COVID-19 causes myriad cardiac dysfunctions, ranging from mild to fulminant disease, including myocarditis, acute congestive heart failure, cardiogenic shock and sudden cardiac death.1,2 COVID-19 myocarditis can mimic cardiac sarcoidosis clinically and on cardiac imaging, which can lead to diagnostic challenges and treatment delays.

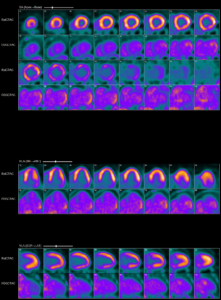

We present a case of cardiac sarcoidosis with interval development of metabolic activity on cardiac positron emission tomography (PET)/computerized tomography (CT) scan following SARS-CoV-2 infection in a patient whose disease had been stable on a chronic immunosuppressive regimen, with resolution of active sarcoidosis on cardiac imaging prior to the infection.

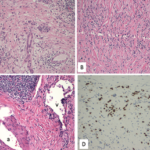

Abnormal myocardial 18FDG uptake on PET/CT nuclear scan is highly suggestive of active

myocardial inflammation involving basal anterior wall, mid to basal anterolateral wall and basal lateral and inferolateral regions. (Click to enlarge.)

The Case

A 60-year-old white man with a past medical history of nephrolithiasis and hyperlipidemia presented with three days of nausea, vomiting, chest discomfort, palpitations and dyspnea. On presentation, he was tachycardic, with a heart rate of 250 and euvolemic on examination. An electrocardiogram was consistent with ventricular tachycardia, for which he was defibrillated.

Initial blood work showed elevated B-type natriuretic peptide (1,058 pg/mL; reference range [RR]: 0–99 pg/mL) and troponin that peaked at 3.4 ng/mL (RR: 0–0.045 ng/mL). A chest X-ray showed a prominent cardiac silhouette without pulmonary edema or active lung disease. CT chest angiography was negative for pulmonary embolism and showed mild cardiomegaly. An echocardiogram (ECHO) revealed a new diagnosis of grade 2 diastolic and moderate systolic heart failure with ejection fraction (EF) of 25–30%. Left heart catheterization was negative for coronary artery disease, and he underwent cardioverter defibrillator implantation for secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death.

An evaluation for non-ischemic cardiomyopathy was sought, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed transmural, late, gadolinium enhancement within the basal lateral wall, consistent with a clinical diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. Guideline-directed medical therapy was initiated, and he was discharged.

His initial cardiac PET scan on follow-up after discharge was negative and improvement in EF to 35–40% was noted on the echocardiogram. Thus, immunosuppressives were not initiated.

A year later, he developed worsening fatigue for which a cardiac PET scan was repeated. It showed active cardiac sarcoidosis with minimal metabolic activity within basal lateral and inferolateral segments of the left ventricle. Immunosuppressive therapy with prednisone taper and 1 g of mycophenolate daily was initiated.