Jarun Ontakrai / shutterstock.com

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) associated polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is an increasingly rare vasculitis in developed countries due to advances in HBV vaccination and antiviral therapy. However, the condition does persist, and rheumatologists should consider it when evaluating vasculitis cases.

Below, we discuss a case that illustrates the varied clinical presentations PAN can encompass. A high index of suspicion, along with a systematic workup, led to the diagnosis.

We then discuss a treatment strategy that differs from non-HBV-associated PAN.

The Case

A 53-year-old Caucasian woman with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hypothyroidism presented to the hospital with a three-week history of stabbing pain and burning in her right leg from her shin down to her toes. She complained of an inability to plantar or dorsiflex her right foot and could not bear weight on it. She also complained of weakness, numbness and burning in her left hand occurring over the same period. She denied any rash, chest pain, shortness of breath or abdominal pain. She denied any hematemesis, hemoptysis or hematochezia. She did have a 20-year cigarette smoking history, but denied any illicit or intravenous drug use.

A computed tomography scan of her brain was unremarkable. An X-ray of her right foot and left hand was normal, and non-contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of her thoracic and lumbar spine revealed no central canal stenosis or neuroforaminal narrowing.

The patient’s vital signs were stable. The physical exam was notable for normal muscle strength in her right, upper extremity and left, lower extremity. However, with her left hand, the patient had difficulty closing her thumb, index and middle finger due to pain and weakness. She had significant hyperalgesia to even light touch to her right lateral shin, ankle and foot. She had a right foot drop. A gait exam was deferred. She did not have any rash, and the rest of the physical exam was normal.

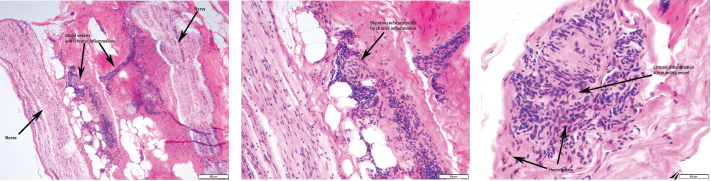

Mononeuritis multiplex was suspected, and she was started on 1 g daily methylprednisolone intravenously for three days while the workup was underway. Magnetic resonance imaging and angiogram of her brain showed patent cerebral vessels and no evidence of stroke. Significant lab results appear in Table 1.

Given the positive HBV serologies, elevated inflammatory markers and mononeuritis multiplex, we suspected PAN. The HBV viral load was extremely high at 548 million IU/mL.

Interestingly, an abdominal aortogram and bilateral, lower extremity arteriogram did not show any abnormalities in her abdominal or renal vessels. The bilateral, lower extremity arteriogram demonstrated normal flow down to her ankles. Distal arch occlusive disease was noted, but with no acute cutoff to suggest vasculitis, and the changes were consistent with her longstanding smoking.

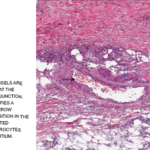

Given the non-diagnostic arteriogram and continued suspicion for polyarteritis nodosa, the decision was made to pursue a right sural nerve biopsy. The sural nerve biopsy did show vasculitis on pathology (see Figures 1, 2 & 3).

Figures 1, 2 & 3 (from left): The sural nerve biopsy showed vasculitis, perivascular cuffing, and vessels with inflammation and hemosiderin.

HBV-associated PAN was felt to be likely in this patient with mononeuritis multiplex, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), HBV viral load and vasculitis on sural nerve biopsy. The patient was promptly started on antiviral treatment with 0.5 mg of entecavir daily. She also underwent five sessions of plasmapheresis. Corticosteroids were tapered over the ensuing two weeks.

The patient saw improvement in the burning pain in her right leg and foot, and improvement in her left-hand weakness with the plasmapheresis sessions. The plan upon hospital discharge was to continue antiviral therapy and complete a few more plasmapheresis sessions. Unfortunately, she failed to show up for outpatient appointments and was eventually lost to follow-up.

Discussion

PAN is a systemic necrotizing vasculitis that primarily affects medium-size arteries. It was first described by Kussmaul and Meier in 1866.1 It may be primary or triggered by certain infections, the most common being HBV. PAN affects all racial groups, ages and genders.2 The current annual incidence ranges from 0–1.6 cases per million inhabitants in European countries.2 Once widespread, PAN has become rare over the years with the availability of HBV vaccination and antiviral therapies. Currently, less than 5% of patients with PAN in developed countries are HBV positive.2

The mechanism most commonly implicated is immune complex deposition leading to vascular injury. Interestingly, glomerulonephritis, a characteristic immune-complex mediated lesion, does not usually appear in PAN.2 Although viral antigens or immune complexes are rarely found in the vessel walls of PAN, a close relationship between PAN and HBV exists, although the frequency has declined. Moreover, the frequency of non-HBV-associated PAN has also decreased. Other causes of PAN include hepatitis C, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), cancers and hematological diseases.1

Signs & Symptoms

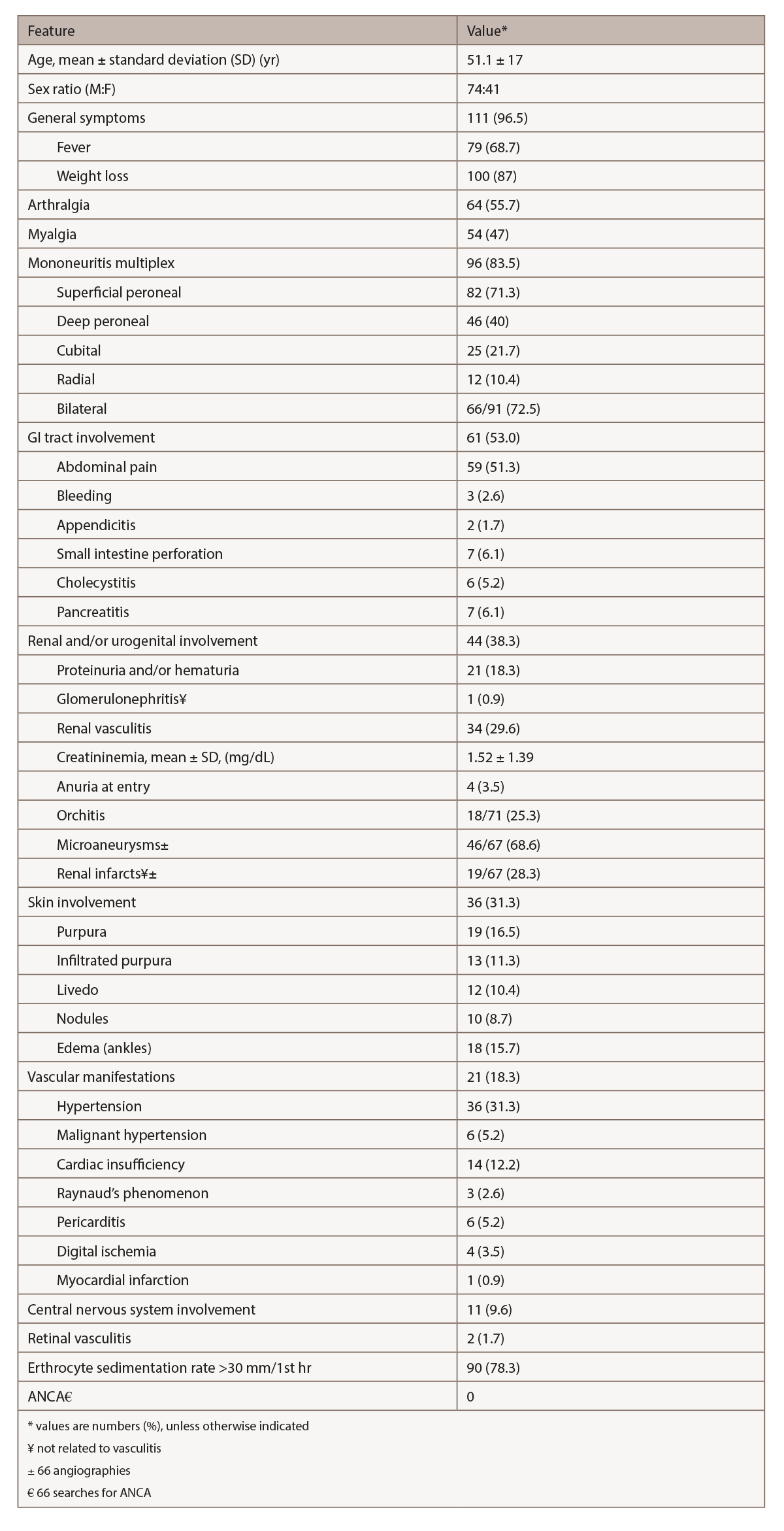

Clinical features of PAN encompass a wide constellation. Symptoms may be indolent, but life-threatening complications can occur. Constitutional symptoms, neurological manifestations and skin involvement are the most common findings.3 Table 2 (opposite) highlights the clinical symptoms in a retrospective study by Guillevin et al. of 115 patients with HBV-associated PAN.4 Unspecific constitutional symptoms include malaise, weight loss, fever, arthralgia and myalgia.2 Half of patients suffer myalgias, which may be intense, diffuse and occur spontaneously or after applying pressure.1 Arthralgias can predominantly affect the knees, ankles, elbows and wrists. Peripheral neuropathy, frequently manifested as mononeuritis multiplex, is a common finding in PAN.2 The preferentially involved nerves include the superficial peroneal, sural, radial, cubital and median.1 (Our patient had sural and median nerve involvement in an asymmetric and distal distribution.) Skin involvement includes purpura, livedoid lesions, subcutaneous nodules and necrotic ulcers.2 The most common cutaneous finding is palpable purpura, often necrotic and corresponding to subcutaneous small-vessel vasculitis.1 Our patient did not have any cutaneous manifestation.

Renal involvement consists of tissue infarction or hematoma. The hematoma is usually produced by the rupture of renal microaneurysms.2 Kidney infarcts may be clinically silent or produce micro- or macrohematuria, and mild to moderate proteinuria. Pagnoux et al. noted that peripheral neuropathy, recent onset hypertension (resulting from intrarenal artery involvement), skin nodules, orchitis and gastrointestinal manifestations were more frequent in patients with HBV-associated PAN than in patients with non-HBV-associated PAN.3

The time frame from HBV infection to PAN development is variable but generally occurs soon after infection. The Guillevin et al. study noted most patients became infected with HBV during the year preceding PAN and late occurrences are rare.4 Our patient’s HBV serologies indicated recent active infection and replication.

The usual response to HBV infection is the development of jaundice, preceded by systemic manifestations such as arthralgia, urticaria, migraines and a dramatic increase in transaminases.4 This constitutes the normal immune reaction to clear the virus.4 PAN seems to exacerbate the prodromal phase, and transaminase levels are only moderately elevated.4 Thus, PAN may delay or suppress the usual manifestation of acute HBV infection, as was noted in our patient.

In acute hepatitis, virus replication stops after a few weeks, when antibodies appear. Antibody production is first directed against HBeAg and then against HBsAg.4 This constitutes seroconversion. As noted by Guillevin et al., seroconversion is low in PAN.4 This suggests that in HBV-infected patients who develop PAN, active viral replication continues for a longer period than in HBV patients without PAN. We saw this in the HBV serologies obtained from our patient. This also forms the rationale for HBV-associated PAN utilizing antiviral therapy as the cornerstone of treatment, as opposed to non-infectious PAN in which immunosuppressive agents are utilized.

There are no specific lab tests to diagnose PAN. ESR and CRP are commonly elevated. Chronic anemia and leukocytosis frequently occur.2 Eosinophilia is occasionally present, which should prompt an evaluation for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Viral hepatitis serologies should be systematically sought.1 Hepatitis is frequent, but usually mild, and sometimes can be asymptomatic and thus misdiagnosed.4 Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) tests are typically negative in PAN. In the Guillevin et al. study, ANCA was not detected in 72 patients tested.4 In this same study, cryoglobulins were found in four of those 72 patients (5.6%) and monoclonal gammopathy in two patients (neither developed myeloma or Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia). AST and ALT levels were normal in 38 (33%) and 30 (26%) patients, respectively.4

(click for larger image) Table 2: Relevant Clinical & Laboratory Features in 115 Patients with HBV-PAN4

Biopsy is crucial to confirm the diagnosis of vasculitis and exclude other disorders. To achieve the maximum diagnostic yield, biopsy must be directed to symptomatic sites (i.e., muscle, sural nerve, skin or testicle).2 In the Pagnoux et al. study of 384 patients with PAN, combined muscle and nerve biopsies in symptomatic patients provided histological confirmation of vasculitis in 83%, whereas isolated muscle biopsies demonstrated vascular inflammation in 65%.2,3 When biopsies of muscle or nerve are blindly performed, vasculitis appears in up to one-third.2

Because renal involvement results from ischemia and the risk of hematoma from microaneurysm rupture exists, kidney biopsy is not recommended.1 Muscle biopsy should be performed at the site of myalgias or in the gastrocnemius or peroneal muscles.1 The diagnostic sensitivity of biopsies of proximal muscles (deltoid or quadriceps) is lower than those performed in distal muscles.1 A deep skin biopsy can show medium-size vessel involvement in patients with infiltrated necrotic purpura.1

The histological hallmark of PAN is focal segmental necrotizing vasculitis of medium-size arteries, less commonly arterioles, and only rarely capillaries and venules.1 The characteristic histological feature is the coexistence of necrotizing vasculitis and a healed lesion or normal arteries in different tissues or different parts of the same tissue.1 The acute phase of arterial wall inflammation is characterized by fibrinoid necrosis of the media and intense pleomorphic cellular infiltration, with neutrophils and variable numbers of lymphocytes and eosinophils.1

Angiography can help in visualizing microaneurysms and stenosis in medium-size arteries.1 Typical arteriographic lesions in PAN are arterial saccular or fusiform microaneurysms (1–5 mm in diameter), usually coexisting with stenotic lesions and predominantly in kidney, mesenteric and hepatic artery branches.2 An argument can be made that when characteristic angiographic lesions are detected in the appropriate clinical context, the diagnosis of PAN can be made even in the absence of histological confirmation.2

Our case was atypical: No characteristic PAN lesions were visible on angiography. Aside from mononeuritis multiplex, the patient did not demonstrate any other manifestation of systemic vasculitis. Thus, we pursued sural nerve biopsy.

Recommendation: When evaluating a potential PAN case, obtain both angiography and a biopsy of an involved site (if possible) to maximize the diagnostic yield.

The original ACR-proposed classification criteria for PAN in 1990 had important limitations. It did not consider microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) as a separate entity, and did not take ANCA testing into consideration.2 The 1994 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference did differentiate PAN from MPA, and the negativity of ANCA in PAN was emphasized in the updated 2012 Chapel Hill consensus definitions.2

Therapy

Treatment for HBV-associated PAN comprises a strategy that combines the clearance of immune complexes and suppression of HBV replication. In these cases, corticosteroids are usually begun to control potentially life-threatening organ damage from vasculitis.4 However, corticosteroids should be administered only for a short period to not prolong immune suppression in the face of HBV replication.

For life-threatening cases, plasma exchange may be useful, in addition to the use of antiviral agents. Plasma exchange removes the immune complexes, which are the major determinant of vessel inflammation. The frequency and number of plasma exchange sessions can be individualized for each case.

The antiviral agent targets the source of immune complex development by diminishing the viral load, eventually stopping viral replication and facilitating seroconversion.

This strategy of combining plasma exchange and antiviral therapy has been borne out in studies conducted by the French Vasculitis Study Group. The seroconversion rate is significantly higher in HBV-PAN patients given the antiviral strategy than in those treated with immunosuppressants, and those receiving the latter regimens had higher probabilities of relapsing.4 The benefits of the antiviral strategy also continue for the long term, lowering the risk of cirrhosis and carcinoma.

Conclusion

Hepatitis B-associated PAN is now rare, given the recent advances in HBV vaccination and antiviral therapies. PAN is a systemic necrotizing vasculitis that primarily affects medium-size arteries. Clinical presentation includes constitutional symptoms, neurological manifestations such as mononeuritis multiplex, and cutaneous involvement. Diagnosis encompasses checking hepatitis B serologies, inflammatory markers, angiography and biopsy of an involved site. Treatment includes a brief course of corticosteroids along with plasma exchange and antiviral therapy.

Naveen Raj, DO, is a rheumatologist and clinical associate professor of medicine at the University of Tennessee Medical Center, Knoxville, Tenn.

Naveen Raj, DO, is a rheumatologist and clinical associate professor of medicine at the University of Tennessee Medical Center, Knoxville, Tenn.

Lisa Duncan, MD, is an associate professor and chair of the pathology department at the University of Tennessee Medical Center, Knoxville, Tenn.

Lisa Duncan, MD, is an associate professor and chair of the pathology department at the University of Tennessee Medical Center, Knoxville, Tenn.

References

- Guillevin L, Terrier B. (2014) Oxford Textbook of Vasculitis. New York, Oxford University Press.

- Hernandez-Rodriguez J, Alba M, Prieto-Gonzalez S, et al. Diagnosis and classification of polyarteritis nodosa. J Autoimmun. 2014 Feb–Mar;48–49:84–89.

- Pagnoux C, Seror R, Henegar C, et al. Clinical features and outcomes in 348 patients with polyarteritis nodosa: A systematic retrospective study of patients diagnosed between 1963 and 2005 and entered into the French Vasculitis Study Group Database. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Feb;62(2):616–626.

- Guillevin Loic, Mahr A, Callard P, et al. Hepatitis B virus associated polyarteritis nodosa: Clinical characteristics, outcomes, and impact of treatment in 115 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2005 Sep;84(5):313–322.