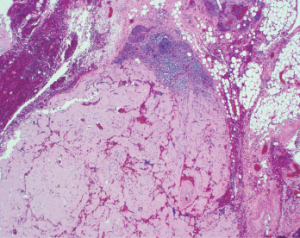

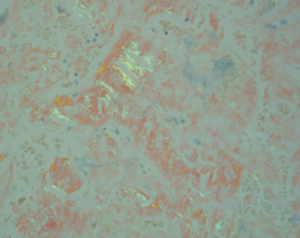

Figure 1

This image shows a lymph node with near-total replacement by amorphous amyloid material (H&E, 100x).

A 54-year-old African American man arrived at the emergency department with the acute onset of a tender mass on the left side of his neck. It had been getting progressively larger for the preceding two days.

History & Examination

His history included chronic right hip osteoarthritis with two surgeries performed five years prior. At his initial presentation, he noted increased fatigue the preceding few days, as well as generalized weakness and decreased appetite.

His habits included smoking a half-pack of cigarettes daily for 30 years, occasional alcohol consumption and avoidance of recreational substances. Because he had been employed by the oil industry working on scaffolding, he had traveled extensively throughout the U.S. for work, but he denied traveling outside the country or to regions where Lyme disease is known to be endemic.

On examination, he displayed a 4–5 cm non-pulsatile mass on the left side of his neck. It was moderately tender to palpation. He also had mild thyromegaly with a suggestion of thyroid nodules. His right hip was not tender and had no swelling, ecchymosis, warmth or erythema. Flexion of his hip was limited to 90º, and internal as well as external rotation was limited to approximately 15º.

Evaluation of laboratory tests revealed an elevated rheumatoid factor at 25 (upper limit of normal [ULN]: 14), and an elevated serum immunoglobulin G at 1,700 mg/dL (ULN: 1,600 mg/dL). Serum protein electrophoresis revealed a total gamma component elevation at 1.74 g/dL (ULN: 1.6 g/dL) with M-component elevation at 1.28 g/dL (ULN: 0 g/dL).

Dr. Bhavasar

A computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast of the patient’s neck revealed a large, mildly heterogeneous inferior left neck and left subclavicular mass, likely reflecting a large nodal conglomerate approximately 4.5 cm anteroposterior, 7.5 cm transverse and 7.5 cm in cranio-caudal dimensions. Portions were hypoattenuating relative to muscle, perhaps reflecting cystic or necrotic areas. Calcifications seen within the mass, in conjunction with an enlarged multinodular thyroid gland, were most worrisome for metastatic lymphadenopathy related to thyroid cancer. An X-ray of his right hip displayed total arthroplasty without evidence of acute complication.

Fine needle aspiration of the thyroid nodule noted on the CT scan was performed and found to be consistent with a lymphocytic (Hashimoto) thyroiditis. The neck mass was biopsied, and subsequent tissue studies revealed a Gram stain with very few white blood cells, no organisms and no acid-fast bacilli. A tissue culture did not result in growth of bacteria, yeast, fungi or mycobacteria at six weeks. The biopsy demonstrated lymph nodes and fibro-adipose tissue with extensive replacement by amorphous deposits of acellular material consistent with amyloid (see Figure 1, above right). A Congo red stain was positive for polarized apple-green birefringent material, confirming the impression of amyloid (see Figure 2, p. 38). Amyloid also involved vessel walls, and areas of ossification were present. The biopsy material subsequently underwent liquid chromatography tandem mass spectroscopy at Mayo Clinic Laboratories, which subtyped the amyloid as AL (lambda) type.

Dr. Joste

A follow-up positron emission tomography (PET) scan demonstrated persistence of the left neck mass and an unexpected retroperitoneal area of involvement. A bone marrow biopsy revealed normal cellular trilineage hematopoiesis, and flow cytometry showed a lambda-restricted plasma cell population by CD138 immunostain estimated to be 5–9% plasma cells consistent with AL-type amyloid, although no overt evidence of amyloid was observed in the bone marrow.

Our patient was diagnosed with an unusual nodular AL amyloid with two areas of involvement (including his left neck and a retroperitoneal area) without a predisposing systemic autoimmune or rheumatologic condition.

Following the amyloidosis diagnosis, the patient was evaluated by a hematologist and an oncologist, who devised a treatment plan consisting of the administration of subcutaneous bortezomib along with dexamethasone on a weekly basis three of four weeks each month.

A transthoracic echocardiogram performed to assess possible cardiac involvement revealed a mild reduction of left ventricular systolic function with a calculated ejection fraction of 49%, as well as a transmitral spectral Doppler flow pattern suggestive of mild diastolic dysfunction, with normal left ventricular end diastolic pressure and mild global hypokinesis of the left ventricle. At press time, the patient had yet to obtain further cardiac evaluation regarding these findings.

Given the paucity of data regarding management of such an uncommon presentation of amyloidosis, expertise from specialists at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., was sought. The hematologist and oncologist believed the patient may be a candidate for an autologous stem cell transplant in the future.

The patient’s right hip osteoarthritis, with prior hip replacement with revision surgery, was most likely mechanical in origin, stemming from prior physical activity rather than an underlying systemic disease. For this, we recommended he continue conservative management using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and pursue activity only as tolerated.

Finally, the thyroid nodule initially noted on the CT scan and subsequently determined on fine needle aspiration to be consistent with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis was determined to be best monitored by the endocrinology service.

Discussion

Figure 2. This image shows fibrous tissue with apple-green birefringent material consistent with the presence of amyloid (H&E, 400x).

Amyloidosis is a condition consisting of several distinct clinical entities sharing the common pathological feature of protein misfolding, resulting in fibrils consisting of a highly structured, stable, beta-sheet confirmation prone to binding with other like molecules. Upon visualization of amyloid tissue stained Congo red under polarized microscopy, one can appreciate a highly characteristic apple-green birefringence appearance.

Although the most common forms include AL (primary) and AA (secondary) amyloidosis, other forms include dialysis-associated, age-related, heritable forms and organ-specific amyloid with multiple deposits. The secondary AA form often appears with several rheumatologic conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, chronic juvenile polyarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, dermatomyositis, systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis and Sjögren’s syndrome, in addition to a number of chronic inflammatory conditions, including inflammatory bowel disease, familial periodic fever syndromes, chronic infections and certain neoplasms.1

Although the systemic form is seen most often and localized presentations occur less frequently, organ-specific deposits may also be observed, such as Alzheimer’s disease deposition in the aging brain or type 2 diabetes deposits in the islets of Langerhans.2 Somewhat less commonly encountered organ-specific deposits include isolated bladder amyloidosis, in addition to localized hepatic forms.

In contrast, localized AL amyloid appears much less frequently and may present as a localized tumor-like nodule or a collection of several nodules. Symptoms vary due to the location of presentation or the structures affected. With such localized presentations, the specter of malignancy is often lurking, particularly when the breast, lung and urinary tract are involved. The most frequently encountered sites of localized AL amyloid deposition include the eyelids, skin, bronchi, larynx and urinary tract.2

In our case, the presentation of localized AL amyloid in the neck was found to involve several structures, including blood vessels, a lymph node and subcutaneous tissue. Additionally, the calcifications visualized on CT imaging were highly suspicious for cancer, particularly given the context of a noted hyper-functioning thyroid nodule; metastatic lymphadenopathy from a primary thyroid malignancy was of legitimate concern. Calcifications commonly appear in nodular presentations of AL amyloid, and microcalcifications are often identified when breast tissue is involved. When such microcalcifications appear on mammography, concern for cancer is heightened.2

Amyloidosis is a condition consisting of several distinct clinical entities sharing the common pathological feature of protein misfolding, resulting in fibrils consisting of a highly structured, stable, beta-sheet confirmation prone to binding with other like molecules.

Within the scope of rheumatology, three distinct conditions come to mind when considering neck masses, per a study performed by Knopf et al.: 1) Sjögren’s syndrome, where neck involvement is typical; 2) granulomatous with polyangiitis, in which upper airway and sinonasal manifestations often precede systemic manifestations; and 3) sarcoidosis, in which pulmonary manifestations dominate, although isolated head and neck presentations may appear.3

In the study, head and neck symptoms suggestive of Sjögren’s included sicca and salivary gland enlargement, followed by lymphadenopathy and facial swelling.3 Patients diagnosed with granulomatosis with polyangiitis experienced a broad spectrum of head and neck symptoms, the majority being sinonasal tract and middle ear related, including rhinorrhea, facial and cranial pain, otorrhea, dyspnea and dysphonia, recurrent epistaxis and diploplia.3 Sarcoidosis head and neck symptoms included lymphadenopathy, salivary gland enlargement, sicca, facial and cranial pain, rhinorrhea and facial palsy.

Of course, both infectious and neoplastic conditions remain high on the differential with any of the above presenting symptomatology.3

The time course of presentation (i.e., acute, subacute, chronic) of a neck mass may hold substantial bearing on determining etiology. Typically, neck masses seen in an acute presentation tend to be symptomatic, with the most common causes of cervical lymphadenopathy being attributable to infection or inflammation created by a wide variety of odontogenic, salivary, viral and bacterial etiologies.4 These lymph nodes are often tender, swollen and mobile, and can be erythematous and warm to the touch.

In our case, although the presentation was described as acute (appearing over the span of one to two days), it was an unusual time course for the given etiology of amyloidosis, which has more typically been encountered as a subacute presentation over a period of several weeks to months. Subacute masses are classified as occurring within weeks to months, and although they may grow fairly quickly, they often go unnoticed at onset due to their asymptomatic nature.4

Persistent asymptomatic neck masses in an adult should, in general, be considered malignant until proven otherwise.4 This certainly was of prime concern for us, regardless of the duration of our patient’s neck mass. Note: Biopsy is appropriate if an abnormal lymph node has not resolved after four to six weeks, and it should be performed promptly in patients with other findings suggestive of malignancy, such as night sweats, fever, weight loss or a rapidly growing mass.4

In subacute neck masses, amyloidosis falls under less commonly encountered etiologies, alongside lymphoma, metastatic cancers, parotid tumors, sarcoidosis and Sjögren’s, while the most common causes include metastatic squamous cell carcinomas of the aerodigestive tract.4 Rarely encountered subacute masses are most often the result of Castleman disease, Kikuchi disease, Kimura disease and Rosai-Dorfman disease.4

The initial diagnostic test of choice in an adult with a persistent neck mass is contrast-enhanced CT, which provides valuable initial information regarding the size, extent, location and content or consistency of the mass.5 Additionally, contrast media may help identify malignant lymph nodes that are not enlarged, and distinguish vessels from lymph nodes.5 Avoid iodine-based contrast media in patients with a history of thyroid disease or when metastatic thyroid cancer is a concern.5

Although PET-CT can be used to distinguish between malignant and unaffected tissues, its use in preliminary diagnosis is not as effective and should be limited to managing a malignancy.5 Ultrasonography may also help guide fine needle aspiration of non-palpable or small superficial lesions.5 Although CT and ultrasonography share similar capabilities, ultrasonography is preferred initially in young patient populations to reduce radiation exposure. It may also be preferred to avoid contrast media-induced nephropathy in patients with underlying renal disease.

CT angiography is recommended for evaluating a pulsatile neck mass and is preferred over magnetic resonance angiography.5 The clinician may proceed with fine needle aspiration (if indicated) once appropriate imaging has ruled out involvement of underlying vital structures.5 Fine needle aspiration can provide further information through cytology, flow cytometry, Gram stain, and bacterial and acid-fast bacilli cultures while avoiding complications of open biopsy.4

Persistent asymptomatic neck masses in an adult should, in general, be considered malignant until proven otherwise.

Final Thoughts

In conclusion, our case demonstrated a relatively rare presentation of amyloidosis as a localized neck mass with additional localization to the peritoneum discovered through a PET scan and confirmed by systemic elevation of monoclonal immunoglobulin fragments.

The teaching points raised in this case include the various presentations of amyloidosis, the variety of rheumatologic causes of neck masses, the nature and presentation of neck masses in general and the methods of evaluating a neck mass.

Tej Bhavsar, MD, is a recent graduate and former chief fellow of the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque. He is a practicing rheumatologist with the Center for Rheumatology based in Albany, N.Y., and sees patients in Saratoga Springs, N.Y.

Nancy Joste, MD, is director of anatomic pathology and a professor in the pathology department at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Mary Barry, MD, for diagnostic assistance.

References

- Dhillon V, Woo P, Isenberg D. Amyloidosis in the rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989 Aug;48(8):696–701.

- Westermark P. Localized AL amyloidosis: A suicidal neoplasm? Ups J Med Sci. 2012 May;117(2):244–250.

- Knopf A, Bas M, Chaker A, et al. Rheumatic disorders affecting the head and neck: Underestimated diseases. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011 Nov;50(11):2029–2034.

- Haynes J, Arnold K, Aguire-Oskins C, et al. Evaluation of neck masses in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2015 May 15;91(10):698–706.

- Wippold FJ II, Cornelius RS, Berger KL, et al. Expert panel on neurologic imaging. American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria. 2012.