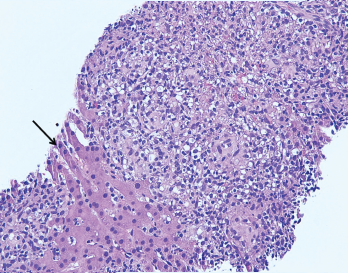

Figure 2. The image from Figure 1 at 200X showing granulomas accompanied by scattered admixed lymphocytes without discernible atypia. Adjacent hepatocytes (black arrow), polygonal cells with centrally placed nucleus and eosinophilic cytoplasm, can also be identified.

A liver biopsy performed on hospital day 3 revealed granulomatous hepatitis (see Figures 1 & 2) but no hemophagocytosis. Iron stains, periodic acid-Schiff diastase stain, immunohistochemistry for cytomegalovirus, and in situ hybridization for Epstein-Barr virus RNA were negative. Subsequent Grocott’s methenamine silver (GMS) stain showed scattered yeast forms (see Figure 3), morphologically consistent with Histoplasma capsulatum. Acid-fast bacillus and Gram stains were negative. Liver tissue culture was not obtained. Serum and urine histoplasma antigens and 1,3 beta-D-glucan were elevated.

A repeat CT of her chest with contrast demonstrated left lower lobe consolidation and incidentally revealed multiple hypodense splenic lesions attributed to a suspected underlying infectious process.

In the setting of multi-organ involvement of histoplasmosis (lung, liver, spleen and lymph nodes), treatment with intravenous liposomal amphotericin B (3 mg/kg/day) was initiated and methylprednisolone discontinued. Anakinra was continued to treat MAS secondary to disseminated fungal infection.

Bone marrow biopsy ultimately revealed hemophagocytosis with engulfment of erythrocyte precursors by macrophages, as well as scattered foci of loosely aggregated histiocytes suggestive of poorly formed granulomas. GMS stain was negative; bone marrow cultures were not performed. An interleukin-2 (IL-2) soluble receptor α was elevated at 8,600 U/mL (RR: 223–710 U/mL), further supporting a diagnosis of MAS.

The patient became consistently afebrile on hospital day 7, and lab abnormalities improved. On hospital day 12, she was discharged on anakinra at a dosage of 100 mg twice daily and a two-week course of intravenous liposomal amphotericin B. She remained off immunosuppressant medications.

Following discharge, the patient continued to improve. One month following hospital discharge, her laboratory abnormalities returned to normal. Upon completion of amphotericin, she transitioned to treatment with oral itraconazole. The serum and urine histoplasma antigen levels returned to normal after three months of itraconazole. She developed a pJIA flare while on anakinra without other immunosuppressive treatment. After discussion with consultants and her pediatric rheumatologist, she resumed infliximab with subsequent improvement.

The patient continues on oral itraconazole as a secondary histoplasma prophylaxis as long as she requires immunosuppressive therapy.

Discussion

Macrophage activation syndrome has been reported in most rheumatic diseases, typically triggered by infection (as seen in our patient) in the setting of immunosuppressive therapy. The syndrome is commonly described in association with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA), in which viral infections remain the most commonly identified trigger, although a broad range of bacterial and fungal infections is capable of initiating the systemic inflammatory response. As seen here, histoplasmosis has been described as a trigger, but is noted only in case reports or case series.1

Diagnosis

The most common clinical features of MAS are high, non-remitting fever, hepatosplenomegaly, generalized lymphadenopathy, central nervous system dysfunction and hematologic abnormalities. Pyrexia is a cardinal feature of the disease.2 Hyperferritinemia is highly characteristic of MAS; a serum ferritin level >10,000 mg/L has a sensitivity and specificity of 96% and 90%, respectively.3 On the other hand, a low fibrinogen as a consequence of the hyperinflammatory state can result in a paradoxical drop in sedimentation rate.4