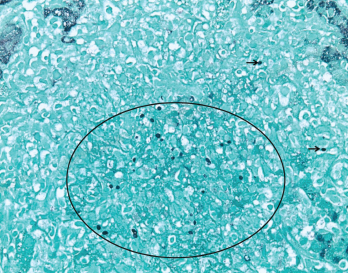

Figure 3. GMS (Grocott’s methenamine silver stain) at 400X highlights scattered yeast forms (black circle and black arrows) morphologically consistent with Histoplasma capsulatum.

The 2016 MAS classification criteria approved by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the ACR call for a febrile patient with known sJIA to have a ferritin of >684 ng/mL as well as two other laboratory findings that may include a platelet count of 181,000/mL, AST >48 units/L, triglycerides >155 mg/dL and/or a fibrinogen ≤360 mg/dL.2 Although these criteria are helpful in the recognition of MAS, they were created to standardize the definition of the MAS patient for clinical studies. The condition remains difficult to definitively diagnose early in the disease course.

The hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) 2004 guidelines are often used in clinical practice to aid diagnosis. One retrospective study assessed the ability of these criteria to differentiate between sJIA-associated MAS, active sJIA and systemic infectious diseases. When three out of five HLH-2004 criteria (i.e., fever, splenomegaly, peripheral blood cytopenias affecting two of three cell lineages, hypertriglyceridemia or hypofibrinogenemia, and evidence of hemophagocytosis) were met, these criteria reached 98% specificity in identifying sJIA patients with MAS vs. those with a systemic infectious disease (κ coefficient=0.74).5

The adapted HLH-2004 criteria did not include soluble interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2r) because it was not collected in all studied patients. However, this marker remains a useful tool due to its low cost and commercial availability. The receptor is upregulated in activated T cells and thus found in high levels in hemophagocytic conditions, lymphomas and other conditions with T cell activation.

One single-center, retrospective study assessed the diagnostic value of this marker in 78 patients with suspected HLH (38 would be diagnosed using HLH-2004 criteria and 40 would have other diagnoses). An sIL-2r value of >2,515 U/mL yielded a test sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 72.5%, whereas a value of >10,000 U/mL increased the specificity to 93%.6

Hemophagocytosis does not correlate with MAS activity or clinical disease, and its absence should not exclude the diagnosis. It is recognized now that hemophagocytosis occurs later in the disease course.7 Our patient met all five of the adapted criteria, displayed an elevated sIL-2r, and her bone marrow biopsy revealed hemophagocytosis, collectively underscoring an MAS diagnosis and the need to treat both MAS and disseminated histoplasmosis. She improved with parallel therapy directed at both conditions.

Treatment

Successful treatment with anakinra in pediatric patients with MAS has been documented in multiple case reports over the years (doses 1 mg/kg/day to 2 mg/kg/day), and this immunosuppressive is used increasingly as an initial therapy.8

To better understand the role of anakinra in patients with features of MAS, a re-analysis of a prospective, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial evaluating all-cause mortality with addition of anakinra in adult patients with severe sepsis was performed on a smaller subset of patients with features of MAS, such as hepatobiliary dysfunction and disseminated intravascular coagulation. They were compared against those who had one or neither of these characteristics and actually showed an improvement in 28-day mortality.9 In this trial, a dose of 2 mg/kg/hr intravenously for 72 hours was studied.

No validated treatment protocols exist for MAS. Management strategies are derived from retrospective studies and from experience treating familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. These approaches usually involve a combination of immunosuppressive agents. Although monotherapy with high-dose steroids has been described as successful, up to 50% of reported adult cases are resistant.10

Recent collaborative work has underscored the need for early and aggressive immunosuppression and simultaneous treatment targeting the underlying inciting infection. Other protocols call for pulse-dose glucocorticoids (i.e., 1 g of methylprednisolone daily for three to five days), followed by intravenous immunoglobulin 1 g/kg daily for two days, with anakinra should there be any clinical deterioration.10 Alternatively, anakinra in a 100 mg subcutaneous dose four times a day may be effective.11 Underlying disorders that may be contributing should be treated concurrently, and malignancy should be considered if a clear insult is not found. We chose the dose of 100 mg subcutaneously every eight hours (3.9 mg/kg/day) due to the efficacy and safety at higher doses alluded to in these trials. IL-1 inhibition is generally not associated with the risk of opportunistic infection.11

Disseminated histoplasmosis in immunocompromised patients may mimic MAS at onset. It also presents as an acute febrile illness associated with fatigue and weight loss.12 Histoplasmosis should be on the differential in immunocompromised patients with systemic febrile diseases, particularly those residing in endemic areas, such as the Midwestern and Central U.S., along the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, as seen in our patient.

The estimated U.S. incidence of histoplasmosis in patients on infliximab is 18.78 per 100,000.13 National Medicare claims data suggests an incidence of 6.1 per 100,000 in the general population in the Midwestern U.S.14

Identification of recent exposure is difficult, and reactivation of latent histoplasmosis can occur years after initial exposure.15 Pulmonary symptoms, such as cough and dyspnea, may not be present. Hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathy may be appreciated on physical exam or imaging. Laboratory testing commonly reveals pancytopenia and hepatic enzyme abnormalities, as may be seen in MAS. Some patients may present with or progress to severe shock with respiratory distress and multisystem organ failure.12

Central nervous system (CNS) involvement is present in 5–10% of cases of disseminated histoplasmosis and can present with a wide variety of clinical and imaging findings.16 Fortunately, our patient had no neurologic symptoms or exam abnormalities over her disease course, thus no lumbar puncture or neurologic imaging was obtained.

Establishing the diagnosis of disseminated histoplasmosis is challenging because malignancy, infection and other inflammatory conditions may present with similar findings. In these patients it is prudent to pursue the diagnosis through histopathology from affected sites and/or antigen detection.17 Cultures may take several weeks of incubation for a result.

Treatment recommendations from the Infectious Diseases Society of America in 2007 are based on severity of infection and the presence of CNS involvement.18 For moderate to severe disseminated disease, the recommended treatment is liposomal amphotericin B for one to two weeks, followed by oral itraconazole for a total of at least 12 months. Patients with CNS involvement should receive a longer course of liposomal amphotericin B at higher doses followed by oral itraconazole. All patients are advised to undergo routine serum and urine antigen testing to assess response to treatment. Some patients with underlying immunocompromising conditions may benefit from lifelong suppressive therapy with itraconazole.

In Sum

We present a case of a young female from the Midwest on immunosuppressive treatment for pJIA and Crohn’s disease who was evaluated for fevers, transaminitis, hyperferritinemia and an acute inflammatory response. The evaluation revealed disseminated histoplasmosis complicated by MAS. In this setting, consideration should be given to both infectious triggers of MAS and MAS mimickers, of which disseminated histoplasmosis remains a rare but important type.

Osman Bhatty, MD, is currently a practicing rheumatologist at Advocate Aurora Health, Chicago.

Osman Bhatty, MD, is currently a practicing rheumatologist at Advocate Aurora Health, Chicago.

Dale Kobrin, MD, is an internal medicine resident at Allegheny General Hospital, Pittsburgh, Pa., and will be starting rheumatology fellowship at the National Institutes of Health in July 2022.

Dale Kobrin, MD, is an internal medicine resident at Allegheny General Hospital, Pittsburgh, Pa., and will be starting rheumatology fellowship at the National Institutes of Health in July 2022.

Lauren Mathos, DO, is an academic internist practicing primary care at Allegheny Health Network, Pittsburgh, Pa.

Lauren Mathos, DO, is an academic internist practicing primary care at Allegheny Health Network, Pittsburgh, Pa.

Nazia Khatoon, MD, completed her pathology training at Allegheny Health Network.

Yazan Samhouri, MD, is a hematologist and cellular therapist. He is in practice at Allegheny Health Network Cancer Institute, Pittsburgh, Pa.

Yazan Samhouri, MD, is a hematologist and cellular therapist. He is in practice at Allegheny Health Network Cancer Institute, Pittsburgh, Pa.

Naga Sai Krishna Patibandla, MD, is a third-year hematology oncology fellow at Allegheny Health Network, Pittsburgh, Pa.

Naga Sai Krishna Patibandla, MD, is a third-year hematology oncology fellow at Allegheny Health Network, Pittsburgh, Pa.

Mary Chester M. Wasko, MD, MSc, is emeritus professor of rheumatology for the Allegheny Health Network, Pittsburgh, Pa.

Mary Chester M. Wasko, MD, MSc, is emeritus professor of rheumatology for the Allegheny Health Network, Pittsburgh, Pa.

References

- Agarwal S, Moodley J, Ajani Goel G, et al. A rare trigger for macrophage activation syndrome. Rheumatol Int. 2011 Mar;31(3):405–407.

- Ravelli A, Minoia F, Davì S, et al. 2016 classification criteria for macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology/Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation collaborative initiative Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016 Mar;68(3):566–576.

- Allen CE, Yu X, Kozinetz C, et al. Highly elevated ferritin levels and the diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008 Jun;50(6):1227–1235.

- Lerkvaleekul B, Vilaiyuk S. Macrophage activation syndrome: Early diagnosis is key. Open Access Rheumatol. 2018 Aug 31;10:117–128.

- Davì S, Minoia F, Pistorio A, et al. Performance of current guidelines for diagnosis of macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Oct;66(10):2871–2880.

- Hayden A, Lin M, Park S, et al. Soluble interleukin-2 receptor is a sensitive diagnostic test in adult HLH. Blood Adv. 2017 Dec;1(26):2529–2534.

- C, Yao X, Tian L, et al. Marrow assessment for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis demonstrates poor correlation with disease probability. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014 Jan;141(1):62–71.

- Henderson LA, Cron RQ. Macrophage activation syndrome and secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in childhood inflammatory disorders: Diagnosis and management. Paediatr Drugs. 2020 Feb;22(1):29–44.

- Shakoory B, Carcillo JA, Chatham WW, et al. Interleukin-1 receptor blockade is associated with reduced mortality in sepsis patients with features of macrophage activation syndrome: Reanalysis of a prior phase III trial. Crit Care Med. 2016 Feb;44(2):275–281.

- Carter SJ, Tattersall RS, Ramanan AV. Macrophage activation syndrome in adults: Recent advances in pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019 Jan 1;58(1):5–17.

- Salvana EM, Salata RA. Infectious complications associated with monoclonal antibodies and related small molecules. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009 Apr;22(2):274–290.

- Wheat LJ. Diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989 May;8(5):480–490.

- Wallis RS, Broder M, Wong J, et al. Reactivation of latent granulomatous infections by infliximab. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Aug 1;41 Suppl 3:S194–S198.

- Baddley JW, Winthrop KL, Patkar NM, et al. Geographic distribution of endemic fungal infections among older persons, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011 Sep;17(9):1664–1669.

- Keath EJ, Kobayashi GS, Medoff G. Typing of Histoplasma capsulatum by restriction fragment length polymorphisms in a nuclear gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1992 Aug;30(8):2104–2107.

- Wheat J, Myint T, Guo Y, et al. Central nervous system histoplasmosis: Multicenter retrospective study on clinical features, diagnostic approach and outcome of treatment. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Mar;97(13):e0245.

- Kauffman CA. Histoplasmosis: A clinical and laboratory update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007 Jan;20(1):115–132.

- Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Oct;45(7):807–825.