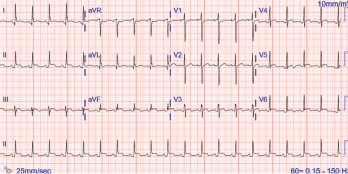

Figure 1. The ECG shows widespread ST elevation, along with PR segment deviation more prominent in leads I, II, AVF and AVR, suggestive of acute pericarditis.

The incidence of drug-induced lupus continues to rise as clinicians expand their therapeutic armamentarium. An estimated 15,000–30,000 cases of drug-induced lupus occur every year in the U.S. alone.1 It is a well-known, but rare, complication of commonly used medications, such as anti-hypertensive, anti-arrhythmic and anti-epileptic drugs, as well as biologic and immune checkpoint therapies.2,3

The mechanism of how drugs cause this autoimmune phenomenon is only partially understood. The complex disease pathophysiology includes such factors as the host’s acetylator status, alterations in innate and adaptive immunity, certain drugs acting as haptogens and the generation of cytotoxic metabolites, which result in an autoimmune reaction, often causing detrimental effects on the target organs.4-6 The most common presenting symptoms of drug-induced lupus overlap with idiopathic systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). These include fever, anorexia, weight loss, fatigue and musculoskeletal symptoms.7 However, the multi-organ manifestations seen in idiopathic SLE are uncommon in drug-induced lupus.

Given the lack of diagnostic criteria, clinicians often rely on the identification of a temporal relationship between administration of the drug and the development of symptoms for diagnosis.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old Black woman with a history of epilepsy who had taken phenytoin and topiramate for seven years presented to our hospital with a one-month history of intermittent, sharp, substernal chest pain and progressive exertional dyspnea. She denied experiencing fever, cough, flu-like symptoms, leg swelling, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, oral ulcers, hair loss, skin rash or Raynaud’s phenomenon.

She had visited two different urgent care facilities prior to this presentation and was prescribed over-the-counter analgesics. On arrival, her blood pressure was 120/73 mmHg, her pulse was 98 beats/minute, her temperature 36.5ºC, and she had a respiratory rate of 22 breaths/minute with normal saturation on ambient air. She had trace pedal edema with decreased breath sounds bilaterally, but an otherwise normal systemic examination.

Complete blood counts revealed a white blood cell count of 5.9×103 cells/μL (normal: 4.5–11.0×103 cells/μL), hemoglobin of 10.0 g/dL (normal: 11–13.5 g/dL) with a mean corpuscular volume of 81.9 fL (normal: 81–99 fL) and platelets of 369×103 cells/μL (normal:150–400 x103 cells/μL). Her inflammatory markers were elevated: erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 65 mm/hr (normal: 0–20 mm/hr) and a C-reactive protein of 30.93 mg/dL (normal: <0.5 mg/dL). Her troponin I was elevated at 1.8 ng/mL (normal: <0.03 ng/mL). She had normal renal and liver functions.

An evaluation for anemia revealed a ferritin level of 82 µg/mL (normal: 11–307 µg/mL), total iron binding capacity of 210 µg/dL (normal: 284–507 µg/dL), transferrin saturation of 6% (normal: 15–50%) and an iron level of 13 mcg/dL (normal: 50–212 mcg/dL). Her serum lactate dehydrogenase was 317 U/L (normal: 140–271 U/L). Her reticulocyte count, peripheral smear and haptoglobin levels were unremarkable.

Her electrocardiogram showed diffuse ST segment elevations with PR segment depressions suggestive of acute pericarditis (see Figure 1).