection and replication.

The usual response to HBV infection is the development of jaundice, preceded by systemic manifestations such as arthralgia, urticaria, migraines and a dramatic increase in transaminases.4 This constitutes the normal immune reaction to clear the virus.4 PAN seems to exacerbate the prodromal phase, and transaminase levels are only moderately elevated.4 Thus, PAN may delay or suppress the usual manifestation of acute HBV infection, as was noted in our patient.

In acute hepatitis, virus replication stops after a few weeks, when antibodies appear. Antibody production is first directed against HBeAg and then against HBsAg.4 This constitutes seroconversion. As noted by Guillevin et al., seroconversion is low in PAN.4 This suggests that in HBV-infected patients who develop PAN, active viral replication continues for a longer period than in HBV patients without PAN. We saw this in the HBV serologies obtained from our patient. This also forms the rationale for HBV-associated PAN utilizing antiviral therapy as the cornerstone of treatment, as opposed to non-infectious PAN in which immunosuppressive agents are utilized.

There are no specific lab tests to diagnose PAN. ESR and CRP are commonly elevated. Chronic anemia and leukocytosis frequently occur.2 Eosinophilia is occasionally present, which should prompt an evaluation for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Viral hepatitis serologies should be systematically sought.1 Hepatitis is frequent, but usually mild, and sometimes can be asymptomatic and thus misdiagnosed.4 Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) tests are typically negative in PAN. In the Guillevin et al. study, ANCA was not detected in 72 patients tested.4 In this same study, cryoglobulins were found in four of those 72 patients (5.6%) and monoclonal gammopathy in two patients (neither developed myeloma or Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia). AST and ALT levels were normal in 38 (33%) and 30 (26%) patients, respectively.4