Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is a type of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated small vessel vasculitis that typically affects the kidneys, lungs and sinuses.1 Due to an overlap in signs and symptoms, GPA may initially be difficult to distinguish from IgG4-related disease, another condition that can affect multiple tissues and has variable presentations. Further complicating the diagnosis is that GPA is not always associated with an anti-proteinase 3 (PR3) antibody.2 Whether by extension through the sinuses or more directly, GPA can clinically present with inflammation of ocular structures. This presentation of GPA is rarer in children than in adults.3

The Case

An 11-year-old girl was sent to the emergency department by her primary care provider due to elevated inflammatory markers in the setting of intermittent hematuria and proteinuria. Laboratory testing at that time showed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 114 mm/hr (reference range [RR]: 1–10 mm/hr).

Laboratory tests were repeated in the emergency department, with similar findings, including an elevated ESR of 116 mm/hr. Her C-reactive protein was also elevated at 1.2 mg/L (RR: <0.9 mg/L). A urinalysis showed trace ketones, moderate blood and mild proteinuria. Overall, she was well-appearing with no other symptoms. She was discharged with a plan to follow up with a rheumatologist.

Despite the abnormal lab values, the patient appeared well and relatively asymptomatic at first consultation in our clinic, one month after her emergency department visit. She had no ocular symptoms, epistaxis or sinus pain. However, she had a history of frequent aphthous ulcers and a recent lymphadenopathy along the right side of her neck. A review of systems was otherwise unremarkable.

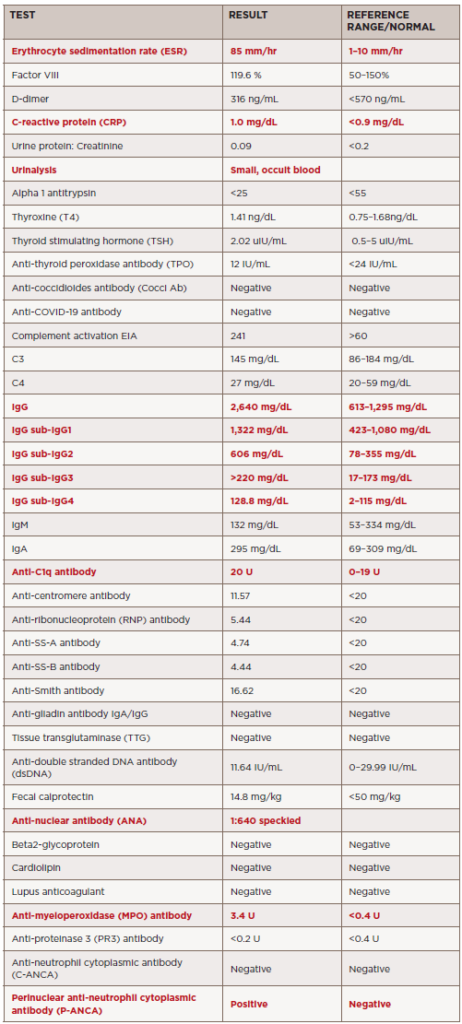

Due to the elevated inflammatory markers and the above history, additional laboratory tests were ordered, revealing the presence of antimyeloperoxidase antibody, perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (P-ANCA) and anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), as well as anti-C1q antibody (see Table 1). The comprehensive metabolic panel, including creatinine, and complete blood count were unremarkable.

An ultrasound of the abdomen and neck was performed due to the patient’s intermittent lymphadenopathy; the results were unremarkable.

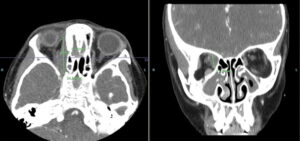

Computerized tomography (CT) of the lungs revealed no evidence of lung disease. However, a CT of the sinuses showed severe mucosal thickening within the ethmoid air cells, “with focal dehiscence of the right lamina papyracea.” A soft tissue mass was present within the medical extraconal space of the right orbit, affecting the right optic nerve, right globe and extraocular muscles. Findings were concerning for an inflammatory mass, such as an orbital pseudotumor. The radiologist considered infection unlikely.

Sinus disease was also found within the right maxillary sinus, with complete obliteration and underlying periosteal thickening. Circumferential mucosal thickening, with aerated secretions within the left maxillary sinus extending into the left ethmoid infundibulum, was seen.

Due to these findings, the patient was admitted to the hospital for expedited evaluation by, and consultation with, both an otolaryngologist and an ophthalmologist.

Hospital Course

On admission—two months after her first emergency department visit—her physical examination showed proptosis of the right eye with slight edema, compared with the left eye. This was a new finding. Despite the proptosis and mild edema, extraocular movements were intact. She did have lymphadenopathy that was worse along the right side of her neck. Otherwise, the examination was unremarkable. During questioning, she said she began to have blurry vision while in the emergency department that day.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a right medial, orbital mass encasing the right trochlear and medial rectus muscles (see Figure 1). The mass was non-uniform, with variable signal intensity. Again, imaging favored a non-infectious inflammatory process over infection. Pansinusitis with osseous destruction of the medial maxillary sinus walls was visualized on the right. The laboratory testing was expanded to include IgG subclasses to evaluate for IgG4 disease; all IgG subclasses were elevated (see Table 1).

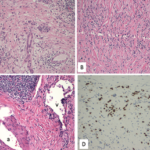

The patient underwent biopsies of both the sinuses and the orbit shortly after admission. The hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain from the sinus biopsy showed densely collagenous fibrotic background with focal chronic inflamAnmation including many plasma cells in three of five fragments. Small vessels, including arterioles, had concentric or periarterial fibrosis with edematous changes. Focal neutrophilic vasculitis was noted. Classic fibrinoid necrosis was not seen on the slides examined. No granulomas, fungi or viral inclusions were identified. No evidence of neoplasm or malignancy was seen.

The biopsy from the orbit showed dense fibrous and adipose tissue with focal, chronic inflammation. Findings were difficult to fully examine due to extensive crush artifact (i.e., damaged tissue caused by iatrogenic compression of the tissue during collection; it can often result from firm handling with forceps, fingers or other instruments). Despite this, the small vessels were revealed to have concentric or periarterial fibrosis with edematous change. No granulomas, fungi or viral inclusions were identified, and no evidence of neoplasm or malignancy was seen.

Both biopsies were reviewed with the pathologist, and the findings from both the sinus and ocular biopsies appeared to be part of the same underlying process and not two different etiologies. A diagnosis of IgG4-related disease was considered unlikely based on her immunohistochemistry and laboratory testing (see Table 1). Given the biopsy results, early ANCA-associated vasculitis was considered more likely. Based on her presentation, biopsies and laboratory values, the patient was subsequently diagnosed with GPA.

After diagnosis, the patient received pulse therapy with glucocorticoids (30 mg/kg/dose = 800 mg) for three days and then transitioned to 20 mg of oral prednisone twice a day, followed by a prednisone wean. She was given rituximab induction therapy (750 mg x two doses, two weeks apart) followed by maintenance therapy (thus far receiving one dose). Currently, she has been weaned off prednisone and is doing well overall, with minimal symptoms.

A follow-up MRI eight months later showed markedly decreased orbital mass, with only a small residual area of enhancement between the right medial rectus and superior oblique muscle. There was also slightly decreased pansinusitis, with osseous destruction of the medial maxillary sinus walls and dehiscence of the right lamina papyracea. Further, the anterior cranial fossa pachymeningeal thickening and enhancement was nearly resolved.

Discussion

Orbital lesions can be caused by a wide range of conditions, including infection, malignancy, foreign bodies, idiopathic or even autoimmune/inflammatory conditions. Those that are caused by inflammatory manifestations are rare in children, but some reports suggest an average onset at about 12 years of age.3,4 In a case series of children with orbital masses, the most common final diagnosis was granulomatosis with polyangiitis.3

Ocular findings in GPA are rarer in children than adults, where they can occur in up to 60% of cases. Reports indicate that up to 16% of adults initially present with orbital inflammatory involvement.5 Orbital GPA can be secondary to extension of sinus disease or isolated inflammation of the orbit itself.6 The most common presenting signs of orbital disease are ptosis, proptosis, pain, blurred vision, eyelid swelling and reduction of eye mobility.

A few case reports have discussed orbital tumors as initial manifestations of GPA in children.7 In one case series, four children presented with unilateral proptosis and ptosis due to an orbital tumor. Further, cases of GPA with orbital mass that can appear like IgG4-related disease have been reported.8 These presentations are strikingly similar to our patient. The tissues from our patient and the case report mentioned above both showed fibrosis with small and medium vessel vasculitis.

Although many of the clinical and radiographic findings are nonspecific for GPA, biopsy in conjunction with these findings can help differentiate this diagnosis from other potential etiologies, including IgG4-related disease. One general histologic finding that may be helpful in suggesting a diagnosis of GPA over other orbital inflammatory diseases is the presence of many scattered eosinophils, particularly eosinophils within granulomas.9

As in this case, it can be difficult to initially distinguish between IgG4-related disease and ANCA-associated vasculitis. Increased numbers of IgG4-positive plasma cells in an orbital biopsy alone are not sufficient to distinguish IgG4-related disease from GPA.10 Other histopathologic features of IgG4-related disease include storiform fibrosis, dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates and the relative paucity of necrosis and acute inflammation. These can be helpful in distinguishing IgG4-related disease of the eye from orbital GPA. Due to the above factors, as well as the presentation and laboratory findings, our patient was subsequently diagnosed with GPA instead of IgG4-related disease.

Historically, orbital involvement with GPA has been associated with a more difficult course, often including refractory disease.11,12 Interestingly, the more refractory courses have been associated, at least in adults, with anti-proteinase 3 positive antibody. These cases have even been known to lead to visual loss and other sequela of long-standing disease. Luckily, children with ocular GPA have responded well to treatment with high-dose glucocorticoids and rituximab.13 This response is also being seen in our patient.

Geoffrey E. Thiele, MD, is a second-year pediatric rheumatology fellow at Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles. He attended the University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Medicine, Omaha, and completed his residency at Phoenix Children’s Hospital, both of which cemented his interest in the field of pediatric rheumatology.

Geoffrey E. Thiele, MD, is a second-year pediatric rheumatology fellow at Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles. He attended the University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Medicine, Omaha, and completed his residency at Phoenix Children’s Hospital, both of which cemented his interest in the field of pediatric rheumatology.

Sara Haro, MD, is a pediatric rheumatologist practicing at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. Her clinical interests include juvenile idiopathic arthritis and musculoskeletal ultrasound.

Sara Haro, MD, is a pediatric rheumatologist practicing at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. Her clinical interests include juvenile idiopathic arthritis and musculoskeletal ultrasound.

References

- Garlapati P, Qurie A. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis in: StatPearls. Treasure Island (Fla.): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557827.

- Schirmer JH, Wright MN, Herrmann K, et al. Myeloperoxidase-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-positive granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s) is a clinically distinct subset of ANCA-associated vasculitis: A retrospective analysis of 315 patients from a German vasculitis referral center. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016 Dec;68(12):2953–2963.

- Boulter EL, Eleftheriou D, Sebire NJ, et al. Inflammatory lesions of the orbit: A single paediatric rheumatology centre experience. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012 Jun;51(6):1070–1075.

- Belanger C, Zhang KS, Reddy AK, et al. Inflammatory disorders of the orbit in childhood: A case series. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010 Oct;150(4):460–463.

- Vischio JA, McCrary CT. Orbital Wegener’s granulomatosis: A case report and review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2008 Oct;27(10):1333–1336.

- Wardyn KA, Ycińska K, Matuszkiewicz-Rowińska J, Chipczyńska M. Pseudotumour orbitae as the initial manifestation in Wegener’s granulomatosis in a 7-year-old girl. Clin Rheumatol. 2003 Dec;22(6):472–474.

- Chipczyńska B, Grałek M, Hautz W, et al. Orbital tumor as an initial manifestation of Wegener’s granulomatosis in children: A series of four cases. Med Sci Monit. 2009 Aug;15(8):CS135–CS138.

- Drobysheva A, Fuller J, Pfeifer CM, Rakheja D. Orbital granulomatosis with polyangiitis mimicking IgG4-related disease in a 12-year-old male. Int J Surg Pathol. 2018 Aug;26(5):453–458.

- Ahmed M, Niffenegger JH, Jakobiec FA, et al. Diagnosis of limited ophthalmic Wegener granulomatosis: Distinctive pathologic features with ANCA test confirmation. Int Ophthalmol. 2008 Feb;28(1):35–46.

- Deshpande V, Zen Y, Chan JK, et al. Consensus statement on the pathology of IgG4-related disease. Mod Pathol. 2012 Sep;25(9):1181–1192.

- Durel CA, Hot A, Trefond L, et al. Orbital mass in ANCA-associated vasculitides: Data on clinical, biological, radiological and histological presentation, therapeutic management, and outcome from 59 patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019 Sep 1;58(9):1565–1573.

- Berti A, Kronbichler A. Orbital masses in ANCA-associated vasculitis: An unsolved challenge? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019 Sep 1;58(9):1520–1522.

- Riancho-Zarrabeitia L, Peiró Callizo E, Drake-Pérez M, et al. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis with isolated orbital involvement in children: A case report successfully treated with Rituximab and review of literature. Acta Reumatol Port. 2019 Jul 8;44( Jul-Sep (3)):258–263.