Image Credit: BKD1/shutterstock.com

“Worst of all is the pain in my calves,” she said. “It feels like burning deep inside.” So began my first encounter with a 69-year-old woman who was referred to rheumatology clinic for evaluation of two months of constitutional symptoms and a positive ANCA test, which had been ordered by her primary care doctor. Her symptoms began in December, with fever, chills, non-productive cough and hoarseness.

She was treated with guaifenesin for a presumed viral upper respiratory infection, but two weeks passed, and the patient felt no better. Her fevers persisted, and she developed myalgias, fatigue and pain in the hands, knees and ankles without joint swelling or redness. She had no sinus symptoms, sore throat, cough, ear pain, headache, dysuria, recent travel or sick contacts. She saw her primary care doctor, who noted trace bilateral calf edema and tenderness in the MCPs, PIPs and ankles without joint fullness.

For workup of persistent fevers, fatigue and myalgia, her primary care physician checked labs, which revealed mild leukocytosis (WBC 13.1) with a normal differential, mild anemia (HCT 34.2), thrombocytosis (Plt 458), normal creatinine (0.85) and a normal liver panel (ALT 19, AST 25, AlkP 150, T.bili 0.4, albumin 3.8) with the exception of elevated globulin (4.9). Acute-phase reactants were markedly elevated, with ESR 94 and CRP 107. Hepatitis C antibody and Lyme ELISA were negative, and TSH was low (0.3). These results prompted further bloodwork, which revealed normal ferritin (136), normal free T4 (1.1), moderately elevated rheumatoid factor (36), negative anti-CCP, positive pANCA (MPO and PR3 not checked) and positive IgG, but IgM was negative for parvovirus, EBV and CMV. The patient was referred to rheumatology for evaluation of possible ANCA vasculitis.

Rheumatology Presentation

Prior to her appointment, I considered how to approach the positive pANCA in the setting of constitutional symptoms, elevated ESR and CRP, mild anemia and normal creatinine. Her records did not mention pulmonary symptoms, aside from cough. She did not appear to complain of neurologic symptoms or urinary changes and had denied sinus symptoms. There was no mention of illicit drug use, unusual medications or rash. The constitutional symptoms and elevated inflammatory markers seemed a loose indication for checking ANCA, so I took the positive result with a grain of salt. This was a patient for whom a thorough history and exam would be essential.

Image 1: The chest X-ray was remarkable for apical scarring, basilar atelectasis and/or scarring, bronchiectasis in the lingula and absence of lymphadenopathy.

She walked into the clinic exam room with slow steps and appeared tired. She recounted the “strong flu-like” symptoms that had started in December and described daily fevers at 4 p.m., as well as night sweats and rigors. Her appetite had faded, leading to a loss of 20 lbs. over the course of two months. Her cheeks became fatigued with chewing food, but she thought her new set of dentures might be at fault. Weakness had become a major problem, particularly in both thighs, such that she needed to firmly hold on to the banister when ascending or descending stairs for fear of falling. She also described new difficulty raising her arms to wash her hair. She complained of severe, bilateral anterior thigh pain and posterior calf pain, also new since December. These were limiting her ability to walk—as was dyspnea; prior to December she could walk several miles at a time, and now she could only walk four blocks due to shortness of breath. Swelling had developed in both calves and both feet. Her MCPs and PIPs were painful, but had not been swollen, red or warm.

She denied recent cough, hemoptysis, chest pain, dysphagia, dry eyes or mouth, eye pain or redness, sinus symptoms or epistaxis, hearing loss, vision loss, scalp tenderness, headache, arm claudication, morning stiffness, back pain, buttock or hip pain or stiffness, rash, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dysuria, hematuria, decreased urine output and parasthesias.

Medical history included osteopenia and appendectomy. She was taking calcium and vitamin D supplements and 600 mg ibuprofen three times daily as needed for calf pain. She was born and raised in the Dominican Republic, had moved to Boston in 2011 and had a negative PPD in 2014. She was never a smoker and denied alcohol or illicit drug use, including cocaine. Her mother had died of esophageal cancer. There was no known history of autoimmune disease in the family.

The patient’s presentation raised several questions about the pathogenesis of her disease, whose answers could influence the treatment approach. Was this ILD, with an incidentally positive ANCA? … Or was this a new case of MPA with lung fibrosis & bronchiectasis?

On physical exam, she was afebrile, with normal blood pressure and oxygen saturation 99% on room air. Her weight was 20 lbs. lighter than two months prior. She appeared tired. Faint red patches were visible on the skin of her left forearm. The oropharynx had no ulcerations, and there was no conjunctival injection. Her scalp was non-tender to palpation. No cervical or supraclavicular adenopathy was palpable. Her lung exam was notable for bibasilar crackles to the mid-lung fields. The jugular venous pressure was 7 cm. The heart was tachycardic, regular, without murmur, rub or gallop. Temporal artery pulsations were full and symmetric. There were no carotid or subclavian bruits. The abdominal exam was benign. Extremity exam was notable for 2+ radial and dorsalis pedis pulses, 1+ pitting edema of the calves and feet, and extreme tenderness to palpation over the posterior calves and anterior thighs. Musculoskeletal exam revealed no synovitis and showed full range of motion in the upper and lower extremity joints. On neurologic exam, her strength was 5/5 with neck flexion and in the deltoids, symmetric 3+/5 in the triceps and biceps, 5/5 handgrip, symmetric 4/5 in the iliopsoas, quadriceps and hamstrings, and 5/5 in the anterior tibialis and gastrocnemius. Sensation was intact to light touch.

Putting the entire clinical picture together, I was most concerned for malignancy. Vasculitis seemed possible, although giant cell arteritis (GCA) seemed more consistent with her symptoms than did small vessel vasculitis. The muscle weakness was concerning for possible inflammatory myositis, but her normal transaminases placed this lower on the differential. The leg swelling and calf pain were concerning for deep vein thrombosis in the setting of an underlying inflammatory process.

At the end of the visit, a chest X-ray and further labwork were performed, and an urgent temporal artery ultrasound and Doppler ultrasound of the legs were ordered. The chest X-ray was remarkable for apical scarring, basilar atelectasis and/or scarring, bronchiectasis in the lingula and absence of lymphadenopathy (see Image 1). The radiographic differential diagnosis included interstitial lung disease (ILD), lymphoma and prior tuberculosis. Labwork revealed normal CK (34) and aldolase (5.3), urinalysis without protein and with 5 RBC, 0 WBC, and no casts, positive pANCA (MPO and PR3 pending), negative ANA, SPEP without M-spike, and elevated total IgG (3082). Doppler ultrasound of the legs was negative for deep vein thrombosis.

With the chest X-ray and these results in hand, microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) with pulmonary involvement, ILD and lymphoma were at the top of my differential.

Giant cell arteritis now seemed less likely with the pulmonary abnormalities (although underlying/undiagnosed ILD and new-onset GCA was a possibility). We referred her urgently to nephrology clinic for evaluation, scheduled a chest CT and cancelled the temporal artery ultrasound. The consulting nephrologist noted no dysmorphic RBCs or cellular casts in the urinalysis, and the spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio was normal (0.17). Based on these findings, glomerulonephritis was not suspected.

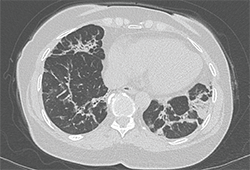

Image 2: The chest CT revealed abnormalities in the bases and lingula, with bilateral mild bronchiectasis, consolidative opacities and fibrosis.

The chest CT revealed abnormalities in the bases and lingula, with bilateral mild bronchiectasis, consolidative opacities and fibrosis (see Image 2). The appearance was concerning for cryptogenic organizing pneumonitis or resolving pneumonia, and did not have features typical of ANCA vasculitis or idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

A week after the CT scan was performed, her MPO ELISA returned highly positive (316), and PR3 was normal (1).

During a return clinic visit, her oxygen saturation dropped to 87% on room air during a six-minute walk test. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal left and right ventricular size and function, and normal pulmonary pressure.

At this point, she was clinically stable and had not received empiric corticosteroid treatment. A lung biopsy would be necessary to diagnose the underlying pulmonary process, and she was urgently referred to thoracic surgery clinic. The thoracic surgeon scheduled a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) to obtain biopsies from the right upper, middle and lower lobes. Given that the thoracic musculature would be exposed during the operative approach, he also planned to perform a serratus muscle biopsy in addition to the lung biopsies, in order to (in his words) “cover all the bases.”

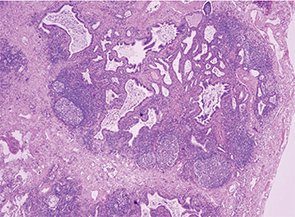

Her lung biopsy specimens captured multiple small arteries, around which was no evidence of inflammation or vessel wall necrosis. Fibrosis, bronchiectasis, germinal centers in lymphoid aggregates and bronchiolocentric inflammation were seen in the lung base and middle lobe (see Image 3). The upper lobe alveoli were relatively spared and were surrounded by chronic inflammatory infiltrates in the interstitium and pleura.

Image 3: The lung biopsy revealed fibrosis, bronchiectasis, germinal centers in lymphoid aggregates and bronchiolocentric inflammation in the lung base and middle lobe.

This patient’s case was discussed at a Pulmonary Pathology conference and was thought to be consistent with ILD, without features of vasculitis or pulmonary hemorrhage.

On the basis of constitutional symptoms, active pulmonary inflammation with B cell germinal centers, and pANCA with MPO, we decided to start treatment with both high-dose oral steroids (1 mg/kg/day) and rituximab.

Which Came First, the ILD or the ANCA?

After reviewing the lung biopsy pathology, it was time to step back and reconsider her case. The workup had been incited by a positive pANCA (later confirmed by high MPO) in the setting of constitutional symptoms, but without focal symptoms of vasculitis other than initial cough and mild dyspnea on exertion. Now, her chest imaging and lung biopsy indicated ILD with active inflammation and fibrosis, but no histologic evidence of small vessel vasculitis.

Dyspnea was a minor component of this patient’s symptoms. Her exercise tolerance had only diminished at the start of her febrile illness in December; before then, she could walk several miles. After the abnormal chest X-ray result during her first visit, the patient’s daughter called me to share that her mother had been diagnosed with a “lung problem” seven years before in the Dominican Republic, but never received treatment for it. The daughter confirmed that her mother had no difficulty breathing until the start of this most recent illness.

The patient’s presentation raised several questions about the pathogenesis of her disease, whose answers could influence the treatment approach. Was this ILD, with an incidentally positive ANCA? After all, the fibrosis on lung biopsy suggested a chronicity of many months (more than the two months during which she had felt ill), if not years. Or was this a new case of MPA with lung fibrosis and bronchiectasis, rather than the expected small artery vasculitis and capillaritis?

Several observational studies and case series have assessed the relationship of ILD and ANCA, addressing different facets of the relationship:

- How often is ILD present in patients with ANCA vasculitis? Arulkumaran et al addressed this question in a retrospective chart review of 510 patients treated for ANCA vasculitis in a nephrology clinic.1 Thirty-eight percent carried a diagnosis of MPA and 62% had granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) or eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA). Among the entire cohort, 2.7% had ILD—defined as characteristic CT scan findings and/or lung biopsy results—either at initial vasculitis presentation or later in the course of disease. All cases of ILD occurred in patients with MPA (7.2% of MPA patients); ILD was not detected in any patients with GPA or EGPA. Among MPA patients there was no survival difference based on the presence versus absence of ILD.

- How often is ANCA detected in patients with known lung disease? Among 504 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), 7.2% tested positive for ANCA (4% MPO and 3.2% PR3) at the time of first evaluation in the pulmonology clinic, in the absence of signs of vasculitis.2 Half of the patients had serial ANCA measurements, 11% of whom later developed a positive ANCA (5.7% MPO, 5.3% PR3). A clinical diagnosis of microscopic polyangiitis developed in 25% of those patients with a positive MPO-ANCA.

- What types of pulmonary pathology are seen in patients with ANCA vasculitis and pulmonary abnormalities? A case series reported pathology results among 27 patients with ANCA vasculitis (14 with MPO, 12 with PR3, one negative for both) that had undergone lung biopsy.3 Vascular lesions (78%) and interstitial abnormalities (74%) were the most common pathologic findings. Capillaritis was the most common vascular abnormality. Interstitial lesions were most frequently fibrosis, chronic inflammation, and necrotizing granulomas. Airway lesions were less common (41%) than interstitial and vascular lesions, and included bronchiolitis obliterans, necrotizing granulomas, and non-granulomatous inflammation. Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) diagnosed by radiographic or pathologic criteria was the most common finding in a series of patients with pANCA/MPO-ANCA-positive microscopic polyangiitis and lung fibrosis; in most cases, UIP preceded the diagnosis of MPA (Ulrich Specks, MD, personal communication).

In this patient’s case, we suspected that her ILD predated the onset of fevers in December, given the fibrotic component. We could not know when the ANCA had first developed, either with the initial onset of ILD or more recently. What we did know is that her fevers, weakness and calf pain greatly improved after starting high-dose oral steroids, soon followed by rituximab.

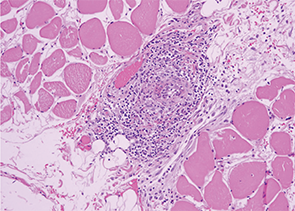

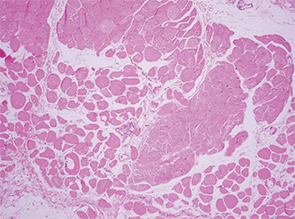

Image 4: The serratus muscle biopsy showed evidence of classic small artery vasculitis.

One week into her steroid treatment, the results of her muscle biopsy returned. Lo and behold, the thoracic surgeon-motivated serratus muscle biopsy showed evidence of classic small artery vasculitis (see Image 4)! Surrounding muscle fibers were variable in size, indicating muscle fiber atrophy secondary to ischemia in the setting of vasculitis (see Image 5). There were no inflammatory infiltrates, perifasicular atrophy or fibrosis, or degenerating or necrotic fibers to suggest inflammatory myositis.

Microscopic Polyangiitis: Unusual Manifestations

Small artery vasculitis on muscle biopsy, along with MPO-ANCA, ILD and constitutional symptoms, clinched the diagnosis of microscopic polyangiitis. Her initial symptoms seemed unusual for MPA; in particular, how were the severe calf and thigh pain part of this disease process? Birnbaum et al reported a case of MPA presenting as a “pulmonary-muscle” syndrome,4 similar to our patient. Common features between that patient and ours included pANCA with elevated MPO, normal CK and aldolase, absence of renal involvement, basilar lung fibrosis on CT chest, and small vessel arteritis identified on muscle biopsy.

Image 5: Surrounding muscle fibers were variable in size, indicating muscle fiber atrophy secondary to ischemia in the setting of vasculitis.

Calf claudication has also been reported as a presenting symptom of MPA.5 In that case report, the patient had pANCA, elevated MPO and normal PR3, normal CK and bibasilar honeycombing on CT chest. Unlike our patient, the reported case had necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis on muscle biopsy and crescentic glomerulonephritis on renal biopsy.

Summary

The patient’s fever, fatigue, calf and thigh pain, and oxygen desaturation upon walking improved days after starting high-dose steroids, followed by two doses of rituximab 1000 mg IV, two weeks apart. She continues to do well on a steroid taper and prophylactic trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Sara Tedeschi, MD, is a rheumatology fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Sara Tedeschi, MD, is a rheumatology fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Acknowledgements: The author thanks Paul Dellaripa, MD, for his assistance in caring for this patient, and Emilian Racila, MD, for the pathology slides.

Key Points

- A small percentage of patients with microscopic polyangiitis have evidence of ILD—rather than small artery vasculitis or capillaritis—on CT scan or lung biopsy.

- A similar, small percentage of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis have a positive ANCA test at some point in their disease course, and 25% of these may go on to develop microscopic polyangiitis.

- Vascular and interstitial lesions may occur with similar frequency among patients with ANCA vasculitis.

- Muscle biopsy can yield evidence of small vessel arteritis in the setting of ANCA vasculitis.

References

- Arulkumaran N, Periselneris N, Gaskin G, et al. Interstitial lung disease and ANCA-associated vasculitis: A retrospective observational cohort study. Rheumatology. 2011 Nov;50(11):2035–2043.

- Kagiyama N, Takayanagi N, Kanauchi T, et al. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive conversion and microscopic polyangiitis development in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. BMJ Open Respiratory Research. 2015 Jan 9;2(1):e000058.

- Gaudin PB, Askin FB, Falk RJ, Jennette JC. The pathologic spectrum of pulmonary lesions in patients with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies specific for anti-proteinase 3 and anti-myeloperoxidase. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995 Jul;104(1):7–16.

- Birnbaum J, Danoff S, Askin FB, Stone JH. Microscopic polyangiitis presenting as a ‘pulmonary-muscle’ syndrome: Is subclinical alveolar hemorrhage the mechanism of pulmonary fibrosis? Arthritis Rheum. 2007 Jun;56(6):2065–2071.

- Kim MY, Bae SY, Lee M, et al. A case of ANCA-associated vasculitis presenting with calf claudication. Rheumatol Int. 2012 Sep;32(9):2909–2012.