Shrinking lung syndrome (SLS) is a rare cause of dyspnea that has been most commonly described in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), but is also found in systemic sclerosis, Sjögren’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Shrinking lung syndrome is characterized by a restrictive pattern on lung spirometry, despite normal lung parenchyma, and an elevated diaphragm.1 We report a case of shrinking lung syndrome that was part of the initial presentation of SLE. Diaphragmatic ultrasound helped confirm the diagnosis by directly visualizing diaphragm dysfunction and aided rapid diagnosis.

Shrinking lung syndrome (SLS) is a rare cause of dyspnea that has been most commonly described in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), but is also found in systemic sclerosis, Sjögren’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Shrinking lung syndrome is characterized by a restrictive pattern on lung spirometry, despite normal lung parenchyma, and an elevated diaphragm.1 We report a case of shrinking lung syndrome that was part of the initial presentation of SLE. Diaphragmatic ultrasound helped confirm the diagnosis by directly visualizing diaphragm dysfunction and aided rapid diagnosis.

Case Presentation

A 25-year-old woman without a significant past medical history presented to the emergency department with cough associated with dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, fever, an eight-month history of arthralgias, joint stiffness and myalgia. She had received a course of doxycycline as an outpatient, but with only minimal improvement in her symptoms. Family history was notable for two cousins with SLE. Her physical exam revealed tenderness at her metacarpophalangeal joint, wrists and shoulders bilaterally, and a question of joint effusions in her knees.

She was found to have an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 73 mm/hr (reference range [RR]: 0–15 mm/hr), white blood cell count of 2.8 x103/mcL (RR: 4–11 x103/mcL) and hemoglobin of 11.3 g/dL (RR: 11.7–16.0 g/dL). Anti-nuclear antibody titers were high (1:1,280) with low titer-positive scleroderma antibody (Scl-70) of 269.5U and anti-double-stranded DNA antibody of 75.4 IU/mL (RR: 0–75 IU/mL). She had no autoantibodies or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies. Her rheumatoid factor, complement levels and creatine kinase were within normal limits.

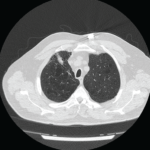

A chest X-ray was notable for low lung volumes. A computed tomography (CT) chest scan showed lower lobe infiltrates in both lungs and a small, right-side pleural effusion.

Given the concern for pneumonia, the patient was started on ceftriaxone. With concern for SLE as the cause of this clinical presentation, antibiotics were discontinued in favor of high-dose corticosteroids.

One month later, the patient was seen in follow-up and reported improved arthralgias and myalgias, but she continued to be dyspneic and developed ambulatory hypoxemia. She was sent for urgent CT angiography of the chest, which showed no evidence of pulmonary embolism and only minimal lower lobe atelectasis with small right pleural effusion. Transthoracic echocardiogram was unremarkable. The etiology of her dyspnea remained unclear, and the patient was initiated on hydroxychloroquine and tapered off corticosteroids given the improvement in arthralgias.

Two months later, pulmonary function testing (PFTs) showed forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) of 24%; forced vital capacity (FVC) of 26%, for a ratio 0.93; total lung capacity (TLC) of 33%; and diffusing lung capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) of 19%. Clinical suspicion was for shrinking lung syndrome given the lack of prior lung infiltrates and hypoinflated lungs.