Rheumatologists are in the unique position of diagnosing and treating rare auto-inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Although systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) often has textbook presentations, it is a heterogeneous condition with a wide variety of disease manifestations.

In 2019, the European League Against Rheumatism and the ACR introduced new classification criteria to help diagnose this condition.1 These criteria use a point-based system to demonstrate an increased likelihood a patient has lupus.

We present a case that illustrates the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for lupus with unusual clinical presentations, because these presentations can sometimes be life-threatening.

Case Presentation

AB is a 30-year-old Black woman with a past medical history of asthma who was transferred to a tertiary care center with dyspnea, fevers, anemia and thrombocytopenia.

Her symptoms began about three months prior to presentation. At that time, she went to the emergency department with menorrhagia and was found to have anemia and severe thrombocytopenia, with platelets less than 5 k/µL. She was treated immediately with high-dose, intravenous (IV) dexamethasone and one dose of 1 g/kg IV immunoglobulin. During that admission, she was noted to have left-sided inguinal lymphadenopathy and, ultimately, underwent a lymph node biopsy, which showed reactive changes without any evidence of malignancy. Her thrombocytopenia and anemia resolved.

Approximately two months prior to her current admission, she presented to an urgent care facility with a weeklong history of headaches and fevers. A computed tomography (CT) scan of her head and a lumbar puncture were unremarkable. She was found to have thrombocytopenia again and started on 60 mg of oral prednisone daily. Her thrombocytopenia improved. Her headaches were diagnosed as migraines and resolved with analgesics.

One month prior to this admission, her outpatient hematologist had noted progressive anemia and thrombocytopenia despite high-dose oral steroids and initiated 375 mg/kg2 rituximab for four weekly doses. Her second weekly infusion was held because the patient had developed fevers and malaise. She was admitted to the hospital and subsequently transferred to a tertiary care center after her hemoglobin was found to be 3.7 mg/dL.

Her past medical history was notable for congenital hip dysplasia and uterine fibroids. The remainder of a review of systems was notable for dry mouth, palpitations and abdominal bloating. She had no significant family history and denied tobacco, alcohol or drug use. The patient had no prior pregnancies, miscarriages or abortions. Her only drug allergy was morphine.

On exam, her heart rate was 140 beats per minute and regular. Her blood pressure was 120/68 mmHg. Her respirations were 20 per minute, and she was febrile, with a temperature of 102.9°F (39.4°C). Her oxygen saturation was 99% on room air. Her physical exam was notable for regular tachycardia without murmurs, oral thrush, mild frontal alopecia, and non-tender anterior cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy. Her lungs were clear to auscultation, and her abdominal exam was normal.

Her anti-nuclear antibodies were positive at 1:640 with a speckled pattern. Her anti-cardiolipin IgM antibody was mildly elevated at 12.9 MPL, and her IgG antibody was negative. Her anti-β-2 glycoprotein IgG and IgM antibodies were negative.

Lupus anticoagulant screening and confirmatory dilute Russell viper venom time test were both positive. Other positive labs included elevated anti-ribonucleoprotein antibody at 130 units (normal <20 units) and anti-Smith antibody at 52 units (normal <20 units). Her autoimmune studies were otherwise negative, including antibodies against double-stranded DNA and DNA (Crithidia), SSA, SSB, Scl-70, cyclic citrullinated peptide and Jo-1.

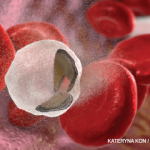

Her complements were low. Coombs testing was positive, and labs were consistent with hemolysis (i.e., lactate dehydrogenase enzyme was elevated at 1,206 U/L and haptoglobin was less than 15 mg/dL). An infectious workup showed possible pneumonia on a chest X-ray with lower lobe consolidations. She had negative blood and urine cultures, but did not have serologic evidence for hepatitis, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus-6, parvovirus B19 PCR, mycoplasma, human immunodeficiency virus, Bartonella, Brucella, or histoplasmosis and blastomycosis antigens. Urine pregnancy testing was negative.

Table 1 shows the patient’s laboratory findings.

| Three months prior | Two months prior | Current admission | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (K/UL) | 3.6 | 7.4 | 13.2 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 8.3 | 6 | 3.7 |

| Platelets (K/UL) | 5 | 85 | 323 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.87 | 0.67 | 1 |

| AST (IU/L) | 36 | 43 | 59 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 32 | 43 | 41 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3 | 3.48 | 2.4 |

A bone marrow biopsy of her left iliac crest showed bone marrow that was 80–90% cellular with progressive trilineage hematopoiesis. A peripheral smear showed macrocytic anemia. Positron emission tomography scan revealed multiple diffuse hypermetabolic lymph nodes, and a CT scan demonstrated hepatosplenomegaly.

She was started on IV cefepime and vancomycin, oral metronidazole and inhaled nebulizers. The patient was also started on 1 mg/kg/day of methylprednisolone for three days. She received transfusions of platelets and red blood cells. Her blood counts improved over the course of a week with corticosteroid administration, and she was also given a dose of rituximab 375 mg/kg with plans to continue this treatment as an outpatient. She was discharged to follow-up on 60 mg of prednisone daily.