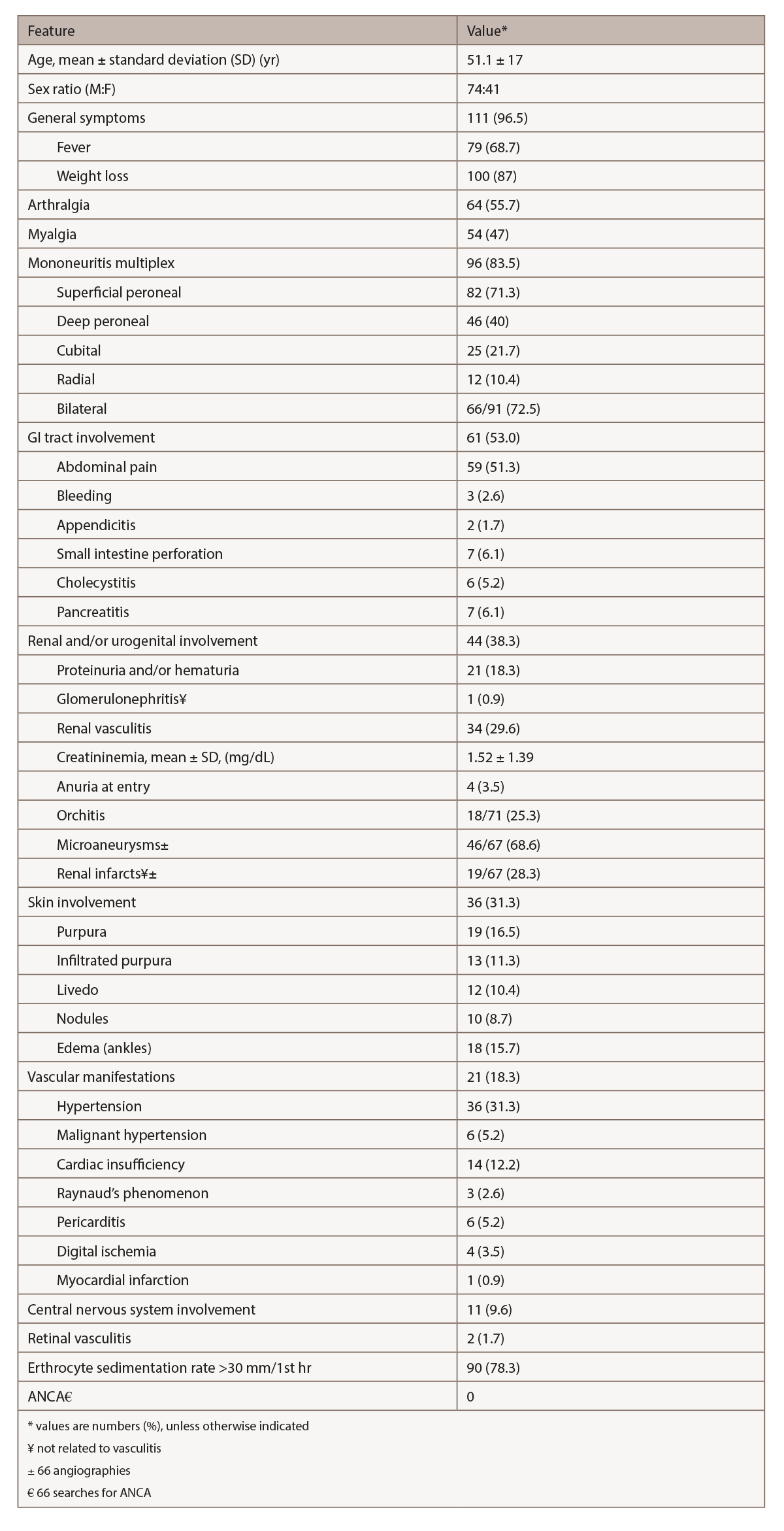

(click for larger image) Table 2: Relevant Clinical & Laboratory Features in 115 Patients with HBV-PAN4

Biopsy is crucial to confirm the diagnosis of vasculitis and exclude other disorders. To achieve the maximum diagnostic yield, biopsy must be directed to symptomatic sites (i.e., muscle, sural nerve, skin or testicle).2 In the Pagnoux et al. study of 384 patients with PAN, combined muscle and nerve biopsies in symptomatic patients provided histological confirmation of vasculitis in 83%, whereas isolated muscle biopsies demonstrated vascular inflammation in 65%.2,3 When biopsies of muscle or nerve are blindly performed, vasculitis appears in up to one-third.2

Because renal involvement results from ischemia and the risk of hematoma from microaneurysm rupture exists, kidney biopsy is not recommended.1 Muscle biopsy should be performed at the site of myalgias or in the gastrocnemius or peroneal muscles.1 The diagnostic sensitivity of biopsies of proximal muscles (deltoid or quadriceps) is lower than those performed in distal muscles.1 A deep skin biopsy can show medium-size vessel involvement in patients with infiltrated necrotic purpura.1

The histological hallmark of PAN is focal segmental necrotizing vasculitis of medium-size arteries, less commonly arterioles, and only rarely capillaries and venules.1 The characteristic histological feature is the coexistence of necrotizing vasculitis and a healed lesion or normal arteries in different tissues or different parts of the same tissue.1 The acute phase of arterial wall inflammation is characterized by fibrinoid necrosis of the media and intense pleomorphic cellular infiltration, with neutrophils and variable numbers of lymphocytes and eosinophils.1

Angiography can help in visualizing microaneurysms and stenosis in medium-size arteries.1 Typical arteriographic lesions in PAN are arterial saccular or fusiform microaneurysms (1–5 mm in diameter), usually coexisting with stenotic lesions and predominantly in kidney, mesenteric and hepatic artery branches.2 An argument can be made that when characteristic angiographic lesions are detected in the appropriate clinical context, the diagnosis of PAN can be made even in the absence of histological confirmation.2

Our case was atypical: No characteristic PAN lesions were visible on angiography. Aside from mononeuritis multiplex, the patient did not demonstrate any other manifestation of systemic vasculitis. Thus, we pursued sural nerve biopsy.

Recommendation: When evaluating a potential PAN case, obtain both angiography and a biopsy of an involved site (if possible) to maximize the diagnostic yield.

The original ACR-proposed classification criteria for PAN in 1990 had important limitations. It did not consider microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) as a separate entity, and did not take ANCA testing into consideration.2 The 1994 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference did differentiate PAN from MPA, and the negativity of ANCA in PAN was emphasized in the updated 2012 Chapel Hill consensus definitions.2

Therapy

Treatment for HBV-associated PAN comprises a strategy that combines the clearance of immune complexes and suppression of HBV replication. In these cases, corticosteroids are usually begun to control potentially life-threatening organ damage from vasculitis.4 However, corticosteroids should be administered only for a short period to not prolong immune suppression in the face of HBV replication.

For life-threatening cases, plasma exchange may be useful, in addition to the use of antiviral agents. Plasma exchange removes the immune complexes, which are the major determinant of vessel inflammation. The frequency and number of plasma exchange sessions can be individualized for each case.

The antiviral agent targets the source of immune complex development by diminishing the viral load, eventually stopping viral replication and facilitating seroconversion.

This strategy of combining plasma exchange and antiviral therapy has been borne out in studies conducted by the French Vasculitis Study Group. The seroconversion rate is significantly higher in HBV-PAN patients given the antiviral strategy than in those treated with immunosuppressants, and those receiving the latter regimens had higher probabilities of relapsing.4 The benefits of the antiviral strategy also continue for the long term, lowering the risk of cirrhosis and carcinoma.