Shrinking lung syndrome (SLS) is a rare cause of dyspnea that has been most commonly described in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), but is also found in systemic sclerosis, Sjögren’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Shrinking lung syndrome is characterized by a restrictive pattern on lung spirometry, despite normal lung parenchyma, and an elevated diaphragm.1 We report a case of shrinking lung syndrome that was part of the initial presentation of SLE. Diaphragmatic ultrasound helped confirm the diagnosis by directly visualizing diaphragm dysfunction and aided rapid diagnosis.

Shrinking lung syndrome (SLS) is a rare cause of dyspnea that has been most commonly described in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), but is also found in systemic sclerosis, Sjögren’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Shrinking lung syndrome is characterized by a restrictive pattern on lung spirometry, despite normal lung parenchyma, and an elevated diaphragm.1 We report a case of shrinking lung syndrome that was part of the initial presentation of SLE. Diaphragmatic ultrasound helped confirm the diagnosis by directly visualizing diaphragm dysfunction and aided rapid diagnosis.

Case Presentation

A 25-year-old woman without a significant past medical history presented to the emergency department with cough associated with dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, fever, an eight-month history of arthralgias, joint stiffness and myalgia. She had received a course of doxycycline as an outpatient, but with only minimal improvement in her symptoms. Family history was notable for two cousins with SLE. Her physical exam revealed tenderness at her metacarpophalangeal joint, wrists and shoulders bilaterally, and a question of joint effusions in her knees.

She was found to have an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 73 mm/hr (reference range [RR]: 0–15 mm/hr), white blood cell count of 2.8 x103/mcL (RR: 4–11 x103/mcL) and hemoglobin of 11.3 g/dL (RR: 11.7–16.0 g/dL). Anti-nuclear antibody titers were high (1:1,280) with low titer-positive scleroderma antibody (Scl-70) of 269.5U and anti-double-stranded DNA antibody of 75.4 IU/mL (RR: 0–75 IU/mL). She had no autoantibodies or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies. Her rheumatoid factor, complement levels and creatine kinase were within normal limits.

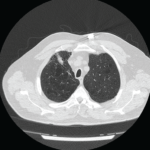

A chest X-ray was notable for low lung volumes. A computed tomography (CT) chest scan showed lower lobe infiltrates in both lungs and a small, right-side pleural effusion.

Given the concern for pneumonia, the patient was started on ceftriaxone. With concern for SLE as the cause of this clinical presentation, antibiotics were discontinued in favor of high-dose corticosteroids.

One month later, the patient was seen in follow-up and reported improved arthralgias and myalgias, but she continued to be dyspneic and developed ambulatory hypoxemia. She was sent for urgent CT angiography of the chest, which showed no evidence of pulmonary embolism and only minimal lower lobe atelectasis with small right pleural effusion. Transthoracic echocardiogram was unremarkable. The etiology of her dyspnea remained unclear, and the patient was initiated on hydroxychloroquine and tapered off corticosteroids given the improvement in arthralgias.

Two months later, pulmonary function testing (PFTs) showed forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) of 24%; forced vital capacity (FVC) of 26%, for a ratio 0.93; total lung capacity (TLC) of 33%; and diffusing lung capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) of 19%. Clinical suspicion was for shrinking lung syndrome given the lack of prior lung infiltrates and hypoinflated lungs.

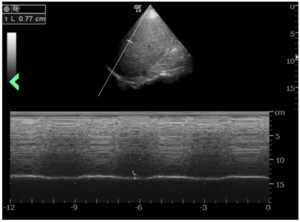

The patient was referred to a pulmonary specialist, who performed diaphragmatic ultrasound. The ultrasound revealed both reduction in diaphragm dome excursion and in diaphragm thickening fraction, consistent with bilateral diaphragm dysfunction, confirming diaphragmatic dysfunction and a diagnosis of shrinking lung syndrome (see Figure 1). Follow-up high-resolution CT showed no evidence of interstitial lung disease. Mycophenolate mofetil was initiated, in addition to prednisone.

Figure 1: The ultrasound revealed a reduction in diaphragm dome excursion of 0.77 cm (normal value for deep inspiration: 4.8 cm) and in diaphragm thickening fraction, consistent with bilateral diaphragm dysfunction. (Click to enlarge.)

Repeat PFTs three months later demonstrated improvement, with FVC post 39%, FEV1 post 37%, FEV1/FVC post 92% predicted, TLC 50%, DLCO 38%, reduction in mean inspiratory pressure and decline of vital capacity from a seated to supine position.

Discussion

Diagnosis of shrinking lung syndrome usually follows the diagnosis of SLE, with a mean interval of 66.7 months.2 This case is atypical because shrinking lung syndrome was part of the initial presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus. This added to diagnostic uncertainty in this case.

It is important to highlight the role of ultrasonography of the diaphragm in our case, which confirmed diaphragm involvement and assisted us in making the diagnosis of shrinking lung syndrome. Upon our patient’s initial presentation to the hospital, there was concern for a possible overlying acute process, such as neumonia. Although additional CT scans showed resolution of parenchymal lung abnormalities, the patient continued to have severe dyspnea. Subsequent PFTs showed restrictive lung defect and resulted in an unclear clinical picture.

Fortunately, ultrasonography is a noninvasive and rapid bedside test that can provide real-time data on diaphragmatic function without subjecting patients to radiation. It has a sensitivity and specificity of more than 90% for diagnosis of diaphragmatic dysfunction.3-5 Real-time ultrasound in this case confirmed diaphragmatic dysfunction and enabled immediate initiation of immunosuppressive therapy, rather than waiting for repeat chest imaging.

Although the exact pathogenesis of shrinking lung syndrome is unclear, several hypotheses have been proposed, including that it may result from surfactant deficiency, isolated diaphragmatic myopathy, phrenic neuropathy, chest wall dysfunction or pleural adhesions.6

Recent data suggest that shrinking lung syndrome may be a complication of pleural inflammation. Inflammation, particularly around the regions of the diaphragmatic pleura or a pleural region near the diaphragm, could lead to chronic lung hypoinflation and loss of compliance due to activation of local neuroreflexes, which inhibit diaphragm function and eventually cause diaphragmatic remodeling.7

In addition to volitional control, diaphragmatic function is regulated by neuronal reflex arcs. Pleuralphrenic reflex arcs, activated by pleural afferents, lead to phrenic nerve inhibition. These arcs can be activated by pleural inflammation and thereby inhibit deep inspiration, resulting in chronic lung hypoinflation and decreased compliance.2-6 Similarly, pain-induced inactivation of the diaphragm may also play a role in diaphragm dysfunction in patients with shrinking lung syndrome.8

This case supports the theory that shrinking lung syndrome may arise as a complication of pleuritis because our patient had evidence both of pleural inflammation on CT scan and clear diaphragmatic dysfunction. No evidence supported structural causes of extrinsic restriction, such as chest wall deformities or pleural adhesions. No evidence of systemic myopathy was found given normal creatine kinase, and no other clinical features suggested myositis. Phrenic nerve stimulation tests were not attempted. Notably, Laroche et al. showed that a high proportion of SLE patients with shrinking lung syndrome had normal or approximately normal diaphragm contractility, suggesting that normal contractility is not enough to rule out a diagnosis of shrinking lung syndrome.9 Interestingly, even after resolution of all pleural inflammation and normalization of inflammatory markers, diaphragm dysfunction remained.

No evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of shrinking lung syndrome currently exist. Most commonly, patients are initially treated with corticosteroids. Adjunctive treatments include inhaled beta-2 agonists, theophylline, analgesia and chest physiotherapy. In steroid-refractory cases, additional immunosuppressants, such as azathioprine and cyclophosphamide, are used. Unfortunately, randomized clinical trials have not yet been undertaken to provide data regarding comparative efficacy. More recently, isolated case reports have documented a potential role rituximab, with or without cyclophosphamide.10-13

Overall prognosis for shrinking lung syndrome is variable. Most patients have improvement and stabilization of PFTs, and very few require supplemental oxygen. However, restrictive lung defects seen on PFTs rarely return to normal.6

In this case, in addition to PFTs, diaphragmatic ultrasound allowed monitoring of treatment response with a 50% improvement in diaphragm thickening after therapy with improving airflows.3 Despite the concerning clinical presentation and poor response to conventional therapy, it is thought that the low mortality rates of patients with shrinking lung syndrome may be secondary to the patient’s preserved ventilatory drive limiting further progression of respiratory deterioration, given the inflammatory process hypothetically causes a primarily functional process.7 However, this may also contribute to delayed diagnosis.

So far, our patient seems to match the typical progression of shrinking lung syndrome. Although her lung function has improved, she continues to have significant restrictive lung dysfunction.

In Sum

Shrinking lung syndrome continues to be under-recognized overall, although awareness of the condition has increased over the past few years. Contrary to popular belief, shrinking lung syndrome could be an early feature of SLE. We should keep a high index of suspicion among patients with connective tissue disease who present with dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain and elevation of the diaphragm.

Although PFTs and chest CT remain essential to the diagnosis, diaphragm ultrasound can help confirm diaphragmatic dysfunction and supports a shrinking lung syndrome diagnosis, particularly in challenging cases. Given the potential for chronic restrictive lung physiology, early diagnosis may minimize long-term respiratory dysfunction.

Mery Deeb, MD, is a resident in internal medicine at the Department of Medicine, Brown University, Providence, R.I., and Kent Hospital, Warwick, R.I.

Taro Minami, MD, is with the Department of Medicine, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, R.I.

Michael Stanchina, MD, is with the Department of Medicine, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and the Division of Pulmonary/Critical Care Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and Care New England Hospitals, Rhode Island.

Elias Jabbour, MD, is with the Division of Pulmonary/Critical Care Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and Care New England Hospitals, Rhode Island.

Jan Karczewski, MD, is with the Division of Rheumatology, Kent Hospital, Warwick, R.I.

Disclosures

Dr. Minami served as a consultant for Fujifilm (until 2023) and AA Health Dynamics (until January 2024) to teach point-of-care ultrasound in Kenya, a project funded by Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry.

References

- Hoffbrand BI, Beck ER. ‘Unexplained’ dyspnoea and shrinking lungs in systemic lupus erythematosus. Br Med J. 1965 May 15;1(5445):1273–1277.

- Hoffman BJ. Sensitivity to sulfadiazine resembling acute disseminated lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1945;51(3):190–192.

- Minami T, Manzoor K, McCool FD. Assessing diaphragm function in chest wall and neuromuscular diseases. Clin Chest Med. 2018 Jun;39(2):335–344.

- McCool FD, Tzelepis GE. Dysfunction of the diaphragm. N Engl J Med. 2012 Mar 8;366(10):932–942.

- Yamada T, Minami T, Yoshino S, et al. Diaphragm ultrasonography: Reference values and influencing factors for thickness, thickening fraction, and excursion in the seated position. Lung. 2024 Feb;202(1):83–90.

- Borrell H, Narváez J, Alegre JJ, et al. Shrinking lung syndrome in systemic lupus erythematosus: A case series and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Aug;95(33):e4626.

- Henderson LA, Loring SH, Gill RR, et al. Shrinking lung syndrome as a manifestation of pleuritis: A new model based on pulmonary physiological studies. J Rheumatol. 2013 Mar;40(3):273–281.

- Hawkins P, Davison AG, Dasgupta B, et al. Diaphragm strength in acute systemic lupus erythematosus in a patient with paradoxical abdominal motion and reduced lung volumes. Thorax. 2001 Apr;56(4):329–330.

- Laroche CM, Mulvey DA, Hawkins PN, et al. Diaphragm strength in the shrinking lung syndrome of systemic lupus erythematosus. Q J Med. 1989 May;71(265):429–439.

- DeCoste C, Mateos-Corral D, Lang B. Shrinking lung syndrome treated with rituximab in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus: A case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2021 Jan 6;19(1):7.

- Goswami RP, Mondal S, Lahiri D, et al. Shrinking lung syndrome in systemic lupus erythematosus successfully treated with rituximab. QJM. 2016 Sep;109(9):617–618.

- Langenskiöld E, Bonetti A, Fitting JW, et al. Shrinking lung syndrome successfully treated with rituximab and cyclophosphamide. Respiration. 2012;84(2):144–149.

- Peñacoba Toribio P, Córica Albani ME, Mayos Pérez M, Rodríguez de la Serna A. Rituximab in the treatment of shrinking lung syndrome in systemic lupus erythematosus. Reumatol Clin. 2014 Sep-Oct;10(5):325–327.