Renal osteodystrophy is associated with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and its associated metabolic derangements, most commonly CKD stages 3–5. It is often subclassified into four histological subtypes, with definite distinctions unable to be made clinically. These four subtypes, which may only be differentiated by bone biopsy, include: osteitis fibrosa cystica, mixed uremic osteodystrophy, osteomalacia and adynamic bone disease (see Subtypes of Osteodystrophy sidebar below).

Renal osteodystrophy occurs as a consequence of derangements in parathyroid hormone (PTH), phosphate and vitamin D that affect bone remodeling, leading to pathologically high or low bone turnover. Secondary hyperparathyroidism is the leading cause of renal osteodystrophy.1

In the following case report, we discuss a patient with end-stage renal disease who presented to the hospital with significant hip pain that was originally attributed to a septic joint on the basis of imaging findings. We highlight the role of radiography in diagnosing renal osteodystrophy, highlighting the dangers of relying on imaging findings.

Case Report

A 59-year-old woman with end-stage renal disease, complicated by secondary and tertiary hyperparathyroidism, who had been on hemodialysis for 14 years, presented with severe, intermittent, progressive left hip pain for two to three months leading up to admission. She denied any trauma to the area, fevers at home or other symptoms. Her pain was unrelieved by morphine, and she was unable to walk or move the hip given the severity of the pain. She denied morning stiffness or other joint pain, as well as a personal or family history of autoimmune disease. She had no known preceding viral illness.

On presentation, she was afebrile and non-tachycardic. Blood cultures were negative. A physical exam revealed full range of motion in both hips, but was notable for tenderness with internal and external rotation of the left hip. No other joint swelling was noted.

Her hemoglobin at baseline was 9.1 g/dL. Her white blood cell count was 5.7 B/L and remained within normal limits. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 30 mm/hour, and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 0.82 mg/dL. Parathyroid hormone intact was elevated at 2,305 pg/dL, calcium was 9.54.6 mg/dL, and phosphorous was elevated at 4.6 mg/dL. Alkaline phosphatase was elevated at 286 units/L.

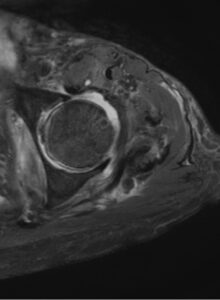

FIGURE 1: T2-weighted axial MRI of the hip with contrast showing periarticular erosion and left hip joint effusion. (Click to enlarge.)

An X-ray of her left hip revealed loss of the subchondral bone along the acetabulum concerning for a septic joint. She then had a computerized tomography (CT) scan of the hip that showed background changes of renal osteodystrophy involving the osseous structures of the bilateral sacroiliac joints and bilateral hip articulations, with findings concerning for superimposed left hip joint septic arthritis. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan revealed a large joint effusion, periarticular erosion and synovitis, as well as edema involving the left periarticular musculature, most pronounced in the adductor compartment (see Figure 1).