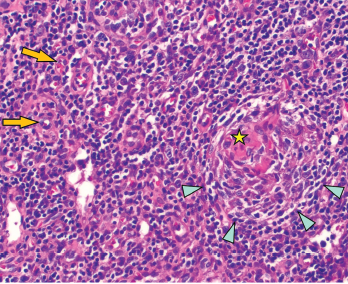

Figure 2: Regressed germinal center with follicular dendritic cell prominence (star), onion-skinning (blue arrowhead) and increased vascularity (orange arrows) are seen.

On exam, the patient was febrile, hypotensive and tachycardic. She did not have any eye inflammation, oral or nasal ulcers, abnormal cardiac or pulmonary exam, skin rash or synovitis. There was subcentimeter axillary lymphadenopathy, but no cervical or inguinal lymphadenopathy. A neurologic exam was limited due to sedation, but rightward gaze deviation was noted initially on arrival.

Laboratory values showed pancytopenia, with a white blood cell count of 1.0 x109/L (RR: 3.2–9.8 x109/L), hemoglobin 7 g/dL, platelet 10×109/L (RR: 3.2–9.8×109/L), creatinine 2 mg/dL (RR: 0.4–1.0 mg/dL), AST 200 U/mL (RR: 15–40 U/L), ALT 600 U/mL (RR: 14–50 U/L), ESR 30 mm/hour, CRP 8 mg/dL, ferritin >15,000 ng/mL, triglycerides 500 mg/dL (RR: <500 mg/dL), lactate dehydrogenase 4,000 U/L (RR: 100–200 U/L), sIL-2R 8,000 U/mL (RR: <1,100 U/mL), and absent NK cell activity. CSF studies were normal.

Computed tomography (CT) of the brain was normal. CT of the chest and abdomen revealed bulky lymphadenopathy.

An excisional biopsy of an axillary lymph node showed regressed germinal centers (see Figure 1), hyalinized vascular proliferation (see Figure 2) and mild to moderate plasmacytosis. No hemophagocytosis was noted on the biopsy, staining for HHV-8 was negative, and there were no CD4-/CD8 T cells.

The biopsy was interpreted as angiofollicular lymphoid hyperplasia. Given the pathologist’s comment regarding the Castleman-like features, additional serum laboratory tests, including vascular endothelial growth factor, serum protein electrophoresis, human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were sent and were unrevealing.

Initially, the working diagnosis was Castleman-like disease secondary to SLE. The patient was managed for macrophage activation syndrome with high-dose corticosteroids and 100 mg of anakinra every six hours, but she was not improving.

Her hospitalization was complicated by oral herpes simplex virus ulcers and Klebsiella bacteremia, which initially limited the choice of additional immunosuppression beyond corticosteroids and anakinra.

Given her lack of response to treatment and the absence of lupus-specific autoantibodies, a multidisciplinary discussion with a hematologist and a pathologist was held. The pivotal question involved whether she had Castleman-like disease secondary to SLE, a key exclusion criterion for idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease (iMCD)—or whether she had primary iMCD.

Diagnosis

Although our patient’s clinical features included fever, hemolytic anemia, altered mental status and diffuse pain, none of these features are specific to SLE. Her renal involvement had included proteinuria; however, she had no significant active urinary sediment, and there was no classic immune complex glomerulonephritis seen on renal biopsy—only podocyte effacement was noted. Nevertheless, her ANA positivity and hypocomplementemia had led providers to favor the diagnosis of SLE during previous evaluations.

Ultimately, we concluded her underlying disease was more consistent with iMCD rather than Castleman-like disease secondary to SLE. She was subsequently given 11 mg/kg of siltuximab, and anakinra was stopped. Following administration of siltuximab, her pancytopenia and inflammatory markers all improved, and we were able to taper corticosteroids.

Our plan was for the patient to receive 11 mg/kg of siltuximab every three weeks; however, she did not follow up after discharge and, ultimately, was lost to care.