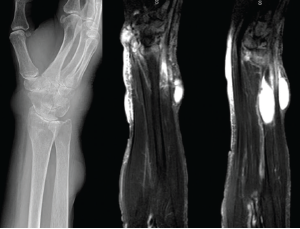

Figure 3: X-rays & MRI

The left panel shows an X-ray from admission of the upper right extremity, with notable discrete areas of soft tissue swelling, and radiocarpal joint space narrowing. The middle and right panels show MRI short tau wave inversion sequences, with several areas of mildly complex, enhancing subcutaneous cysts and associated soft tissue edema.

Numerous reports in the literature involve patients who were misdiagnosed with RA, gout or psoriatic arthritis and were only identified as having disseminated sporotrichosis after multiple treatment failures with systemic immunosuppression.6–9

The presentation of Sporothrix arthritis is often variable, with reports of monoarticular, oligoarticular and even polyarticular disease being common. Although skin findings are often present, they are frequently attributable to the suspected underlying disease process.6

There are also reports of misdiagnosis of Sporothrix arthritis with vasculitis, sarcoidosis and pyoderma gangrenosum, with confusion often owing to the presence of mixed granulomatous and suppurative inflammation on histology, often with no apparent fungal elements.10–14 In the majority of these cases, diagnosis was delayed by months despite attempts at biopsy or arthrocentesis, which initially failed to demonstrate the causative organism. The diagnosis was often made when cultures were repeated after patients failed to improve on systemic immunosuppression, likely due to increases in organism burden resulting in improved sensitivity of cultures and histologic examination.10–12

The development of large, painful nodules on exam was also suggestive of a diagnosis other than rheumatoid arthritis. As noted in our exam, these lesions were fluctuant to palpation and quite tender, suggestive of a fluid collection, such as a cyst or abscess. This contrasts with the typically firm, rubbery character of rheumatoid nodules.

Mycotic cysts or pseudocysts may also be mistaken for benign conditions, such as synovial cysts or epidermal inclusion cysts; however, these conditions are usually not associated with worsening inflammatory arthritis and are not typically painful.14

It is also worth emphasizing that although the classic description of sporotrichosis is of lymphocutaneous spread following direct inoculation by contaminated plant matter, other cutaneous and systemic findings can be seen, particularly in immunocompromised patients.15 Cutaneous infection may manifest as nodular or noduloulcerative lesions, ulcers, cysts, pseudocysts or verrucous papular lesions.16

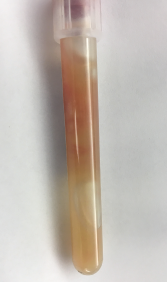

Figure 4

Gelatinous aspirate collected from subcutaneous nodules.

Our patient lacked an obvious history of gardening or rose exposure that would suggest the possibility of sporotrichosis, and yet this should not have excluded the possibility of infection, because a specific exposure is not identified in many cases.

Inoculation with Sporothrix species is classically tied to exposure to plant matter; however, there are also reports of animal-associated disease. In particular, feline-transmitted Sporothrix brasiliensis has been responsible for an epidemic of infections in Brazil.15,17 In osteoarticular infections, the organism may be directly introduced into a joint; however, it may also spread contiguously (as in from skin to joint) or by hematogenous route, in the case of pulmonary inoculation.15,17

Overall, this heterogeneity in possible mechanisms of inoculation creates a diagnostic challenge and illustrates the need for broad differential considerations in immunocompromised patients.

Arguably the most important clue for an infectious process in both our case and for many reported cases in the literature was a failure to respond to what should have been adequate immunosuppression for the treated condition. Although not an ideal long-term therapy, 20 mg of prednisone daily should have provided reasonable control for our patient’s RA.18,19 Her chronic prednisone use at a dose of 20 mg was also an important risk factor for serious infection, particularly with an opportunistic organism.20–23

Disseminated sporotrichosis appears to be more common in patients with compromised cellular immunity. This includes patients on immunosuppressive regimens, but also individuals with HIV/AIDS, diabetes or alcoholism.15

The treatment is generally a combination of amphotericin B and itraconazole, narrowing to itraconazole monotherapy after initial clinical improvement.15–17 The duration of treatment depends on the severity of infection and host immune factors, with long-term (six months to a year) therapy often necessary in immunocompromised patients.15–17