COVID-19 causes myriad cardiac dysfunctions, ranging from mild to fulminant disease, including myocarditis, acute congestive heart failure, cardiogenic shock and sudden cardiac death.1,2 COVID-19 myocarditis can mimic cardiac sarcoidosis clinically and on cardiac imaging, which can lead to diagnostic challenges and treatment delays.

We present a case of cardiac sarcoidosis with interval development of metabolic activity on cardiac positron emission tomography (PET)/computerized tomography (CT) scan following SARS-CoV-2 infection in a patient whose disease had been stable on a chronic immunosuppressive regimen, with resolution of active sarcoidosis on cardiac imaging prior to the infection.

Abnormal myocardial 18FDG uptake on PET/CT nuclear scan is highly suggestive of active

myocardial inflammation involving basal anterior wall, mid to basal anterolateral wall and basal lateral and inferolateral regions. (Click to enlarge.)

The Case

A 60-year-old white man with a past medical history of nephrolithiasis and hyperlipidemia presented with three days of nausea, vomiting, chest discomfort, palpitations and dyspnea. On presentation, he was tachycardic, with a heart rate of 250 and euvolemic on examination. An electrocardiogram was consistent with ventricular tachycardia, for which he was defibrillated.

Initial blood work showed elevated B-type natriuretic peptide (1,058 pg/mL; reference range [RR]: 0–99 pg/mL) and troponin that peaked at 3.4 ng/mL (RR: 0–0.045 ng/mL). A chest X-ray showed a prominent cardiac silhouette without pulmonary edema or active lung disease. CT chest angiography was negative for pulmonary embolism and showed mild cardiomegaly. An echocardiogram (ECHO) revealed a new diagnosis of grade 2 diastolic and moderate systolic heart failure with ejection fraction (EF) of 25–30%. Left heart catheterization was negative for coronary artery disease, and he underwent cardioverter defibrillator implantation for secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death.

An evaluation for non-ischemic cardiomyopathy was sought, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed transmural, late, gadolinium enhancement within the basal lateral wall, consistent with a clinical diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. Guideline-directed medical therapy was initiated, and he was discharged.

His initial cardiac PET scan on follow-up after discharge was negative and improvement in EF to 35–40% was noted on the echocardiogram. Thus, immunosuppressives were not initiated.

A year later, he developed worsening fatigue for which a cardiac PET scan was repeated. It showed active cardiac sarcoidosis with minimal metabolic activity within basal lateral and inferolateral segments of the left ventricle. Immunosuppressive therapy with prednisone taper and 1 g of mycophenolate daily was initiated.

A follow-up cardiac PET scan six months later showed complete resolution of active cardiac sarcoidosis, with improvement in EF to 40–45% on echocardiogram. Prednisone was weaned.

The patient developed a COVID-19 infection a few months later that did not require hospitalization.

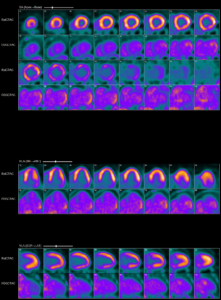

A surveillance cardiac PET/CT scan four months after the infection showed interval development of metabolic activity within the basal anterior wall, mid to basal anterolateral wall, basal lateral and inferolateral regions, suggesting active cardiac sarcoidosis without evidence of extracardiac sarcoidosis. An echocardiogram showed worsening EF of 30–35%, with regional wall motion abnormalities and severely hypokinetic basal segments of the anterior and anterolateral walls.

He was restarted on prednisone taper, and mycophenolate was increased from 2 g daily to 3 g daily. His follow-up PET/CT scan showed no evidence of cardiac or extracardiac

sarcoidosis, and an echocardiogram showed improved EF of 40–45%.

Discussion

Mechanisms of COVID-19 mediated myocarditis include direct viral injury, systemic inflammation causing cytokine storm, stress-induced cardiomyopathy and microvascular thrombosis that can be focal or diffuse.1,2,5 Myocardial injury is most often seen later in the disease course, sometimes occurring several days after initial symptoms.

This image shows increased cardiac 18FDG uptake on the PET/CT nuclear scan without evidence of extracardiac inflammatory changes. (Click to enlarge.)

Even those who have clinically recovered from COVID-19 can have subclinical myocarditis. Depending on the extent of myocardial damage and time course of the disease, cardiac MRI abnormalities include diffuse myocardial edema, seen as regional or global hyperintensity; hyperemia, as evidenced by early gadolinium enhancement; and fibrosis, seen as a foci of late gadolinium enhancement.4-6 These findings depend on the extent of myocardial damage and time course of the infection. Similar imaging findings are seen in cardiac sarcoidosis, which has a high rate of recurrence with prednisone tapering.

It remains unclear whether the myocardial uptake seen on the PET/CT scan in our case was secondary to COVID-19 myocarditis vs. cardiac sarcoidosis, or whether COVID-19 plays a role in inducing the inflammatory process of sarcoidosis, although given the similar distribution of involvement with this patient’s prior cardiac sarcoidosis flares, one of the latter two scenarios seems more likely. Data on COVID-19 in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis are scarce, and further research is required to better understand the cardiac sequalae of this infection, as well as the effects of immunosuppressive therapies in these patients (see Figures 1 and 2).3

Simranjit Kaur, MBBS, is a third-year internal medicine resident at MedStar Georgetown—Washington Hospital Center, Washington, D.C., and will be pursuing rheumatology fellowship at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C. after her residency.

Simranjit Kaur, MBBS, is a third-year internal medicine resident at MedStar Georgetown—Washington Hospital Center, Washington, D.C., and will be pursuing rheumatology fellowship at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C. after her residency.

Sirajum Munira, MD, is an attending rheumatologist affiliated with the Annapolis Rheumatology group, Maryland.

Sirajum Munira, MD, is an attending rheumatologist affiliated with the Annapolis Rheumatology group, Maryland.

Farooq H. Sheikh, MD, FACC, is an attending physician at MedStar Heart Institute at Washington Hospital Center, Washington, D.C., where he also serves as the medical director of the Advanced Heart Failure Program and regional director of the MedStar Infiltrative Cardiomyopathy Program. He specializes in heart failure and cardiac transplantation.

Farooq H. Sheikh, MD, FACC, is an attending physician at MedStar Heart Institute at Washington Hospital Center, Washington, D.C., where he also serves as the medical director of the Advanced Heart Failure Program and regional director of the MedStar Infiltrative Cardiomyopathy Program. He specializes in heart failure and cardiac transplantation.

Anjani Pillarisetty, MD, RhMSUS, is an attending physician and certified musculoskeletal ultrasound rheumatologist at MedStar Georgetown—Washington Hospital Center, Washington, D.C., where she also serves as the associate program director in the Division of Rheumatology.

Anjani Pillarisetty, MD, RhMSUS, is an attending physician and certified musculoskeletal ultrasound rheumatologist at MedStar Georgetown—Washington Hospital Center, Washington, D.C., where she also serves as the associate program director in the Division of Rheumatology.

References

- Liu J, Deswal A, Khalid U. COVID-19 myocarditis and long-term heart failure sequelae. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2021 Mar 1;36(2):234–240.

- Agdamag ACC, Edmiston JB, Charpentier V, et al. Update on COVID-19 myocarditis. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020 Dec 9;56(12):678.

- Manansala M, Ascoli C, Alburquerque AG, et al. Case series: COVID-19 in African American patients with sarcoidosis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020 Nov 4;7588527.

- Huang L, Zhao P, Tang D, et al. Cardiac involvement in patients recovered from COVID-2019 identified using magnetic resonance imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020 Nov;13(11):2330–2339.

- Sanghvi SK, Schwarzman LS, Nazir NT. Cardiac MRI and myocardial injury in COVID-19: Diagnosis, risk stratification and prognosis. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021 Jan 15:11(1):130.

- Shah S, Danda D, Kavadichanda C, et al. Autoimmune and rheumatic musculoskeletal diseases as a consequence of SARS-CoV-2 infection and its treatment. Rheumatol Int. 2020 Oct:40(10):1539–1554.