Figure 1: Salient Features of the Patient Exam

The top left panel shows synovitis in the right second through fourth metacarpal phalangeal joints, with large subcutaneous cysts involving the distal forearm and wrist. The top right panel shows a right forearm lesion with overlying ulceration. The bottom left panel demonstrates marked swelling in left ankle. The bottom right panel shows scattered ulcerations on the upper left arm.

A 61-year-old Caucasian woman with a history of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis (RA) was hospitalized for a several-month history of progressively worsening left ankle pain and swelling.

She had been unable to bear weight on her left leg for several days and did not notice improvement in symptoms with 20 mg of prednisone daily, which she had increased to 40 mg daily a few days prior to admission. Her right wrist and hand were also painful and swollen. Over the preceding months, she had noted progressively enlarging, painful nodules on her right forearm, one of which had spontaneously drained yellow-tinged fluid. She had also developed ulcerations over some of the nodules and the contralateral forearm. She did not have any preceding trauma to the right upper extremity. A review of systems was notable for several months of intermittent night sweats.

She had several pug dogs at home; one had recently died, and both had been experiencing rashes and skin issues. She reported no other pets, nor any unusual personal or occupational exposures.

The patient had been diagnosed with seropositive RA at age 55 and had been previously treated with multiple biologic and conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), most recently with good therapeutic response to rituximab.

Unfortunately, she had lost her private insurance coverage, resulting in poor access to care and being off all biologics for a year at the time of her presentation. However, she reported taking 20 mg of prednisone daily for the preceding four or five months.

Other pertinent medical history included a previous left ankle infection, which, per the patient, had been treated successfully with surgical washout and intravenous antibiotics the prior year.

After an initial work-up for an infectious etiology proved negative, a rheumatologist was consulted for treatment recommendations for a presumptive inflammatory arthritis flare with concern for rheumatoid nodules or, possibly, ganglion cysts involving the right upper extremity.

Further history and review of outside records confirmed the history of polymicrobial left ankle septic arthritis, with cultures at the time yielding coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium and Sporothrix schenckii. Outside records indicated she had completed her recommended course of antibiotics for the bacterial infections; however, her insurance had lapsed prior to completion of the recommended six-month course of antifungal treatment.

On exam, the patient was Cushingoid and chronically ill appearing, with normal vital signs. Her musculoskeletal exam was notable for synovitis in her right second through fifth metacarpophalangeal joints, as well as in her right wrist, right elbow and left ankle (see Figure 1). Her left ankle was warm and tender, with pain on both active and passive range of motion. She was also noted to have several tender, fluctuant, cystic lesions on the right forearm, as well as shallow ulcerations on both upper arms (see Figure 1).

Figure 2: Comparison of X-rays

X-rays from 2017 (left) are notable for preserved joint spaces with distal fibular fracture. The 2019 X-rays (right) show diffuse, soft tissue swelling, severe erosions and talar collapse.

Pertinent lab results at the time of admission included a peripheral leukocytosis of 16.4% (109/L), with 92% neutrophils, erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 25 mm/hr and C-reactive protein of 46.4 mg/L. Arthrocentesis of the left ankle yielded 11,550 nucleated cells (differential not performed) and 25,300 red cells, with a negative gram stain and crystal analysis.

Radiographs demonstrated erosive change of the tibiotalar joints with chronic periosteal reaction and extensive soft tissue swelling, which was significantly changed from X-rays done approximately 19 months earlier (see Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed severe erosive changes, with talar collapse, and complex tibiotalar and subtalar joint effusions, with tenosynovitis of medial flexor tendons and peroneal tendons.

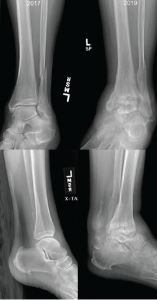

Disseminated sporotrichosis was suspected due to the pattern of destruction in her ankle, as well as the appearance of cutaneous cystic lesions. An MRI of the right forearm was obtained, which demonstrated multiple mildly complex subcutaneous and soft tissue fluid collections, as well as dorsal compartment tenosynovitis (see Figure 3).

The rheumatology team recommended consultation with an orthopedist, who reviewed the imaging and felt the findings were more likely related to sequelae of advanced rheumatoid arthritis than to an atypical infection.

Given the concern for possible disseminated fungal infection and the uncertain etiology of the fluid collections in the wrist, we elected to aspirate the cysts, yielding approximately 10 cc of gelatinous fluid (see Figure 4). The fluid was too viscous for a cell count and differential to be conducted; however, cultures from both the cyst aspirate and the left ankle effusion ultimately grew Sporothrix (see Figure 5).

The patient was started on intravenous amphotericin, as well as oral itraconazole, and underwent incision and drainage of her left ankle and her right forearm lesions. She required multiple surgeries to address chronic left ankle fungal osteomyelitis, with necrosis involving the tibia, fibula and talus.

The infectious disease team recommended ongoing antifungal therapy with itraconazole, with plans for at least one year of treatment after her most recent surgery.

Discussion

Cognitive biases are known to contribute to medical errors and diagnostic delays, and the care of patients with rheumatologic conditions arguably presents an inherently higher risk for these types of errors.1–3 Distinguishing between fungal infections and autoimmune disease can be challenging and requires both careful evaluation and a high degree of suspicion, particularly related to opportunistic infections.

Given that rheumatologic conditions and indolent fungal infections are relatively uncommon, providers may be unfamiliar with possible disease presentations causing a tendency toward search satisfying, in which consideration of alternatives stops once a plausible explanation is found. Wide variation exists in the estimation of infectious risk associated with commonly used rheumatologic therapies, potentially contributing to biased assessment.4

In this case, premature diagnostic closure and confirmation bias likely led the providers to prematurely lock on the known rheumatologic condition and give undue credence to findings that confirmed this diagnosis, excluding data that argued against RA as the sole cause of her illness.5

Figure 3: X-rays & MRI

The left panel shows an X-ray from admission of the upper right extremity, with notable discrete areas of soft tissue swelling, and radiocarpal joint space narrowing. The middle and right panels show MRI short tau wave inversion sequences, with several areas of mildly complex, enhancing subcutaneous cysts and associated soft tissue edema.

Numerous reports in the literature involve patients who were misdiagnosed with RA, gout or psoriatic arthritis and were only identified as having disseminated sporotrichosis after multiple treatment failures with systemic immunosuppression.6–9

The presentation of Sporothrix arthritis is often variable, with reports of monoarticular, oligoarticular and even polyarticular disease being common. Although skin findings are often present, they are frequently attributable to the suspected underlying disease process.6

There are also reports of misdiagnosis of Sporothrix arthritis with vasculitis, sarcoidosis and pyoderma gangrenosum, with confusion often owing to the presence of mixed granulomatous and suppurative inflammation on histology, often with no apparent fungal elements.10–14 In the majority of these cases, diagnosis was delayed by months despite attempts at biopsy or arthrocentesis, which initially failed to demonstrate the causative organism. The diagnosis was often made when cultures were repeated after patients failed to improve on systemic immunosuppression, likely due to increases in organism burden resulting in improved sensitivity of cultures and histologic examination.10–12

The development of large, painful nodules on exam was also suggestive of a diagnosis other than rheumatoid arthritis. As noted in our exam, these lesions were fluctuant to palpation and quite tender, suggestive of a fluid collection, such as a cyst or abscess. This contrasts with the typically firm, rubbery character of rheumatoid nodules.

Mycotic cysts or pseudocysts may also be mistaken for benign conditions, such as synovial cysts or epidermal inclusion cysts; however, these conditions are usually not associated with worsening inflammatory arthritis and are not typically painful.14

It is also worth emphasizing that although the classic description of sporotrichosis is of lymphocutaneous spread following direct inoculation by contaminated plant matter, other cutaneous and systemic findings can be seen, particularly in immunocompromised patients.15 Cutaneous infection may manifest as nodular or noduloulcerative lesions, ulcers, cysts, pseudocysts or verrucous papular lesions.16

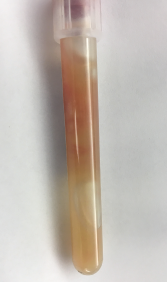

Figure 4

Gelatinous aspirate collected from subcutaneous nodules.

Our patient lacked an obvious history of gardening or rose exposure that would suggest the possibility of sporotrichosis, and yet this should not have excluded the possibility of infection, because a specific exposure is not identified in many cases.

Inoculation with Sporothrix species is classically tied to exposure to plant matter; however, there are also reports of animal-associated disease. In particular, feline-transmitted Sporothrix brasiliensis has been responsible for an epidemic of infections in Brazil.15,17 In osteoarticular infections, the organism may be directly introduced into a joint; however, it may also spread contiguously (as in from skin to joint) or by hematogenous route, in the case of pulmonary inoculation.15,17

Overall, this heterogeneity in possible mechanisms of inoculation creates a diagnostic challenge and illustrates the need for broad differential considerations in immunocompromised patients.

Arguably the most important clue for an infectious process in both our case and for many reported cases in the literature was a failure to respond to what should have been adequate immunosuppression for the treated condition. Although not an ideal long-term therapy, 20 mg of prednisone daily should have provided reasonable control for our patient’s RA.18,19 Her chronic prednisone use at a dose of 20 mg was also an important risk factor for serious infection, particularly with an opportunistic organism.20–23

Disseminated sporotrichosis appears to be more common in patients with compromised cellular immunity. This includes patients on immunosuppressive regimens, but also individuals with HIV/AIDS, diabetes or alcoholism.15

The treatment is generally a combination of amphotericin B and itraconazole, narrowing to itraconazole monotherapy after initial clinical improvement.15–17 The duration of treatment depends on the severity of infection and host immune factors, with long-term (six months to a year) therapy often necessary in immunocompromised patients.15–17

Conclusion

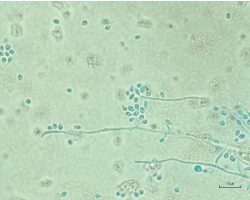

Figure 5. Light microscopy of aspirate culture showing Sporothrix schenckii species.

Although cognitive bias likely played a role in our patient’s initial care, the primary team’s systematic approach and early involvement of appropriate specialists helped prevent the significant delays and misdiagnosis often seen in opportunistic illnesses.

As rheumatologists, our role is not only to diagnose and treat rheumatologic disease, but also to consider alternate explanations and to advocate for thorough and appropriate work-up to reasonably exclude infectious etiologies.

Reducing the impact of cognitive bias in the care of our patients will likely necessitate increasing the available rheumatology workforce, and rheumatology educational opportunities during medical training and for our colleagues in practice.

Sarah Dill, MD, was a third-year rheumatology fellow at the University of Colorado, Aurora, when this article was written. She is now working at the Rocky Mountain Regional VAMC in Aurora, Colo.

Duane Pearson, MD, is an associate professor in the Department of Internal Medicine-Rheumatology at the University of Colorado.

References

- O’Sullivan E, Shofield S. Cognitive bias in clinical medicine. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2018 Sep;48(3):225–232.

- Graber ML, Franklin N, Gordon R. Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Jul 11;165(13):1493–1499.

- Saposnik G, Redelmeier D, Ruff CC, Tobler PN. Cognitive biases associated with medical decisions: A systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016 Nov 3;16(1):138.

- Sharim R, Thomas P, Mathew L, et al. Perceptions of infection risk with immunomodulatory medications. J Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Mar;24(2):80–84.

- Croskerry P. The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Acad Med. 2003Aug;78(8):775–780.

- Yamaguchi T, Ito S, Takano Y, et al. A case of disseminated sporotrichosis treated with prednisolone, immunosuppressants, and tocilizumab under the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Intern Med. 2012;51(15):2035–2039.

- Gottlieb GS, Lesser CF, Holmes KK, Wald A. Disseminated sporotrichosis associated with treatment with immunosuppressants and tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists. Clin Infect Dis. 2003 Sep 15;37(6):838–840.

- Chowdhary G, Weinstein A, Klein R, Mascarenhas BR. Sporotrichal arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991 Feb;50(2):112–114.

- Appenzeller S, Amaral TN, Amstalden EMI, et al. Sporothrix schenckii infection presented as monoarthritis: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2006 Nov;25(6):926–928.

- Byrd DR, El-Azhary RA, Gibson LE, Roberts GD. Sporotrichosis masquerading as pyoderma gangrenosum: Case report and review of 19 cases of sporotrichosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001 Nov;15(6):581–584.

- Yang DJ, Krishnan RS, Guillen DR, et al. Disseminated sporotrichosis mimicking sarcoidosis. Int J Dermatol. 2006 Apr;45(4):450–453.

- White M, Adams L, Phan C, et al. Disseminated sporotrichosis following iatrogenic immunosuppression for suspected pyoderma gangrenosum. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019 Nov;19(11):e385–e391.

- Isa-Isa R, García C, Isa M, Arenas R. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012 Jul–Aug;30(4):425–431.

- Sheikh SS, Amr SS. Mycotic cysts: Report of 21 cases including eight pheomycotic cysts from Saudi Arabia. Int J Dermatol. 2007 Apr;46(4):388–392.

- Queiroz-Telles F, Buccheri R, Benard G. Sporotrichosis in immunocompromised hosts. J Fungi (Basel). 2019 Jan 11;5(1):8.

- Mahajan VK. Sporotrichosis: An overview and therapeutic options. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:272376.

- de Lima Barros MB, de Almeida Paes R, Schubach AO. Sporothrix schenckii and sporotrichosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011 Oct;24(4):633–654.

- Gotzsche PC, Johansen HK. Short-term low-dose corticosteroids vs placebo and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2005(3):CD000189.

- Svensson B, Boonen A, Albertsson K, et al. Low-dose prednisolone in addition to the initial disease-modifying antirheumatic drug in patients with early active rheumatoid arthritis reduces joint destruction and increases the remission rate: A two-year randomized trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Nov;52(11):3360–3370.

- Stuck AE, Minder CE, Frey FJ. Risk of infectious complications in patients taking glucocorticosteroids. Rev Infect Dis. 1989 Nov–Dec;11(6):954–963.

- Dixon WG, Suissa S, Hudson M. The association between systemic glucocorticoid therapy and the risk of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011Aug 31;13(4):R139.

- Dixon WG, Abrahamowicz M, Beauchamp M-E, et al. Immediate and delayed impact of oral glucocorticoid therapy on risk of serious infection in older patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A nested case-control analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Jul;71(7):1128–1133.

- Migita K, Arai T, Ishizuka N, et al. Rates of serious intracellular infections in autoimmune disease patients receiving initial glucocorticoid therapy. PLoS One. 2013 Nov 19;8(11):e78699.