Recurrent cutaneous eosinophilic vasculitis (RCEV) is a rare autoimmune condition characterized histologically by necrotizing small vessel vasculitis of the skin and almost exclusive eosinophilic infiltration without any systemic involvement.1 Frequently, there is associated peripheral eosinophilia, and a prolonged course of glucocorticoids is required for treatment. To date, only a few RCEV cases have been reported.

Below, we describe a case of biopsy-proven RCEV with distinct, punched, ulcerative lesions and no evidence of peripheral eosinophilia; the patient remained glucocorticoid dependent despite multiple steroid-sparing agents. We also present a review of the literature and discuss the clinical features, histopathological features and differential diagnosis for RCEV.

The Case

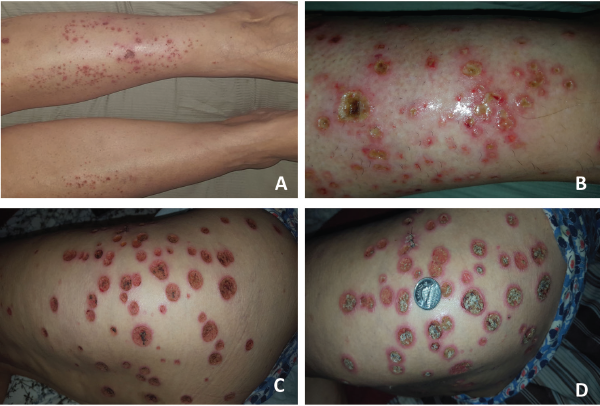

A 75-year-old Caucasian woman presented with a two-year history of recurrent skin eruptions over her legs, buttocks and arms, sparing the trunk. These lesions started as intensely pruritic urticarial lesions that developed into vesicles and pustules and then progressed to eczematous punched ulcers within two to three weeks (see Figures 1A–D, above right). Treatment with antihistamines and antibiotics proved ineffective.

A systems review was otherwise unremarkable. The patient’s past medical history revealed allergic rhinitis that had been quiescent for several years and no history of asthma. Current medications did not include any agents likely to cause a drug eruption.

The complete blood count was unremarkable. Importantly, the patient never had peripheral eosinophilia on initial presentation or throughout the two years of her disease. Tests for anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-extractable nuclear antigen antibodies, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, double-stranded DNA antibodies, serum cryoglobulins and serology for HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C were all negative on several occasions. Complement levels were normal. C-reactive protein was never elevated unless the patient had developed infections.

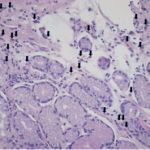

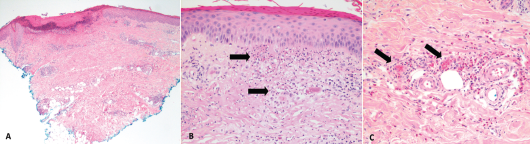

Two bone marrow biopsies to determine a hematological cause of eosinophilic infiltration were unremarkable. The patient also underwent eight skin biopsies, most of which demonstrated eosinophilic infiltration, ulceration and superficial and deep perivascular inflammation with vascular damage (see Figure 2A). Two biopsies showed cutaneous small vessel vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis of vessel walls and surrounding nuclear debris (see Figures 2B & 2C).

Figure 1. These images show the patient’s RCEV ulcerative skin lesions over two weeks, including image A, which shows an intensely pruritic urticarial rash on her lower legs bilaterally; B, which shows progressive worsening and the development of vesicles and pustules with proteinaceous exudates; C, which shows the formation of eczematous, punched ulcers over her buttocks and thighs; and D, an enlarging ulcer base with crusting (and a Canadian quarter placed to demonstrate ulcer size).

Diagnosis

The patient was diagnosed with recurrent cutaneous eosinophilic vasculitis.

We did an extensive search for other organ involvement, which included a normal echocardiogram, non-specific minimal groundglass opacity on chest computed tomography and a mild obstructive pattern on pulmonary function testing in keeping with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The patient also suffered long-standing microscopic hematuria without an active sediment or renal dysfunction, which was attributed to bladder diverticula on cystoscopy and recurrent urinary tract infections.

The patient’s lesions were highly responsive to prednisone, but her skin lesions recurred whenever the prednisone was tapered below 10 mg daily. After two years of glucocorticoid therapy, she developed multiple side effects, including weight gain, osteoporosis and hypomania. She was initially treated with azathioprine, but developed significant nausea and diarrhea, so she was transitioned to 25 mg of methotrexate subcutaneously weekly and 400 mg of hydroxychloroquine daily, which were ineffective in controlling the lesions. Subsequently, tacrolimus was initiated, but she developed acute renal injury, which resolved upon withdrawing tacrolimus. Further therapy escalation to more potent immunosuppression, such as mycophenolate or cyclophosphamide, was limited due to recurrent urinary tract infections with resistant organisms.

She was on 10 mg of prednisone daily and methotrexate when she succumbed to pneumosepsis and respiratory failure.

Figure 2. These hematoxylin and eosin stain images show the patient’s histology of RCEV demonstrating vasculitis, including image A, a biopsy from her right leg showing ulceration and superficial and deep perivascular inflammation with vascular damage (magnification 40X); B, a biopsy from her left leg showing cutaneous small vessel vasculitis (the arrows indicate examples of damaged blood vessels) with fibrinoid necrosis of vessel walls and surrounding nuclear debris/leukocytoclasis (magnification 200X); and C, a biopsy from her right leg showing small vessel vasculitis (arrows), uninvolved adjacent small arterioles and abundant perivascular and interstitial eosinophils (magnification 200X).

Discussion

RCEV was initially described by Chen et al. in 1994 and is characterized clinically by its benign course and classically pruritic skin eruptions. Various skin morphologies have been noted with RCEV, including urticaria, papules, patches, nodules, angioedema and vesicles.1-9 Only one previous group has described RCEV with ulcerating lesions, as we saw in this case.8 The lack of peripheral eosinophilia noted in our case was also unique, and this feature was noted in only three of the 17 cases.4,6,9

Histology can reveal necrotizing vasculitis with predominant eosinophilic infiltration, and others have commented on the presence of neutrophils and lymphocytes.5,8,9 Granulomas and leukocytoclastic features are typically absent in RCEV, although our case did feature some evidence of leukocytoclasis on histology.1-9 A number of specific findings enabled us to rule out similar conditions, such as eosinophilic granulomatous polyangiitis (EGPA), urticarial vasculitis, Wells syndrome and hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES).

Classically, patients with EGPA have asthma, peripheral eosinophilia and leukocytoclastic vasculitis with granulomas on biopsy.10 Urticarial vasculitis typically presents with skin lesions that resolve with pronounced central clearing and hyperpigmentation, rather than vesicles and ulcers.11 Leukocytoclasia is also a key histological feature in urticarial vasculitis.11,12

Patients with Wells syndrome tend to have peripheral eosinophilia and granulomas with no features of vasculitis on biopsy.13 Finally, HES was unlikely in light of the normal bone marrow biopsy and absence of eosinophilia or visceral involvement.14

Despite some atypical features, our patient’s clinical and histological presentation were consistent with RCEV. Glucocorticoids effectively manage RCEV, but recurrence is common after tapering the dose.1-9,15 Some recommend initiation of oral prednisone at 0.5 mg/kg/day and tapering it at two weeks to reach the minimum necessary dose to maintain remission.16

However, only a few known cases of RCEV report successful withdrawal of systemic steroids.5-7 Sakuma-Oyama et al. described RCEV in a 27-year-old female maintained solely on 300 mg of suplatast tosilate daily, a medication also used in eczema and asthma management known to suppress immunoglobulin E, interleukin 4 and interleukin 5.5 Tanglertsampan et al. successfully treated RCEV with 150 mg of indomethacin daily.8 Another group used dapsone in conjunction with glucocorticoids to manage two patients with RCEV.15 Use of other immunosuppressive agents in the treatment of RCEV was described in only one case, in which 2 mg of oral tacrolimus daily allowed prednisone to be tapered.7

In our case, azathioprine actually provided some steroid-sparing benefit, and her prednisone dose was tapered to 5 mg daily. But unfortunately, gastrointestinal side effects (e.g., nausea and diarrhea) prohibited azathioprine’s use. Methotrexate and hydroxychloroquine proved ineffective. Tacrolimus in addition to methotrexate caused kidney injury. Further therapy escalation to stronger immunosuppression, such as mycophenolate or cyclophosphamide, has not been reported and was limited in this case due to recurrent urinary tract infections.

Summary

We described a case of biopsy-proved RCEV that presented with punched, ulcerative skin lesions and no peripheral eosinophilia, both of which are unusual features rarely reported in the literature. RCEV is uncommon, but should remain on the differential diagnosis of necrotizing vasculitis with or without eosinophilia. Although prednisone was effective, the skin lesions recurred with prednisone taper, resulting in prolonged steroid use and multiple side effects.

Limited data exist to guide RCEV treatment, with only one case report of a patient successfully treated with tacrolimus, two with dapsone, one with indomethacin and one with suplatast tosilate.5,7,8,15 Our patient did respond to azathioprine, suggesting its potential use in RCEV. Whether other immunosuppressive agents, such as mycophenolate or cyclophosphamide, would provide any benefit in severe cases remains unclear.

Julia Tan, MD, is an internal medicine resident at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Julia Tan, MD, is an internal medicine resident at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Kun Huang, MD, PhD, is a rheumatologist at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Kun Huang, MD, PhD, is a rheumatologist at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Natasha Dehghan, MD, is a rheumatologist at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Natasha Dehghan, MD, is a rheumatologist at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Neda Amiri, MD, is a rheumatologist at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Neda Amiri, MD, is a rheumatologist at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Martin Trotter, MD, PhD, head of the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at Providence Health Care, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada, for reviewing and preparing the histopathology images of this manuscript.

References

- Chen KR, Pittelkow MR, Su D, et al. Recurrent cutaneous necrotizing eosinophilic vasculitis. A novel eosinophil-mediated syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130(9):1159–1166.

- Launay D, Delaporte E, Gillot JM, et al. An unusual cause of vascular purpura: Recurrent cutaneous eosinophilic necrotizing vasculitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000 Sep–Oct;80(5):394–395.

- Li W, Cao W, Song H, et al. Recurrent cutaneous necrotizing eosinophilic vasculitis: A case report and review of the literature. Diagn Pathol. 2013 Nov 7;8:185.

- Riyaz N, Sasidharanpillai S, Hazeena C, et al. Recurrent cutaneous eosinophilic vasculitis: A rare entity. Indian J Dermatol. 2016 Mar–Apr;61(2):235.

- Sakuma-Oyama Y, Nishibu A, Oyama N, et al. A case of recurrent cutaneous eosinophilic vasculitis: Successful adjuvant therapy with suplatast tosilate. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149(4):901–903.

- Sawada C, Taniai M, Kawashima M, et al. Recurrent cutaneous eosinophilic vasculitis. Eur J Dermatol. 2016 Jan–Feb;26(1):108–109.

- Sugiyama M, Nozaki Y, Ikoma S, et al. Successful treatment with tacrolimus in a case of the glucocorticoid-dependent recurrent cutaneous eosinophilic vasculitis. Ann Dermatol. 2013 May;25(2):252–254.

- Tanglertsampan C, Tantikun N, Noppakun N, et al. Indomethacin for recurrent cutaneous necrotizing eosinophilic vasculitis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2007 Jun;90(6):1180–1182.

- Tsunemi Y, Saeki H, Ihn H, et al. Recurrent cutaneous eosinophilic vasculitis presenting as annular urticarial plaques. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85(4):380–381.

- Crowson AN, Mihm MC Jr, Magro CM. Cutaneous vasculitis: A review. J Cutan Pathol. 2003 Mar;30(3):161–173.

- Venzor J, Lee WL, Huston DP. Urticarial vasculitis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2002 Oct;23(2):201–216.

- Kano Y, Orihara M, Shiohara T. Cellular and molecular dynamics in exercise-induced urticarial vasculitis lesions. Arch Dermatol. 1998 Jan;134(1):62–67.

- Caputo R, Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: A report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006 Sep;142(9):1157–1161.

- Klion AD. How I treat hypereosinophilic syndromes. Blood. 2009 Oct 29;114(18):3736–3741.

- Quijano-Gomero EG, Rodriguez-Zuniga MJM, Sanz-Montero ME, et al. Clinical, dermoscopic and histologic features of recurrent cutaneous eosinophilic vasculitis cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018 Jun 21.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Jan;65(1):1–11.